A journey to Thailand with Saiphin Moore, co-founder of Rosa’s Thai

Saiphin Moore traces her journey from a street food stall in rural Thailand to building Rosa’s Thai, one of the UK’s most successful restaurant groups. She discusses how Thailand’s inimitable flavours, flaming woks and rolling rice fields have shaped who she is today

Every day, from the age of 12, Saiphin Moore walked three miles uphill to a small patch of land in Khaem Son, in the Khao Kao district, a mountainous region of northern Thailand close to the Laos border. She grew cabbage, carrots, leeks, kai lan (Chinese kale) and radishes. Saiphin sold much of her produce to noodle shops nearby (an early indicator of her entrepreneurship), and at just 14, she opened a stand in Phetchabun, the capital of the province. There, against the backdrop of an enormous Buddhist temple, the structure gleaming white in the sun, head gold and stretching up towards the clouds, Saiphin would cook the likes of pad kee mao, or drunken noodles, heavy with birds-eye chilli and holy basil.

Today, her farm sits dormant, the land disputed and unkept. Shrivelling wisps of coriander still grow in places, but otherwise it is overgrown and dry in the stifling heat. “I would sit on this hill with my dog,” says Saiphin, visibly emotional. “It all started here. I worked hard, I left school early but I had a plan. I saw a real aeroplane for the first time up here – I didn’t really encounter electricity until I was a teenager – and something in me said, ‘I must go, I must get on one of these’.”

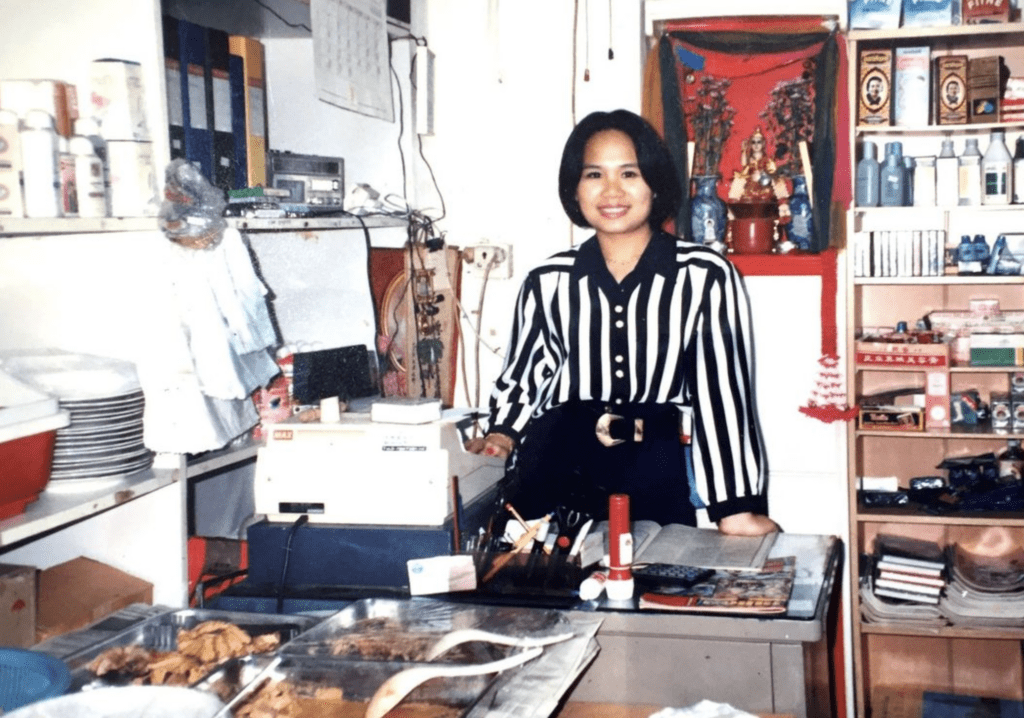

Saiphin had been taught to cook by her mother and aunts. After years of running her own noodle stand, she had gained experience that extended well beyond the confines of the family home and had saved enough money to enable her to travel. At 18, the young chef moved to Hong Kong, took a job as a nanny, and eventually managed to open a grocery restaurant in the city. Then came the first of two now-finished marriages and a move to Jersey in the Channel Islands, where she would take trips to London to buy Thai ingredients. After the first relationship broke down, she returned to Hong Kong and opened a new venture: a 30-cover, always sold out cafe called Tuk Tuk Thai, which she later sold to fund a permanent shift to London.

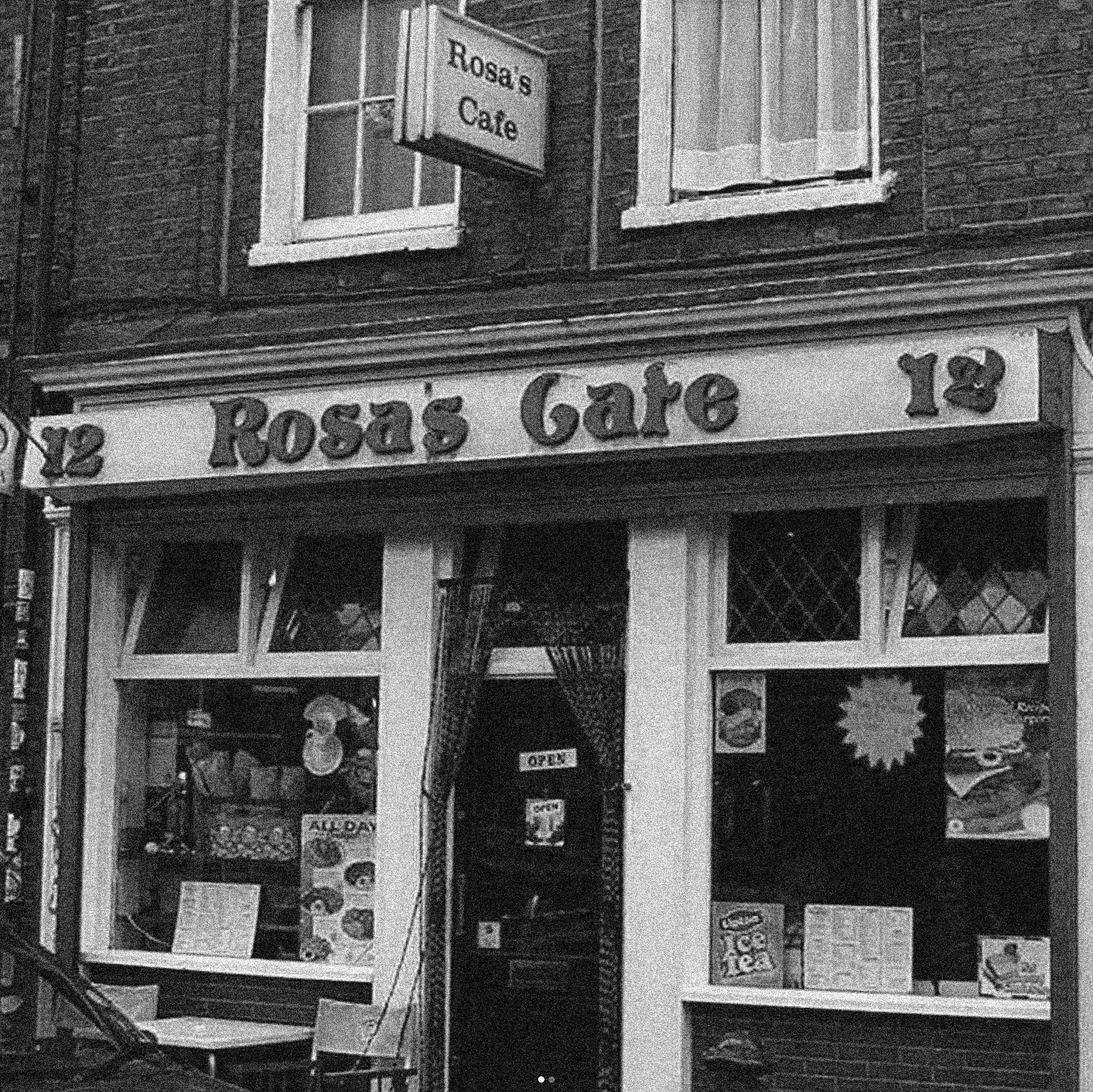

Saiphin settled in Wapping in east London, next to the River Thames, and ran a catering business from her home and a food stand on Brick Lane. This became the first site in what is now a national brand. With no money to change the existing signage from the previous business, called Rosa’s Cafe, the name of what is now the UK’s most famous Thai restaurant chain enshrined itself: Rosa’s Thai. “I still get asked who Rosa is,” Saiphin says, nonchalantly. “Rosa is nobody; she’s me; she’s somebody – it doesn’t matter. It works.”

In the early days of 2008, Rosa’s Thai was an independent restaurant. Thai cooking was mostly still the preserve of pubs – light curries, spring rolls and maybe a fishcake or two – and neighbourhood fixtures for those au fait with the fiery flavours. There was space for an accessible, affordable chain serving interesting dishes in an approachable way. Expansion was organic and gradual to begin with, before private investment in 2018 helped to accelerate growth. Now sites are popping up apace.

Today, diners from Liverpool to Leamington Spa, Glasgow to Exeter order bowls of Saiphin’s moo ping (barbecued pork skewers), plates of tod man khao pod (sweetcorn fritters) and stacks of gai hor bai toey (pandan chicken parcels). The heat is tempered to suit British palates, ingredients too: there are no crab legs in the papaya salad, as there are back home; offal is a rare and unkempt novelty rather than par for the course; recipes are crowd-pleasingly pan Thai. But there are nods to the food of Saiphin’s home in lower northern Thailand, an area that passes largely unnoticed by tourists heading to Chiang Mai to the north west, Bangkok to the south, or the islands of Phuket and Koh Samui. “We have to appeal to all our customers,” says Saiphin. “People in Britain love Thai food, but most do not want proper spice or more unusual dishes. Sometimes we experiment but if people want pad thai, that’s fair enough.”

We begin our trip with a night in Bangkok, where Saiphin seems as much an excitable visitor as the rest of us. We visit Jack’s Bar, a cafe perched over the Chao Phraya River. It’s a place for Chang beers served in iced glasses, pad sataw kung ( pungent sator beans with shrimps), squid in yellow curry powder, and deep-fried white fish topped with soy, chilli, ginger and galangal.

Those who are familiar with Bangkok will be aware of the enchanting nature of Jack’s Bar. There is something deeply alluring in the mesh of painted metal, brushed wood and swinging bulbs; of strips of neon lights; wafts of heavy, fragrant smoke and the clatter of beer bottles; the background thrum of an endless parade of mopeds. When Bangkok comes together in that way, it is the most romantic city on earth. It is a place to get lost in: each night a sensorial episode, one that brings about an intense feeling of belonging, all the while stepping out of the comfort of oneself.

“We should enjoy Bangkok, we’re only here for a night,” says Saiphin. Who are we to argue? We visit more bars, time slips away, and the morning flight south to Trang, a coastal jungle-clad region that etches into the turquoise ripples of the Andaman Sea, is less than enthusing.

“Into vast blue buckets go a ferocious amount of eye-watering spice”

We head to Trang to visit the factory where Rosa’s curry pastes are made. Great swathes of the land there are used for the production of delicacies such as pak boong (morning glory), pak kwang tung (mustard greens), pak choi (bok choi), raak bua (lotus roots), pak chee (coriander), and plenty more besides. We trundle on dirt roads up hillsides and through thick jungle to see where extended members of Saiphin’s family cultivate vegetables, leaves, spices and herbs.

At the newly built factory baking in the southern Thai heat, curry pastes are made in bulk before being shipped to Britain to be used in dishes at Rosa’s Thai restaurants. “You must get the ingredients in Thailand – you can’t get the right quality or flavours otherwise,” she affirms. “It’s easier and cheaper for us to grow and make this here. I want to make sure we still do things properly. These different curry pastes are the basis for our cooking.”

Into vast blue buckets go a ferocious amount of green chillies, garlic, shallots, coriander, holy basil, ginger, and more. It all billows into the hot air, blasting the room with eye-watering spice, before being cooked with palm sugar in enormous flame-licked woks at the other end of the kitchen. “They’re making green curry paste today,” she explains. “It’s the perfect recipe for us.”

We then head far north to Saiphin’s home in the farming bolthole of Khao Koh. It is a cooler region by Thai standards, surrounded by jungles rich with tamarind, coffee, strawberries and cabbages. “We have lots of things that don’t grow in other parts of Thailand. It’s an area without much money but rich in food.”

I wonder whether Saiphin might be the local area’s wealthiest person. Rosa’s Thai sold in 2018 for £20 million ((Saiphin still retains a level of influence and control). Expansion plans are afoot thanks to investment from private equity firm TriSpan and Barclays, not that you’d know. On our final night, Saiphin isn’t luxuriating, but ever present in the courtyard outside her home, cooking under tarpaulin as any Thai matriarch might, fairy lights abuzz and the promise of karaoke after dinner.

The list of dishes she prepares is never-ending, an innumerable wheel of classics. Saiphin makes pad kra prow (stir-fried pork), pad pak boong fai dang (morning glory in oyster sauce), pla kapung neung manao (whole steamed river fish with garlic and lime), and tom yum (hot and sour soup, rich and deep with lemongrass). There are bowls of sticky rice and a whole pig cooked low and slow over a spit, skin crisp, meat tender and forgiving. It is to be dipped in red chilli sauce, one that brings with it a layered, intense heat, deeply moreish and absolutely lethal.

“I love cooking, and I love feeding people,” she says, as ice-cold beers are plucked from buckets, Sangsom rum is poured, and family members eye the microphone and its booming speakers on the front porch. Later, there will be dancing. “Are you hungry?” she asks busily, frantically, smiling. I have eaten half of Thailand. “Look, have this.” It is half a fish.

All this, I suppose, is totally natural: it cannot be replicated in dining rooms back home, in the muted towns and cities of Britain. To see woks aflame with Saiphin rolling out rapturous plates of rice noodles in a freshly painted restaurant in Guildford would not capture or garner the same effect as here. But that is, to some extent, the intention: Rosa’s Thai started here; a business founded by a young, ambitious chef, cooking noodles from a stand for locals in her home town. It cannot be imported, but the curry paste can.