The daring creatives who shaped modern Mumbai

Bandana Tewari shares an ode to her home in Mumbai, which played host to a cast of designers, DJs, musicians and writers, who came together to transform the creative energy of the city and raise the profile of Indian artisanship across the world.

Circa 2000 was an electric time in Bombay. Yes, Bombay. Amongst us, the fiery stakeholders of a cantankerous, bawdy and belligerent megacity, the renaming of Bombay to Mumbai (which occurred in 1995) still sat awkwardly in our psyche, like teenagers sitting uncomfortably with their passage into adulthood. Mumbai – named after the patron goddess of the city Mumbadevi – became the cynosure of change, cultural sovereignty and dollops of swag that heralded a feisty young India. Were we, the newly minted misfits, the proverbial round pegs in a square hole, ready for it?

I lived on the ground floor of a towering faux French house on the edge of the Arabian Sea. It was called Champagne House, Number 69 (the name set a precedent for what was to come). It had a particularly long corridor, speckled with sunlight, leading to dramatic bay windows overlooking a glorious sea that we dared not dip our toes into. The rats – crawling amidst the reclaimed rocks strewn on the beach – were bigger than cats. Bombay was just that: a medley of the sacred and the profane in a lewd mix.

But if you peeked into my home, you’d find a fertile breeding ground for creative mavericks from different Indian states or overseas, finding their feet in Mumbai. This city was our desi New York. In the midst of this cultural bric-a-brac of people and things, Champagne House was the landing strip for the zeitgeist.

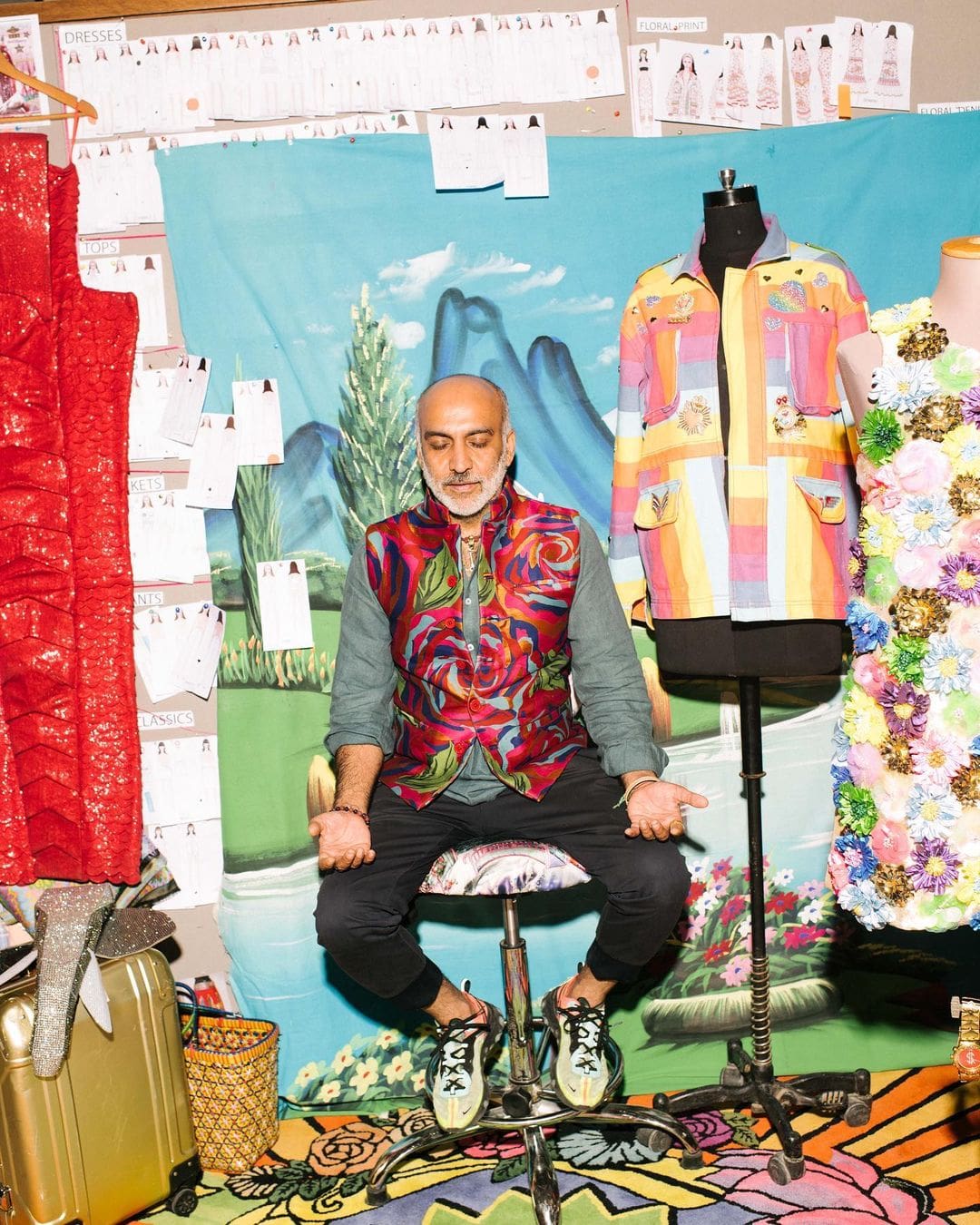

I was surrounded by rule-breakers. Manish Arora, the enfant terrible of young India, brought a kind of street chutzpah to Indian design that had not been seen before, channelling everything from Goa rave culture (his top selling t-shirt read ‘Full power, 24 hour. No sleep. No shower’) to the rambunctious style of Maharashtrian fisherwomen skimming the coastlines of Mumbai. His work took him to Delhi, Bombay, London and, finally, the coveted Paris Fashion Week calendar. “My rebellious personality at the time was pure creative fuel. And I went all out to prove it,” says Arora.

At the same time, Anamika Khanna, a seemingly docile female designer from a conservative Marwari family in Kolkata, brazenly upended the 5000-year-old tradition of the sari by shortening the length and width and pairing it with slick pants. It set the tone for her design oeuvre which, over time, deconstructed every revered traditional garment in the luxe Indian closet. “This experimentation with traditional clothing was unthinkable, but I was driven to find a modern language,” says Khanna. Just recently she shredded the lehenga, the hallowed South Asian bridal dress, doused in pearls, gold and silver, into a fired-up Mad Max-esque piece of couture. I remember clearly when this experimentation started. It was at the onset of a string of fashion weeks in India, at a time when I was weaving my own dream of becoming a fashion journalist. So our goals aligned: I wanted to write about fashion like a pop psychologist, and the designers simply wanted a writer who could pronounce Yves Saint Laurent correctly.

This was the beginning of the gig generation. Creativity and hustling went hand in hand. Dive bars like Bonobo and Aurus mushroomed across Mumbai, and the dodgier they were, the more we thronged them. One such dive was in a fisherman’s village in south Bombay called Cool Chef Cafe, where Japanese and English DJs raged the dancefloor till the wee hours of the morning, as well as my favourite: Bhavishyawani, a mad collective of French and Indian DJs.

Almost every night, our motley crew of DJs, musicians, models, artists and designers danced, flirted and went from party to afterparty to after-afterparty. Many nights ended at Champagne House. Moët & Chandon sent us complimentary cartons of bubbly when they heard about our vibe. The symphony of different cultures was most evident in my kitchen – fashion stylist Gary Wallang’s Nagaland pork curry, Mathieu Gugumus’s French soup, DJ Tejas’s Mumbai fish fry, and from my own Nepali repertoire, momos and gundruk curry, amongst many other lip-smacking delights.

“We wanted to celebrate where we came from, and honour craftsmanship across India”

At that time, design-meets-art shops like Bombay Electric, Ensemble and Bungalow 8 attracted South Mumbai’s hipsters, who were channelling the Bright Young Things of yore. Heritage lifestyle destination Good Earth, housed in a gargantuan 1920s textile mill, showcased a world of patina-artisanal brilliance from across India: Ayurvedic copper dinnerware, Mul-Mul and Khadi kurtas, Rajasthani hand-block linen, and Benarasi brocades – all ensconced in damask wallpaper and Mughal art, with new-age Indian classical music wafting in the air. By giving a modern twist to ancient crafts, Good Earth single handedly made heroes out of Indian artisans. “We wanted to celebrate where we came from and honour craftsmanship across India,” says Good Earth’s Simran Lal. Suddenly craft was cool. Good Earth soirees orchestrated by the rambunctious Beenu Bawa made sure the dress code was always ‘India-cool’, preferably handloom clothes worn with a sexy twist. And we did – saris worn with ‘bikini blouses’, bindis, bangles and jasmine braided into our hair.

At the forefront of bringing rural craft to urban India was a young Sabyasachi Mukherjee with his debut 2002 fashion show, ‘Kashgaar Bazaar’, inspired by prostitutes, gypsies and renegades who traversed the fabled Spice Routes performing extraordinary acts. Like his muses, we also yearned for that world of wanton abandon, and were eager to reclaim our playfulness, which had been suppressed by rigorous years in India’s Victorian boarding schools. He made being lasciviously erudite (today’s geek-chic) a force of nature. When his collection ‘Frog Princess’ was snapped up by Browns department store in London, it felt like every debutant could find a suitable partner. Today, Sabyasachi’s gargantuan flagship atelier in New York’s Christopher Street is testimony to the creative gumption of the early 2000s.

A regular sister in Champagne House was Little Shilpa, aka Shilpa Chavan, predominantly a milliner and accessory designer whose creativity sat at the crossroads of street and high art. She won accolades for her outrageous DIY creations made from discarded bangles, screws, safety pins, brooms, tassels, and bin bags. More recently, her 2023 film, HUM (we/us), bagged a series of awards at the Cannes World Film Festival, including Best Styling and Best Costume Design.

And finally there was the Crying Couch in Champagne House. Brick red in colour, but slightly faded from the salty air and sun of the Arabian Sea, it was cosy enough for three people to huddle together and cry in peace. In truth, I may have cried there for an entire year, clinging to my beautiful friends as I bemoaned my sad sitcom-worthy life: a philandering husband, a slew of sleazy coquettes, juicy tabloid fodder and the weight of an imminent but messy divorce. But on that couch, as I wailed to the view of a peaceful and buoyant sea, it became a safe, sacred spot not just for me, but for my melancholic gay friends struggling to come out to their parents, other jilted lovers and frustrated job hunters. The Crying Couch held our pains for many seasons as dreams in Mumbai sometimes tumbled and crashed. Like my red cushions, the sunshine bleached away our sadness.

"It was a time of possibility. Anything could happen, and it did”

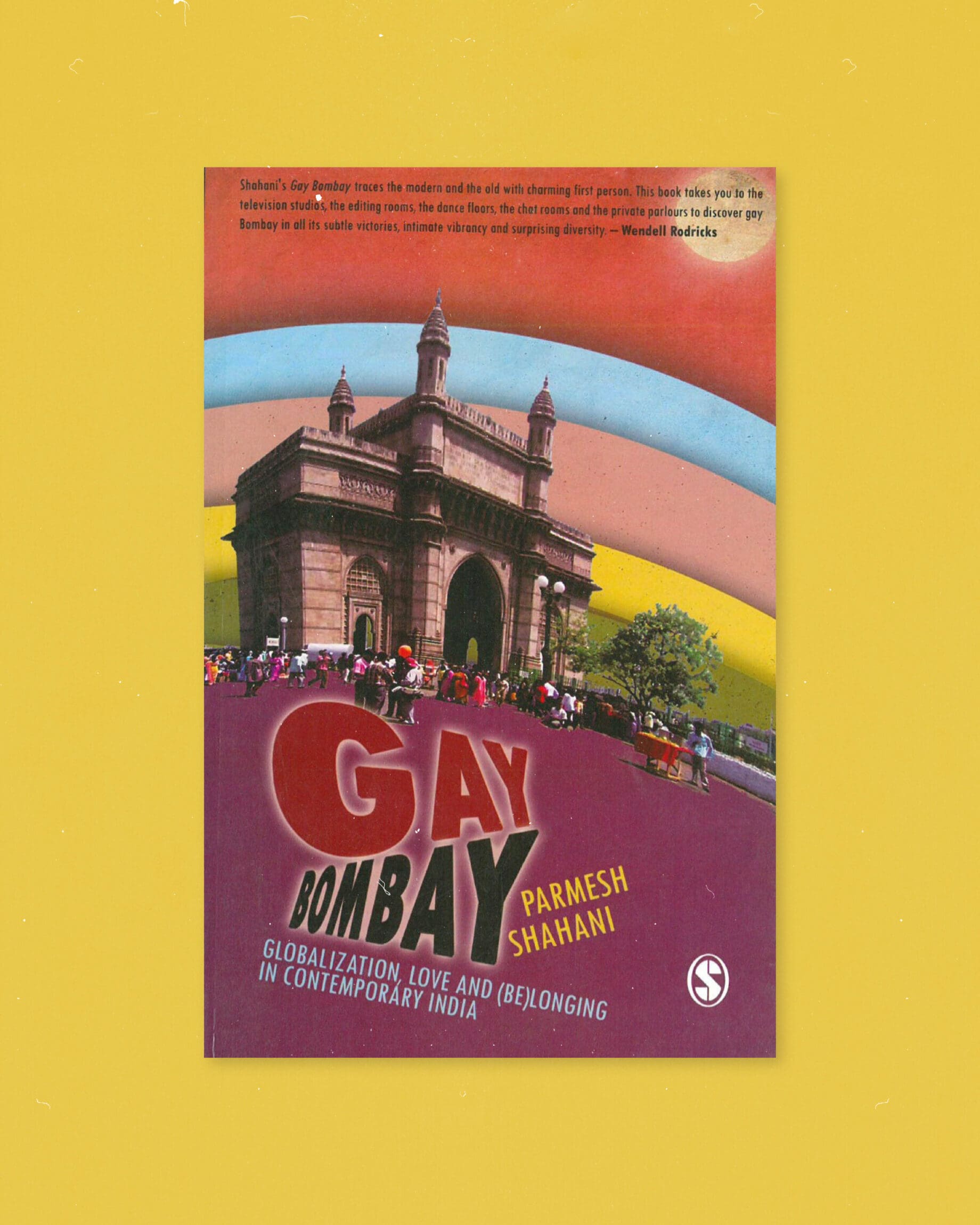

At a time when LGBTQ+ rights were shrouded in stigma and legal battle, my home was Mumbai’s gay haven of refuge. India decriminalised homosexuality in 2018, but this was the early 2000s, when it was still taboo. My friend and gay advocate, Parmesh Shahani, was researching his first book, Gay Bombay: Globalization, Love and (Be)longing in Contemporary India, in which he critically examined the formulation of contemporary Indian gayness in the light of its emergent cultural, media, and political alliances. More recently, Shahani has written Queeristan, which explores LGBTQ inclusion in the Indian workplace.

“Bombay in the early 2000s was in transition. There was a very physical queer landscape of public cruising, sex and nightlife,” says Sahani. “There were the walls of the Gateway of India, the washrooms at train stations, 2×2 compartments on local trains, parks like Bandstand, or seedy nightclubs like Voodoo.” He reminisces that all this was happening against the backdrop of a new post-liberalised Indian media with “beaming images of international gay prides, confessional interviews on Oprah and even early nods towards queerness through Bollywood films. Given that the laws were still against us, it was a time of possibility – anything could happen, and it did!”

Whilst the bells of change had started chiming, it was sheer naivety of our times that propelled us to be unpretentiously wild. There was no social media, no cancel culture; we were unperturbed, freely concocting crazy ideas, experimenting recklessly and being joyously smeared in our own fallibility. But most importantly, in a city in the throes of change and uncertainty, Champagne House was like an ever-lasting warm embrace. I still remember when Imran Amed and Nikhil Mansata fell in love there, at that time ever so cautious to keep it under wraps. Today, Amed, the brilliant founder of The Business of Fashion, and Mansata, a globe-trotting creative director, are now happily married. Champagne House, Number 69 was a microcosm of Mumbai, a city with a cavalcade of life, revealing a different story every ten yards; but for my friends, my daughter and me, that home, now torn down for a luxury high-rise, was a space where love was always a constant.