In Motion: Hiking through the vestiges of wildfires in LA’s Santa Monica mountains

Hiking in Los Angeles has enjoyed a boom since the pandemic. Our local writer explores the trails, and finds the scars of forest fires on the ever-changing landscape

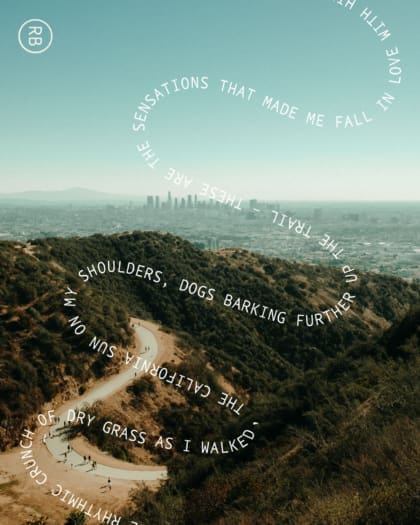

The rhythmic crunch of dry grass as I walked, the California sun on my shoulders, dogs barking further up the trail – these are the sensations that made me fall in love with hiking during the pandemic. I started with sojourns around the block just to get away from my studio apartment in downtown Los Angeles during lockdown, but soon traded in those little concrete-encased strolls for steeper five-mile hikes with ocean views in the city’s famed hills.

There’s quite a lot of ground to cover: the city of Los Angeles, vast and sprawling, sits on a coastal plain between mountains and the Pacific Ocean, while nearly half of LA county is made up of mountain chains – San Bernardino and San Gabriel run to the north and north east, and the Santa Monica Mountains and San Jose, Repetto, and Puente Hills sit almost directly in front of them, stretching all the way from east to west.

The result is hundreds of trails to choose from, including the crowded paths that lead directly from city streets up to the Hollywood sign. In fact, hiking is one of the four main Angeleno hobbies, alongside the movies, the beach, and brunch at one of LA’s great restaurants.

Hiking has enjoyed a recent boost in popularity since the arrival of Covid, and you’ll see photos of sun-drenched trails peppering social media feeds, the hazy Los Angeles cityscape in the background. But if you strike out on the trail yourself, you’ll likely see sights that don’t quite make the Instagram edit: the scars left in the wake of recent forest fires.

It’s a recurring theme on my many winding walks around the Santa Monica Mountains – beautiful flowers bloom next to the charred remains of trees, and mudslides wash out parts of popular trails.

If you strike out on the trail, you'll likely see sights that don't make the Instagram edit: the scars left by recent forest fires

Out in Malibu – a hiking area slightly further away from the city that rewards your longer journey with a connection to nature less tainted by smog and urban noise – you’ll find the Solstice Canyon Loop Trail, which has become one of my favourites. This easy, flat three-mile loop leads hikers almost directly from the beach into the hills and back. It’s well known for being both picturesque and accessible for hikers of any level (and it has free parking).

About halfway through the trail, you’ll come across ornate brickwork pillars overgrown with greenery – empty, ruined fireplaces echoing ghostly grandeur in the bright California sunlight. These are the haunting ruins of the Tropical Terrace estate, a mansion occupied by supermarket magnates in the 1950s. In 1982, the stately home was almost completely destroyed by the Dayton Canyon Fire, a brush fire that was blown out of control by autumn winds. It ultimately claimed 125 homes and burned an estimated 50,000 acres of land. Now, the Tropical Terrace ruins remain on public land, a monument both to architect Paul R. Williams and to the devastating impact of forest fires.

Forty years later, the Solstice Canyon Loop Trail bears the vestiges of the furious blaze, as well as tentative seeds of regeneration. The grasses and flowers have grown back; yucca plants thrust sword-like leaves and white flowers ten feet into the air. Some trees survived, and their new growth makes the trail a pleasantly shady walk. One particular tree sustained damage that left sections of it hollowed out. But in many places, dead trees stick up like broken bones protruding from the ground as charred reminders of the damage.

Today, Angelenos tend to joke that Los Angeles is visited by four main seasons: spring, summer, fire, and awards – the Oscars, Emmys and Golden Globes filling in the gap where other regions of North America experience winter. Fire season, however, has become all too real in the last half century, brought on by a combination of devastating droughts and modern land maintenance practices that have left the region vulnerable to wildfires that take years to heal.

While these fires pose a threat to the Angeleno habit of going for a hike to earn your brunch, they hold much greater cultural and spiritual significance for the Chumash and Tongva Native Peoples. Less than 300 years ago, this land was stolen from the tribes – and is still considered sacred today. Under the stewardship of these tribes, such devastating wildfires were unheard of.

Alan Salazar, an educator and Elder of the Chumash, spoke frankly with me about the tribe’s history with fire in the region. “No historical notes ever mentioned anything about fires getting out of control,” he says. The Chumash and other Indigenous groups in Southern California practiced what today is called controlled burns: when people deliberately start controlled fires, “carefully thinning out the brush in smaller areas” to prevent a build up of dead plants from becoming fuel for devastation.

This ancient practice removed dried brush and allowed plants with edible roots more room to grow, which was the goal for the Chumash. But when state and federal forestry services took over the land, controlled burns were forgotten. Dried brush built up year after year. Invasive plants moved in, choking out the deeper root systems of native plants. Together, this has made the region susceptible to both infernos and mudslides.

Modern LA is paying the price: the Woolsey fire in November 2018 tore through parts of Los Angeles and Ventura, killing three people, displacing 300,000 people, and destroying 96,949 acres of land. It roared at the borders of Los Angeles too; drivers on the 405 highway, which winds through the hills, watched as embers crawled through Getty View Park and toward the iconic Getty Museum. For months after, the land was a charred, black mess. Winter rains came through next, causing mudslides and setting recovery back further.

The immediate impact of the fire was devastating – the air was nearly unbreathable because of the smoke – but it took time to see how far-reaching the consequences really were. Entire sections of Malibu and Ventura became inaccessible and unliveable. Not only were structures destroyed, but animals were pushed out and hiking trails were severely impacted, remaining closed long after the blaze cooled.

Salazar suggests more controlled burns could spare the region from future infernos, protecting it for both the people and animals that live here. “We have access to knowledge and information that my tribal ancestors didn’t have,” he says. “Because of radar, they can predict, usually within an hour, when a storm will start. So if they can predict when it’s going to start raining, why isn’t the Forest Service out there clearing fire breaks and starting a fire in the evening, with fire trucks and mother nature as our backup system?” Bringing back controlled burns would remove much of the fuel that allows fires to get out of control.

Los Angeles is home to a profound dichotomy between nature and city. Because of that, hiking in LA can feel magical. The mountains offer a break from the daily struggle of smog and traffic, and provide an accessible connection to nature and to a shared past. Without better protections in place, every autumn we risk losing those hillside trails, and some of LA’s irresistible magic.

For more ways to get under the skin of Los Angeles, try our insider guides, covering everything from the best rooftop bars to the coolest coffee shops and the most beautiful hotels in the city.