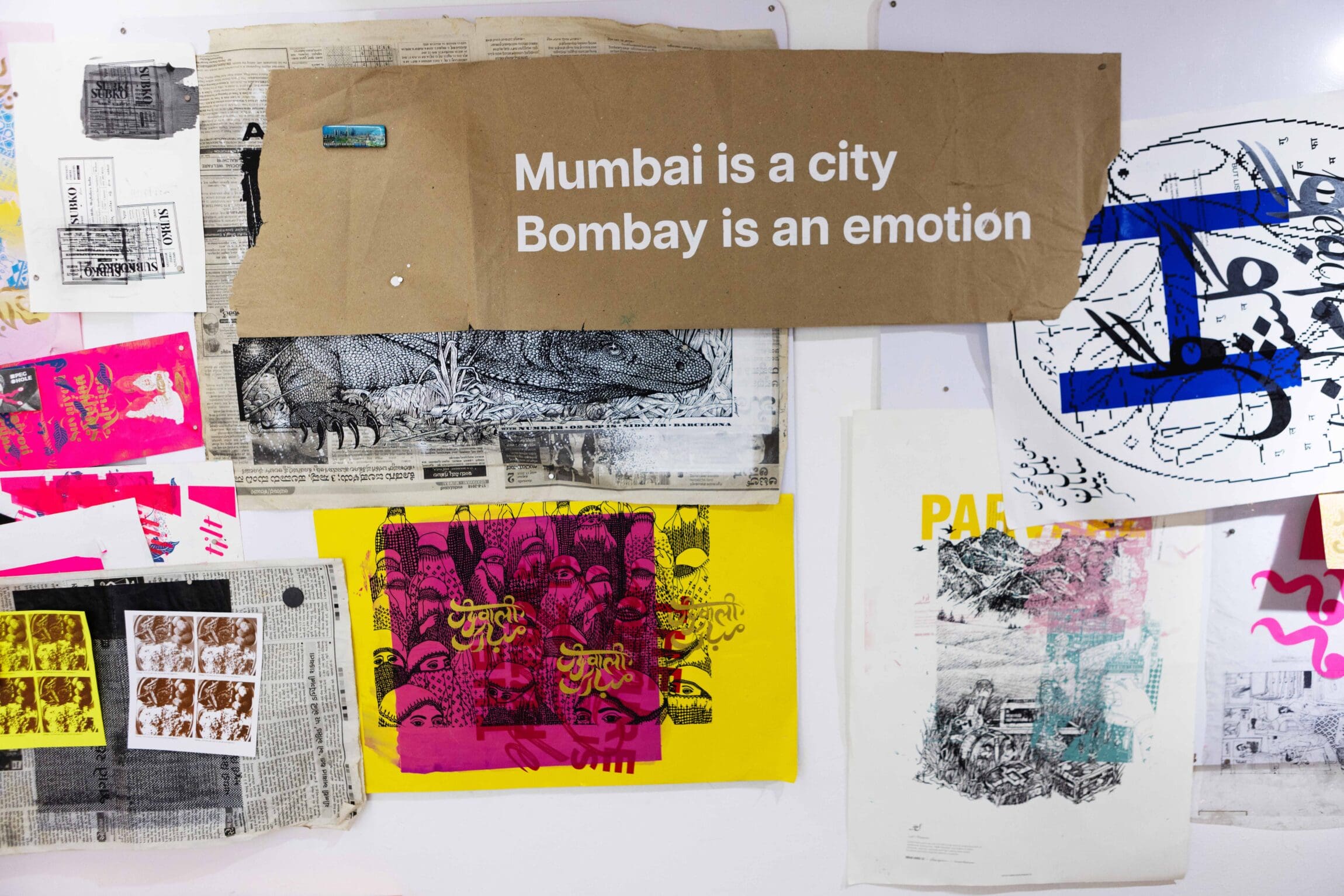

Mumbai artist Sameer Kulavoor on how the evolving megalopolis informs his work

Ahead of showing at Art Basel 2024 in Hong Kong, Indian artist Sameer Kulavoor discusses his creative practice, how his hometown of Mumbai has evolved and why travel is essential to forming new ideas

Mumbai-based artist Sameer Kulavoor creates geometric paintings, drawings, videos, murals and installations that explore architectural forms, and investigate how the built environment can tell us something about its residents, particularly in how they adapt existing structures. He is the founder of design studio Bombay Duck Designs, which is currently spearheaded by his sister, Zeenat Kulavoor. The studio works on diverse projects spanning publication design, exhibitions and brand identities with clients ranging from cultural institutions, artists, musicians and MNCs. He was featured in Netflix India’s 2016 docuseries Creative Indians and has collaborated with Paul Smith on t-shirt designs that paid homage to Mumbai’s cycling culture.

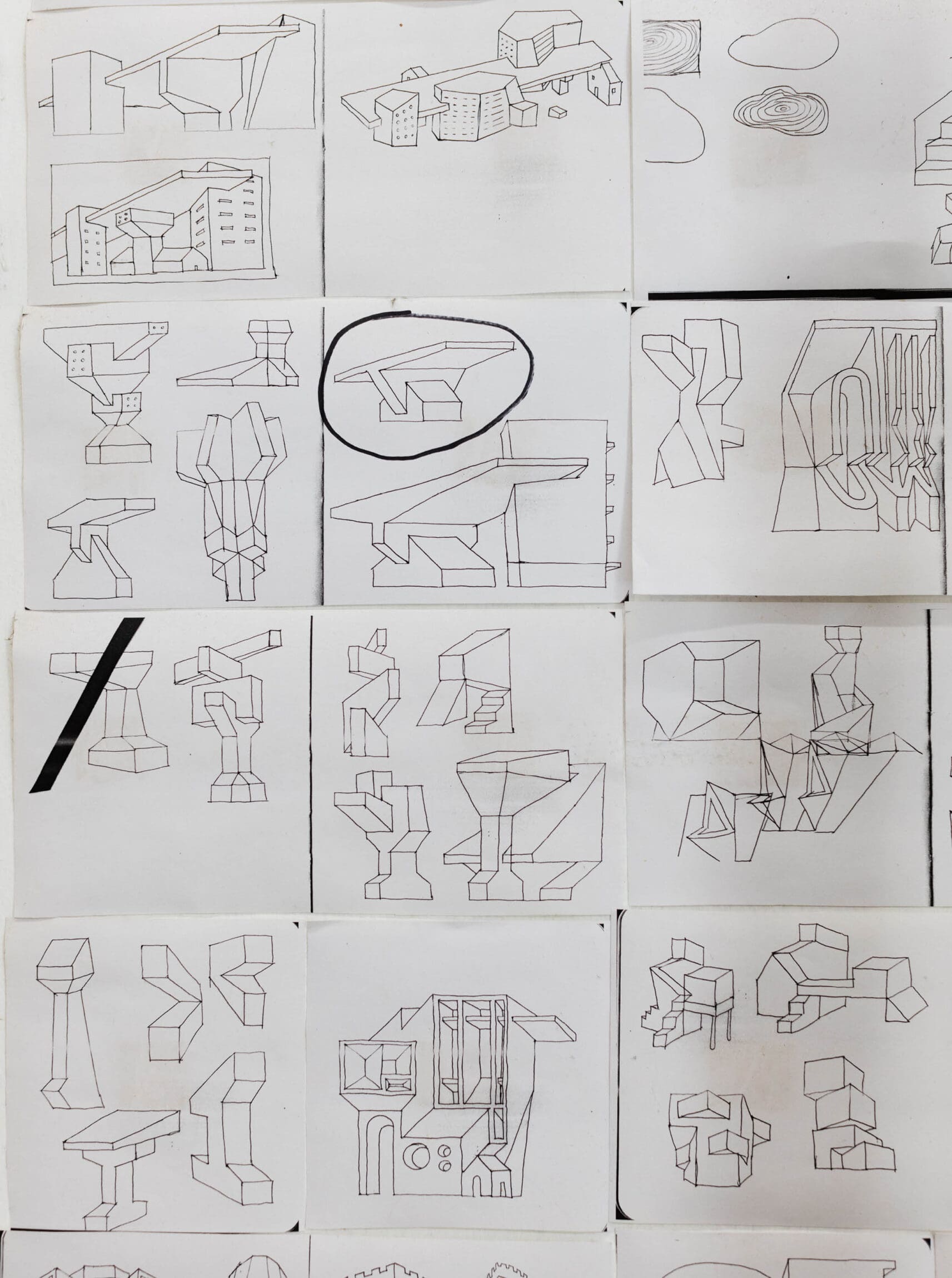

In 2023, Kulavoor held a solo show at TARQ Gallery titled Edifice Complex, where the artist’s sequential drawings and video pieces were shown for the first time. The video pieces reveal a sequence of constantly morphing architectural forms, geometries and perspectives shifting into new structures. Next to the video works, the drawings that make up the frames were presented in sequence as a frozen still life. He also worked on a series of installations for Mumbai Urban Arts Festival titled Metromorphosis, whereby miniature cities were built in hyper-realistic detail atop colourful fishing crates, as a nod to Mumbai’s original inhabitants – the indigenous Koli fishing community.

Kulavoor speaks to ROADBOOK from his Mumbai studio to discuss the pace of constant change in his home city, how that has fed into his art practice, and his ritual of regular travel to keep his work, and his impression of the city, fresh.

Tell us about your studio.

It’s currently in an industrial estate in Lower Parel, a central part of Bombay that was known for its cotton mills and textile manufacturing. One can still see traces of the past, remnants of the mills and the occasional chimneys in the area. The neighbourhood has completely changed in recent years with lots of malls and massive high rises being built. Parel now has the largest number of skyscrapers in Bombay.

That’s interesting to see that change happen. How else do you think Mumbai has changed while you have lived there?

I’ve lived in Bombay most of my life. I grew up here in the 80s. At that point we lived in the northern suburbs. I vividly remember we had to walk through okra fields from our apartment to reach school. That was the landscape back then. Now, when you go back to that same area, it has completely transformed – there is no sign of the past. Housing societies have replaced agricultural land, and there’s a major metro line and link road passing through.

There is an unprecedented number of new coastal roads, flyovers, bridges, subway and metro lines being built all at once in Bombay at the moment. It’s super inconvenient. My commute from home to studio shouldn’t take more than 20 minutes in a cab, but it currently takes an hour and a half.

Kulavoor’s architectural subject matter

A lot of your work is concerned with architecture. Do you often pay attention to these changes in the built environment around you?

Yes, I’m interested in how architecture can be thought of as a manifestation of the people that live there. You can look at the built environment and learn about its community and their concerns and the politics around it. Most of my work is about impermanence, transition and change, and I think that comes from my early experience of seeing how my neighbourhood underwent a drastic transformation in a very short amount of time.

Some of my work is about documenting things that might disappear, but also about how people adjust built spaces. What are the developmental codes of a city, what are you allowed to do, what are the laws, and what do people do to get around them? At first my work might seem architectural and all about form, but the deeper question is about the human condition.

So your work can be inspired by buildings that exist – that you want to record. Are there also fictional and imagined ones?

In the process of painting and drawing, it often does become an imagined building. I’m not too concerned with the specifics of a particular building. In that sense it isn’t purely representational or documentary in nature. For example, I’m interested in the elements that reveal a building’s age, the style or identity of the architecture and the sequence of development. You can tell by the materials: the facades of new buildings are typically covered in glass, but buildings from the 80s were concrete, and before that, stone. The materiality of a city leaves a time stamp.

For example, in the Kala Ghoda neighbourhood in Bombay, there are a lot of heritage buildings in the 19th century Indo-Saracenic style, which are now occupied by modern cafes, boutique fashion and lifestyle stores and heritage shops. The lanes are quite narrow, and most of the functional parts of the building are hidden at the back, such as the AC ducts, pipes and plumbing. I’m very interested in what’s going on behind the facade. People work hard to conserve these heritage structures, but my interest lies in what happens in the gaps. There is a tension between the past and present, and each inhabitant wants to have their own stamp on these structures. It is always changing, and that friction becomes very interesting.

"My work might initially seem architectural, but the deeper question is about the human condition"

Edifice Complex and Metromorphosis

You held a solo show with TARQ Gallery this year titled Edifice Complex. How did it go?

TARQ Gallery was moving to a new space after nine years in its previous location, and opened with my third solo show, Edifice Complex. There was a big shift between the works in this show and the previous one, so before it opened, I was a bit jittery. My previous shows featured a lot of figurative work, predominantly acrylic on canvas, whereas in Edifice Complex, I painted architectural subjects on paper, transparent glass and acrylic sheets.

I included 19 video works, which were produced from sequential drawings. The videos played in small wooden video boxes, and the original sequential drawings were also shown as still frames.

You also worked on Metromorphosis this year, a series of collaborative installations with Sandeep Meher. How did that collaboration come about?

That was part of Mumbai Urban Arts Festival, which was organised by St+Art India, an organisation that identifies public spaces and curates contemporary urban art. The festival was held in a 150-year-old fishing dock in the south of Mumbai that’s active to this day.

I wanted to make something that would honour the Koli fishing community. They are the indigenous inhabitants of Bombay, and for the last 300 to 400 years, their land has slowly been usurped by the city. I was thinking about their livelihood and their fishing process, and thought that the colourful plastic fishing crates they use could act as a striking symbol for their work. I wanted to tell the story of this change over the last few hundred years, so I used these fishing crates as the base for the installations, and built a miniature metropolis atop these crates.

The miniatures were hyperrealistic and very detailed. I invited Sandeep Meher to work with me. We are old friends and we studied together at art school. He works in production design in Bollywood, and he belongs to the Koli community from Dahanu, in the northern suburbs of Bombay. I did some detailed concept drawings, and Sandeep helped realise the concept with his team by building the miniatures.

The idea was to bring together many different architectural styles to reflect the multiplicity, complexity, scarcity and density of Bombay, as well as the retrofitting and adjustments that people make to their environment over time. The installations were up for about 90 days, open to the public, for free.

What projects are you currently working on?

I’m steadily working on my sequential drawings, and have been working on pieces that are loosely based on my recent experience visiting the UK. When I was in Edinburgh, the thing that stood out was the topography – there are so many levels. Edinburgh must have been the Tokyo of its time. You can be on a road and enter an establishment at ground level, and realise the building extends five storeys down. It was interesting to witness that.

I will also be showing at Art Basel in Hong Kong in March next year. I will have a solo booth with TARQ Gallery, showing my drawings, paintings and video works.

The influence of travel on Kulavoor’s practice

How does travel inform your work?

After travelling and experiencing a new city, when I come back home, I see my city through fresh eyes. It’s like when you’re testing perfumes, you have to smell the coffee beans. In some sense that is what happens to me. I come back home and I’m all open and look at the city in a much better way. It helps form new ideas.

As a rule, I make sure to spend about 40 to 50 days a year out of the city. I decided to try this early in my career, and it worked so well for me. These longish singular journeys outside my normal surroundings always have a tremendous impact. It is good for mental health as well and for a strong bout of inspiration and new ideas, and to avoid getting rusty, stagnant and desensitised, which tends to happen when you are stuck in one place for too long.

Last year I visited Oslo, Berlin, Basel, Milan and Venice, during the biennale. Around the time of the second lockdown, I was in the north of India, in the Himalayas. I’ve taken a long trip to southeast Asia, and to Scandinavia. It’s interesting to see how certain regions are built up in a very different way over time.

Is there a destination you would like to visit that you haven’t been to yet?

I would love to visit Mexico. I haven’t been to Central or South America yet, and I would also love to revisit Japan. In 2015, I was in Tokyo and Kyoto and would love to go back and spend more time there.

Bombay is catching up right now to meet the demands of the population

Do you have a memory of your trip to Tokyo that stood out?

I spent a lot of time around Sumida River – there was a lovely view of the city along the bank of the river. I remember going to a number of design and stationery shops around Harajuku, Ginza and Roppongi, as well as Mori Art Museum and lots of sushi bars. I also visited Tsukiji fishing market, which was demolished to make way for the Olympics a few years later.

What does Bombay mean to you?

It’s an intense love-hate relationship. There are times when I hate it here because it is so hard to function, real estate is expensive, the cost of living feels high, and the traffic can sap your energy. But when I think of home, it is not my immediate house – it is the city itself. The city is constantly under construction, there is constant change, and you always wonder if it is going to be good or bad for the city. Part of my mind is always engaged in those kinds of thoughts.

A few months ago, I was thinking, if one were to temporarily relocate out of Bombay, and come back three or four years later, you would return to a completely new city. There are some planned developments that are absolutely essential, and are already 30 years late. The metro line should have been updated in the 90s. Bombay is catching up right now to meet the demands of the population, and to make sure the planes, roads and bridges are safer and allow for as much accessibility as possible. Unfortunately it is just all being done at the same time, and is causing a lot of trouble. But it will be a very different place to live in three years. Good or bad? I am not sure.

What do you hope people feel when they experience your work?

I don’t work with an end goal in mind. As long as the work moves someone and makes them stop, look and think in some way, I think that’s great. Everything beyond that is a bonus.

My practice is not a passive one – it’s very active. A lot of my work is in sequences or in multiples. I work ten days a month, but when I work, it is a very intense period of production. I am fast at my work, and I am really into it, and then I have some days where I let myself breathe. When I’m in the flow, I don’t want to stop, but it takes time to arrive at that point when you know you are making compelling work. Some of the work does end up in the bin.

I always take a step back and look at my work with fresh eyes. When you are too close to the work, you can lose judgement sometimes. And ultimately, you are the most important critic of your work that leaves the studio.