Overtourism on the continent: Europe’s problems and solutions

Following a summer of heatwaves, disrupted holidays, and visitor numbers reaching pre-pandemic highs in some parts of Europe, how is the continent tackling overtourism and protecting local communities?

For many, summer 2023 was the one that got too hot to handle, from devastating wildlifes in Hawaii to Canada experiencing its worst wildlife season on record. It was the same for much of southern Europe, as wildfires raged across Greece, Turkey, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Cyprus, and Croatia. This didn’t stop droves of tourists descending on popular cities, leading to near unmanageable visitor numbers and pressure on resources. Crowds backed up on bridges to visit Venice’s St Mark’s Square, while there were reportedly two-hour queues to see the Acropolis in Athens.

According to the European Travel Commission’s Trends and Prospects report (May-July 2023), Europe is almost back to 2019’s pre-pandemic tourist arrivals, with the greatest number arriving from the US. In the first quarter of 2023, 426 million nights were spent in tourist accommodation in the EU – 28 per cent more than the same period in 2022 – with Lisbon, Dubrovnik, Rome, Milan, Barcelona and Athens among the most popular destinations. It is not solely the number of tourists that pose a problem, but often travellers’ behaviour and how the city is built to support droves of visitors. Croatia’s 2023 Respect the City promotional campaign includes an animated video advising on behavioural best practices, including refraining wheeling suitcases along cobbled streets and dressing appropriately.

What is overtourism?

But how much is ‘too much’ and what exactly is overtourism? Are there solutions and are they working? As is usually the case, polarising the debate isn’t the answer when the problem itself is nuanced. As Tim Fairhurst, Secretary General of ETOA, the trade association for better tourism in Europe, puts it, ‘There’s a risk of framing the debate in oppositional terms, which might impede progress. ‘Fight against overtourism’ is a common phrase, but can quickly slide into ‘anti-tourism’, thus anti-tourist sentiment; dangerous territory.”

As Fairhurst explains: the issue isn’t necessarily the actual tourism (although in some places, it is), but often, how the business of tourism is managed, and how it does, or doesn’t, affect the people who actually live there. “It’s a management problem – usually exacerbated by politics – not a war,” he adds. “What works for residents often also works for visitors.”

The impact of overtourism

For locals in popular tourist destinations, overtourism can impact life in several ways, including housing supply, traffic, litter and pollution. Take Lisbon as one example, where rising rents and property prices have made it unaffordable for many local people, who are pushed to move out of the centre. The city’s mayor rebuffed this claim, advising that the city is “far from overtourism,” and has backed increasing the tourist tax (currently priced at 2 EUR a night) to pay for services such as cleaning of public spaces including parks and streets. But this demonstrates one of the main complications of the issue: when some residents experience one aspect, and businesses another.

“It’s exasperating to have so many people in one place if it interferes with daily life,” says Fairhurst. “Take the Lake District in the UK, where traffic is one of the biggest concerns. If you’re a local tradesperson hopping between towns to get to your next job and it takes two hours to travel ten miles, that’s hugely disruptive.”

Airbnb is often at the centre of accusations around the rise in private rental properties, resulting in long-term residents being priced out of. “The solution to overtourism lies in dispersal,” an Airbnb spokesperson told me. “While hotels continue to concentrate tourists in historic hotspots, listings on Airbnb are more dispersed than ever.” Airbnb hopes to counteract mass tourism by investing in technologies that are diverting bookings away from Europe’s most saturated tourist hotspots in support of more sustainable travel trends.” One example is a partnership between Airbnb and the Association of Rural Mayors of France to boost short-term rental accommodation in villages, tapping into the heritage tourism potential of the French countryside.

Data from Eurostat – the EU’s statistical office that Airbnb, Booking.com, Expedia Group and TripAdvisor all share data with – shows that Airbnb guests account for a smaller proportion of overall visitor numbers to Europe’s major cities, compared to guests using hotels and other accommodation types. For example, Airbnb only accounts for four per cent of visitors to Venice, and five per cent in Amsterdam. However, if the four or five per cent of rentals are concentrated in certain areas, it can and does pose problems, and the reality is that some cities, and some neighbourhoods, will experience different issues more keenly.

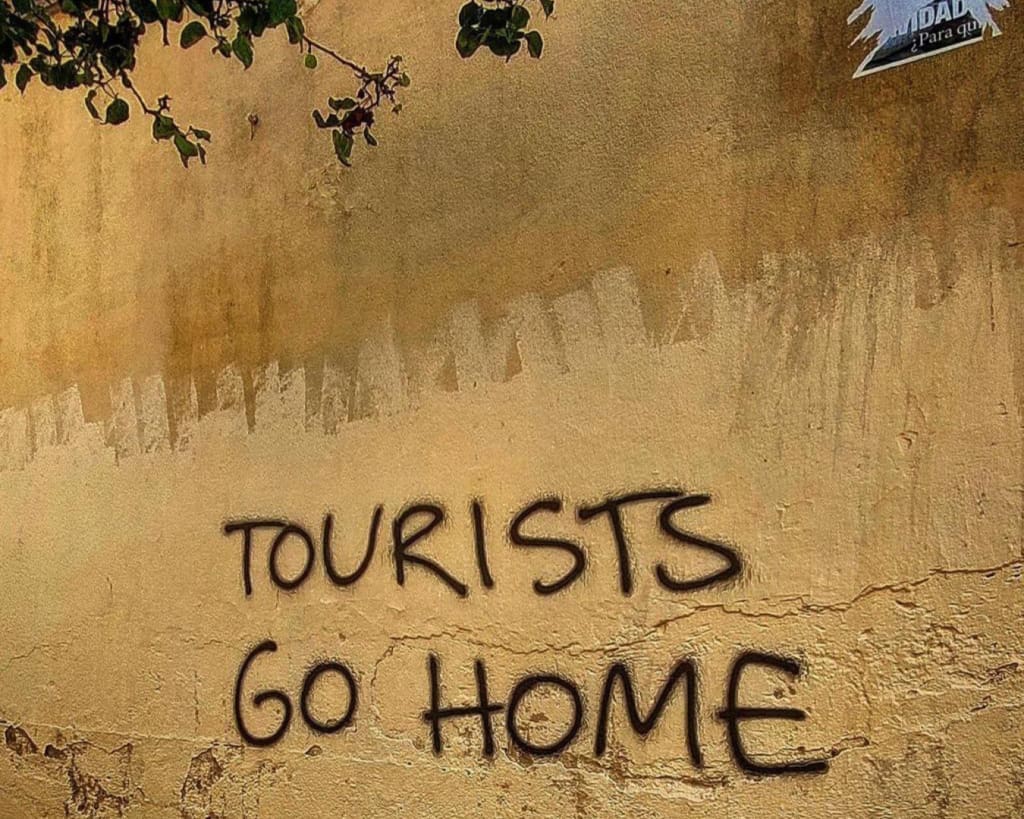

In Barcelona, ‘Tourists Go Home’ and ‘Tourism Kills Neighbourhoods’ signs have been a frequent sighting. Ada Colau, who served as Barcelona mayor from 2015 to 2023, told Reuters: “We like tourism, but overcrowding triggers problems of mobility, speculation and gentrification that put our local way of life at risk. Therefore, we have to regulate it.” Colau implemented a number of strategies to control the flow of tourists to the city, including limiting the number of available hotel beds and restricting new hotels from opening in the historic centre. Meanwhile, locals can enjoy free access to Park Güell and other attractions.

Other times, we can ‘feel’ overtourism when we have an aversion to certain behaviours, as opposed to practical obstacles being the issue. “Take a town that wants to impose a visitor limit,” says Fairhurst. “Sometimes what’s actually motivating their decision is an almost anthropological reaction to some fellow humans behaving in a certain way, such as taking non-stop photos, or not respecting a dress code in a church.”

But as Fairhurst advises, polarising the debate does it no favours. “Tourism is neither all good nor all bad, just as a single tourist may be self-absorbed or altruistic,” he says. “This is also where the tourism industry can play a role to communicate better, such as educating visitors on cultural etiquette, and encouraging them to be public transport-literate.”

Solutions to overtourism

Destination management strategies vary from capping visitor numbers, introducing tourist taxes, restricting opening times and access, pre-booking popular attractions, and promoting lesser-known places. However, this can often cause the problem to simply move elsewhere. Venice redirected cruise ships to the industrial zone of Marghera but that’s still within the lagoon. Barcelona, Europe’s worst cruise port for air pollution, is currently looking at alternative ways to significantly reduce cruise ship numbers.

Another strategy is marketing the ‘shoulder season’ by extending the traditional ‘peak’ season from March to November where the infrastructure permits. Not only does this spread numbers, it’s better for some travellers: for hiking, city breaks and active holidays, pre-and post-summer are optimum times.

Italy has been experiencing a significant increase in visitors, but for the past eight years, ENIT (the Italian Government Tourist Board) has been actively promoting slow tourism via public transport where possible to smaller, lesser visited destinations, such as to Italy’s Most Beautiful Villages, to reduce stress on hotspots such as Rome, Florence, Venice and the Cinque Terre.

“To combat overtourism, some local authorities such as Venice are looking to introduce a city entry tax” says Flavio Zappacosta, head of UK and Ireland at ENIT (Italian Government Tourist Board). Venice, considered by many as a byword for overtourism, is set to introduce an admission fee in 2024 of 5 EUR per adult to be trialled during peak holiday periods. Venice tourism councillor Simone Venturini has advised that the fee is not a money-making incentive, and is designed instead to balance the flow of tourists visiting its historic canals, and find a balance between residents and visitors. It remains to be seen if a low-priced tax will discourage visitors, as 80 per cent of Venice’s visitors come just for the day.

“Other possible measures include limiting the number of visitors in areas with a more fragile natural environment such as Cinque Terre in Liguria,” Zappacosta adds, “as well as restricting holiday flat rentals in the centre of big cities to help reduce overtourism and the alienation of local inhabitants.”

The solutions are rarely simple, especially when business is involved, as Eleni Skarveli, director of the Greek National Tourist Office (GNTO), UK & Ireland, knows: “Santorini witnesses a surge in tourist numbers seeking Instagrammable sunset snapshots in Oia, particularly during July and August,” she tells me. “In 2018, attempts were made to introduce a cap of 8,000 daily cruise visitors, but this approach faced resistance within the local community, revealing the complexities of handling overtourism.”

Balancing differing local concerns and tourism infrastructure with sustainable travel practices is a constant challenge for most destinations. The onus seems to be on governments, tourism officials and travel companies to think carefully about what a town or resort needs so that tourism is a positive factor. While it is a source of income for many people and a thriving industry, it shouldn’t deprive residents of quality of life, housing, and other facilities.

“It’s vital that sustainability is supported at government and policy level,” says Manuel Butler, director of the Spanish Tourist Office (UK). As an example, the Spanish Government has approved a new 3.4 billion EUR initiative, the ‘Next Generation’ funds, for the transformation and modernisation of Spanish tourism, with 1.9 billion EUR supporting local and regional destinations with sustainable initiatives.

Butler also cites tourism and eco taxes as a way to control numbers and raise funds that can go back into the city. The Balearic Islands launched its tourism tax (between 1 EUR and 4 EUR a day, depending on the accommodation category) in 2016, funding 168 projects focused on the long-term preservation and sustainability of the archipelago, including supporting farmers and forest restoration, improving welfare of hospitality workers, and restoring historic architecture. “The tax is higher in summer months and lower in the winter,” adds Butler. Regions such as Cataluña also operate tourist taxes and an entry free for Valencia is currently being discussed.

“Improvements to Spain’s train network (RENFE) is also part of the solution, making it easier to reach lesser-visited destinations with public transport. Spain is also one of many European countries that have launched digital nomad visas to non-EU residents to encourage longer stays. While the pros and cons of digital nomads is often debated – again, raising issues such as housing availability and city infrastructure – when successful, it boosts local economy and avoids short-term rentals.

What next?

A full reassessment of the destination, followed by strategic, smart, long-term thinking instead of short-term fixes is one way. Does a city need another hotel? What’s the ideal balance of visitors and tourists? Do travellers want to visit a ‘model village’ historic old quarter with no sense of community, where every other building is a hotel, souvenir shop or restaurant, or do they want to visit a living, breathing Old Town?

Rural tourism, second cities and smaller towns, and mountain and lakes tourism are just some examples of alternatives to popular urban centres, beaches and resorts which require more or better investment and communication of these places.

“Collaboration is key to increase the chance of success. There’s clear evidence that if you involve a variety of people in decisions – not just those with the loudest voices and the time to use them – there’s stronger support,” says ETOA’s Tim Fairhurst. “We also need to think about the ‘how we do it’ better. For example, we can flatten out behaviour by asking accommodations to offer flexibility on changeover days so one destination doesn’t have predominantly Friday-to-Friday arrivals and departures. There are so many unexplored opportunities to optimise capacity and manage visitor flow if we give the travel industry time to make the changes.”