How the science of jet lag is elevating the travel experience

Airlines and apps are using the latest sleep and circadian neuroscience to revolutionise how long-haul travellers handle jet lag. From sleep cycles to diet and light exposure, here’s what you can do when transitioning to a new timezone

It’s been 20 years since the release of Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation, a film that saw the paths of Scarlett Johanssen and Bill Murray’s characters – both jaded by jet lag – converge in the early hours at the Park Hyatt Tokyo. For frequent flyers, it reflected familiar shades of their own travel experiences, whether wide awake late at night, nodding off nose-first at breakfast meetings, or listlessly floating through duty-free on a layover. Despite its relatability, the decades since have seen little advance in our understanding of jet lag and its causes – a phenomenon that can hamstring even the most seasoned traveller.

Generic advice that many will be familiar with has tended to circulate around staying hydrated and limbering up for a jog on either end of a long-haul flight. Others advise certain diets, acupuncture, or sinking a melatonin or two to knock you out after takeoff. Or splashing out for business class and banking sleep in comfier surrounds. However, recent breakthroughs within the field of circadian science are enhancing our collective understanding of the causes and effects of jet lag – and therefore how best to combat it – offering the potential to revolutionise our experience of travel.

What is circadian science?

It was in 2017 that three scientists won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with their breakthrough studies explaining how plants, animals and humans adapt their biological rhythm so that it synchronises with the revolution of the Earth. This, taken together with scores of subsequent studies on the topic, is helping unlock our understanding of circadian science and, subsequently, jet lag.

“Light is the key ‘Zeitgeber’, or ‘time giver’, that connects the timing of our internal rhythm with the light-dark cycle of the sun,” says British sleep scientist Dr Sophie Bostock. We’re programmed to wake and sleep according to these “circadian” rhythms, and jet lag is caused by temporary disruption of these internal rhythms when we travel to different time zones. This can make us feel disoriented or unwell. “Operating at odds to this rhythm puts stress on the body. We can absolutely do it, but it comes at a physiological cost,” adds Bostock, pointing to research that highlights the negative health implications for shift workers or flight crews who fly without sufficient recovery time.

Australian airline Qantas claims to be getting closer to conquering jet lag. Working in conjunction with the University of Sydney’s Charles Perkins Centre, the airline ran passenger trials in 2019 on three hefty long-haul trial flights between Sydney and New York and London, during which passengers wore biometric monitors. The flights, set to launch in late 2025, will be the longest nonstop flights in the world, each around the 20-hour mark.

The study found that adjusting cabin lighting to reflect the destination time zone, encouraging stretch and movement activities in an onboard wellness area, and aligning meal services to each traveller’s body clock resulted in passengers suffering less severe jet lag, and benefitting from better inflight sleep quality and cognitive performance in the days immediately following their flight. To send passengers to sleep, Quantas served dishes rich in tryptophan, an amino acid linked to sleepiness, including dairy, bread and chicken.

Peter Cistulli, professor of sleep medicine at the University of Sydney, advises that although research is ongoing, there are signs that these interventions reduced the impact of ultra long-haul travel. “We are optimistic that we can make a real difference to the health and wellbeing of international travellers through this partnership with Qantas,” he says.

Appliance of science and jet lag apps

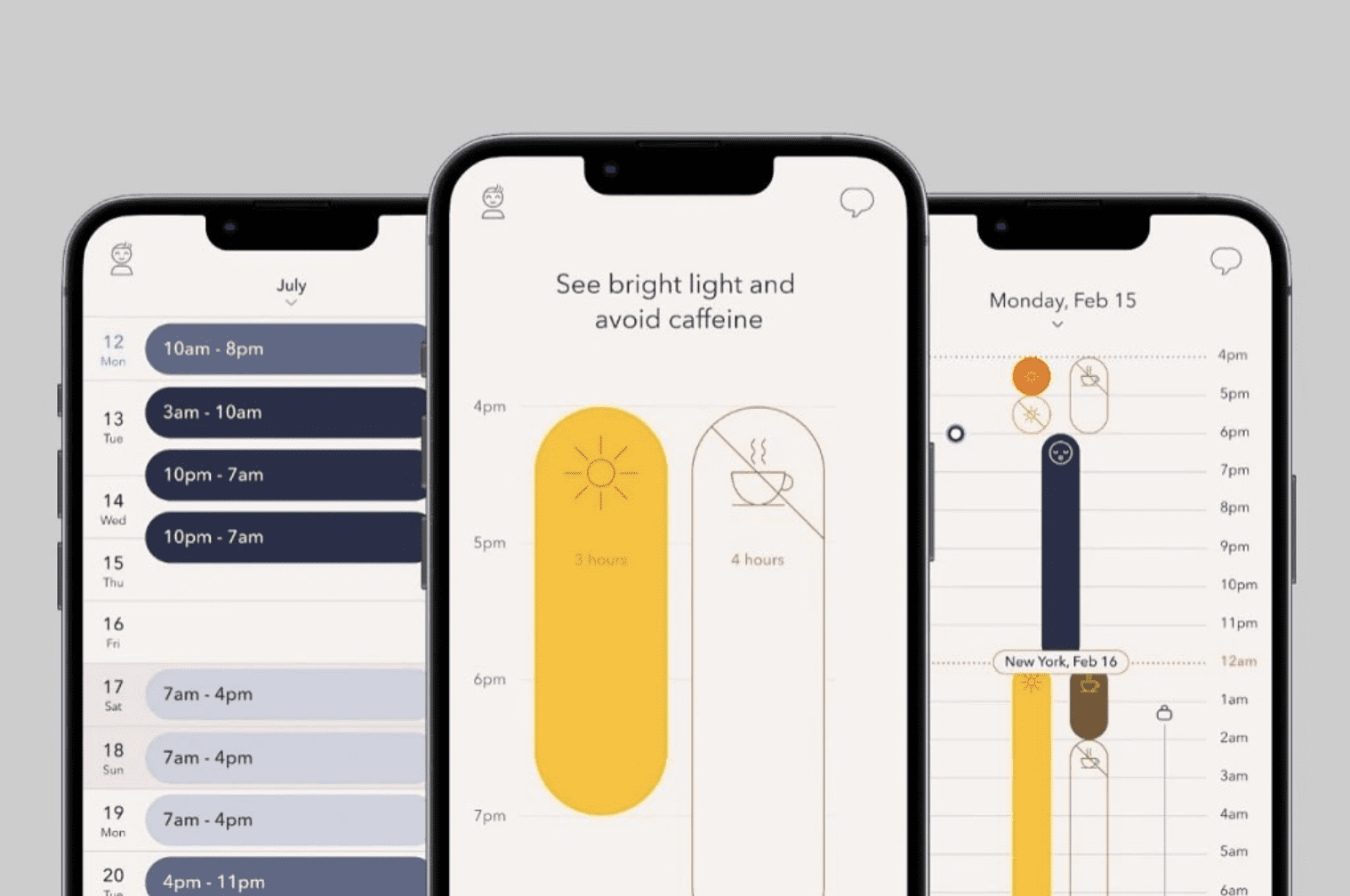

These findings come as little surprise to Mickey Beyer-Clausen, the co-founder and CEO of Timeshifter, an app informed by circadian science. His co-founder, Harvard Medical School associate professor Dr Steven W Lockley, has worked with Nasa on sleep-cycle plans for astronauts since 2010. Timeshifter, which launched in 2018, uses the latest circadian, lighting, caffeine and melatonin science within an algorithm designed to help your body clock adjust to a new timezone.

Travellers enter their flight details into the app and Timeshifter generates a personalised jet lag ‘plan’ based on circadian science. Users can tweak their circadian clock by adjusting their sleep pattern ahead, during and after a flight, aided by the optional scheduled use of melatonin or caffeine.

“People are more interested in sleep than they were ten years ago,” says Beyer-Clausen, citing collaborations with United Airlines and global hotel chains such as the Six Senses group. “Circadian science as a field is still not really understood by many. People talk about a ‘circadian rhythm’, but actually it should be plural: we have circadian clocks in all of our functions, everything from your organs to your metabolism, bones and skin function.” A big believer in the potential of the field, he adds that its influence goes beyond long-haul travellers, from helping shift workers to the timing of medical treatments. He predicts it is set to explode as soon as the development of better wearable tech catches up.

Many confuse jet lag with health and wellness

Debunking jet lag myths

Timeshifter is currently the world’s most downloaded jet lag app, although a swathe of new services are starting to emerge that take a similar approach to solving jet lag – something Beyer-Clausen sees as inevitable. Yet his main frustration is with the proliferation of what he calls “jet lag myths” or gimmicks that muddy the water. “Many confuse jet lag with health and wellness, but let’s divide the two: there are things you do for health and wellness and things you do for jet lag,” he says. “Being hydrated, for example, does not impact jet lag at all but, of course, it’s definitely worth staying hydrated anyway because that’s good for your health.”

Instead, he continues, it’s the timing of light exposure that’s key – something that can be hacked during your flight if necessary by jacking up the brightness of your in-flight entertainment system or wearing dark sunglasses according to needs. He advises that individually tailored plans are essential as everyone’s internal rhythms are different. “You need a personalised approach – anything generic should be ignored” he says. “If you sleep at the wrong time – at a time when you should be prioritising bright light – you’re shifting away from your new time zone, making jet lag worse. If you’ve just paid £6,000 for a business-class flight, it makes no sense.” The same approach applies to meal times: eating a big meal when it’s biological night in your body – such as eating at your destination when it’s 3am in your own time zone – can cause a huge glucose response, similar to that experienced by people with diabetes.

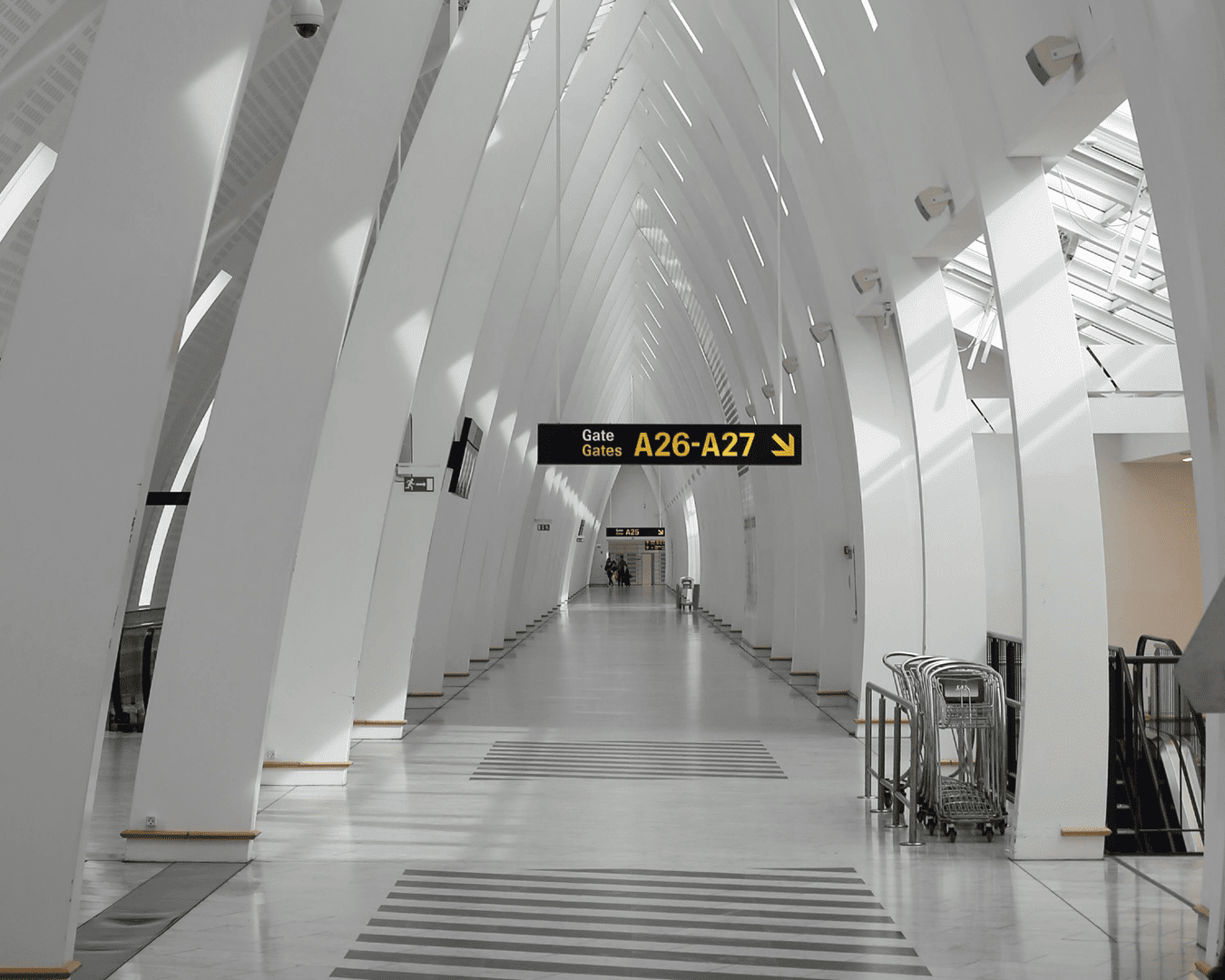

Airport design

Airlines have begun adapting terminals and lounges to aid weary travellers in transit, including the Daylight Booster Zone in Copenhagen’s SAS Lounge, Qantas’s alfresco barbecue deck, and KLM’s 110-metre LED light wall at Schiphol, which is designed to simulate the Dutch sky outside – all signs that the concept of circadian science is catching on. “Over the next few years we’ll see a significant improvement in how we treat jet lag,” says Beyer-Clausen, adding that the development of biological lighting, which can mimic day and night to match the needs of human biological cycles, is likely to become far more common in airport lounges. “If you’re an airline or a hotel and you’re not taking this seriously yet then you’re in trouble, because companies are starting to do all kinds of experiments, and it’ll become a big differentiator between products.”

However, it may be a few years before airport design catches up with the science. “We do accommodate a quiet area in all of our lounges,” says David Loyola, design director at aviation architects Gensler, pointing to their work for Copa Airlines in Panama, which has quiet rooms, low lighting and acoustic wall panels. “We haven’t really addressed circadian rhythms yet. It’s an interesting conversation, but those in transit are only a small demographic of people who use the lounge. As an operator, it’s a challenge: they don’t want people sleeping with their feet up on seats as it takes up space, and can impact the passenger experience.” Designing for different airport users like workers and passengers from differing time zones makes adequate provision of circadian-effective lighting complicated – for now.

How to beat jet lag

Until then, Bostock suggests a simple plan for those with a long-haul flight on the horizon. “In brief – and perhaps most importantly – fly well rested,” she says. “Bank sleep in advance if you can. Start to adjust to your new time zone a few nights before you go if feasible and use Timeshifter or Jet Lag Rooster to guide your light exposure.”

As we get wiser to jet lag and its causes, the potential exists for future travel to be a far smoother, more productive experience. “What I’ve discovered is a newfound appreciation for travel,” says Beyer-Clausen. “Rather than flying in, going to a hotel, getting room service and having a club sandwich in bed watching CNN, I can now go out to a restaurant the night I arrive and enjoy that destination more.”