The rise of domestic rural travel in China

When national borders closed during the pandemic, Chinese urbanites turned to their own countryside and were pleasantly surprised. Jacob Dreyer explores how China embraced its slow side and became a world leader in rural tourism

“Come for the harvest,” says revered Chinese architect and activist Ma Qingyun. We are standing in Jade Valley vineyard, the winery, hotel and spa he founded in 2000, in the village where he grew up, in Lantian County, Shaanxi. It’s an hour’s drive from Xi’an – China’s T’ang dynasty capital – but it feels removed from urban life, closer to the Chinese saying 天人合一 (humans and nature are as one).

Ma was the first from his village to be awarded a place at the elite Tsinghua University. This opportunity launched his career, during the course of which he became friends with other architects like Rem Koolhaas, with whom he collaborated on the CCTV Tower in Beijing and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, and went on to serve as dean at LA’s USC Architecture School. His firm, MADA s.p.a.m, built projects all over a growing China, but as a theorist he’s perhaps best known for championing rural values and design. Jade Valley was the home of Ma’s ancestors for generations (his family name identifies his clan as horse merchants).

Ma’s vision of urbanism is deeply intertwined with agriculture, and ideas of civilization from Chinese history. At his headquarters in Xi’an, he drew me a map of ancient Chang’an, with mountains and old roads, and explained how Chinese civilization evolved with reference to local geography that was both intoxicating and detailed. If that is his theory, his vineyard and the circular economy that it seeks to create are his practice.

China’s development has been so fast that in the span of a single lifetime, it has urbanised and globalised, before pausing to search for its roots. Ma has followed China’s journey into a new sort of society, one with a renewed appreciation for ecological sustainability and cultural identity, in rejection of the fast-paced and generic cities that have been built over the past 20 years. His vineyard and resort is a comprehensive effort to build a local economy that exports China’s traditional culture on its own terms. The vineyard produces 100,000 bottles a year for customers throughout China who hunger for products from their own soil.

The evolution of rural China

Over the past ten years, the concept of travelling in rural China has completely changed, transformed by the high speed railways and highway system that make even rural Tibetan Mountain villages easily accessible. In 2023, the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) declared China a leader in rural tourism, and praised its support of rural development.

China’s middle class has grown to around 300-400 million people, many of which have disposable incomes and an interest in visiting villages, where not so long ago, the majority of the population were trying to escape the village in search of better economic prospects.

How the pandemic led to a rural tourism boom

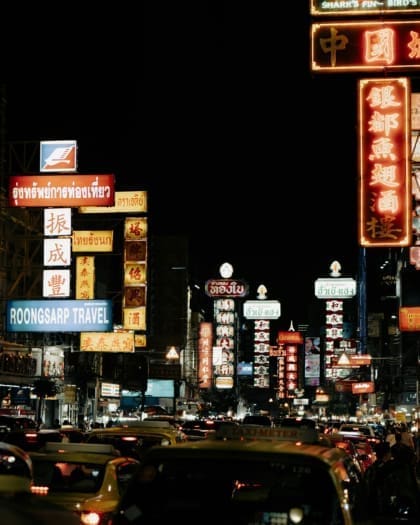

During the first years of the pandemic, my family and I travelled freely around China, even as national borders were closed. Forced by circumstance, we, like so many other urbanites in China, discovered China’s village life at family-run guesthouses and boutique hotels, often in stunning natural environments. With borders closed, we couldn’t go to Thailand or Paris or Hokkaido anymore; and we soon discovered that wasn’t necessarily such a problem. China’s countryside had always been there, like old furniture in the room we never opened; all of a sudden, we discovered that these were precious antiques, with a flavour all of their own.

"Rural China is the antidote to city life – swapping concrete for wood, car horns for chickens

The value in old China

In 1949, when the PRC was founded, 89 per cent of the population were rural, mostly engaged in subsistence farming, from the fishermen of Shandong to the tea fields of Zhejiang or the fertile farmland around Chengdu. Accordingly, each of China’s regions preserve their distinct cuisines, architectural styles, and old houses – often entire villages – that have been abandoned in the rush to urbanise. Today, an increasingly large number of resorts and businesses are noticing the value in rural China – its people, lifestyles, cuisines and landscapes – and have established themselves in the countryside to offer food and wellness experiences for city dwellers to discover.

Where to experience rural China at its best

Unlike ten years ago, you no longer need to live like a backpacker to access the rural beauty of China. “Caught between a desire to experience rustic charm and a lack of creature comforts, city dwellers can be at a loss for where to stay in culturally rich yet remote destinations in rural China,” says Sean Wilde of boutique travel agency The Hutong. “Are they willing to enjoy Guizhou’s Miao region if there is no mountainview bathtub suite?” In a country with a rapidly growing population, market forces have answered the question for him. Even in the most remote and poor regions of Southern Gansu, Qinghai’s Himalayan desert, or tropical jungles filled with ethnic groups with unique customs, there is now accommodation that suits well-heeled travellers.

Set in Jiangxi’s dense green forest, Wuyuan Skywells is a restored 300-year-old Huizhou mansion turned into a boutique hotel by Englishman, Ed Gawne, and his wife Selina, who grew up in nearby Nanchang; they’re raising their two kids are in the village. “I see it as the perfect antidote to Chinese city life – swapping out wood for concrete, chickens for car horns and getting lost in the hills when the whim takes me,” Gawne says. From Shanghai, the fast train takes three hours; you could leave the office at 6pm and plausibly be tucked up in your bed at Wuyuan Skywells at 10pm. Waking up, you’re in a land of sunbeams on rivers, fresh tofu and forgotten temples.

Dali, a city in China’s southwestern Yunnan province – nicknamed ‘Dalifornia’ by the urban escapees who crave its laidback lifestyle – guesthouses and organic restaurants abound, overlooking Erhai lake (named after its resemblance to an ear). Temperate climates and great cuisine have made life in Yunnan increasingly compelling for urbanites fed up with Beijing traffic and Shanghai prices. Here, as in Jiangxi or Hainan island’s Sanya or Zhejiang’s Huzhou or a mushrooming number of locations around China, you’ll find bohemian youth looking for a different way to be Chinese.

An hour’s drive from Dali is Sisan Shuanglang hotel. I learnt of it from the gallerist Matthew Liu; one of his friends, a design maven from the megacity of Chongqing, had built it as a retreat. A sophisticated vibe, with books from designer Xie Ke’s collection in the rooms, the hotel looks out onto the lake in the region that Chinese call the land of eternal spring – it is never winter here, nor summer, but always temperate and calm.

Here, as in Jiangxi or Hainan island’s Sanya or Zhejiang’s Huzhou or a mushrooming number of locations around China, you’ll find bohemian youth looking for a different way to be Chinese.

In the powerhouse province of Guangdong, where a population of 126 million fuels an economy the size of a European country, the concrete jungle is surprisingly easy to escape. About an hour’s drive from Guangzhou, the provincial capital, Hong Kong’s New World Group has a wellness resort, the New World Qingyuan Hotel, which features 217 rooms and is surrounded by hot springs. The vibe is slick and luxurious, set in a lush rainforest, down a remote country road. The resort offers delicious local food, like fresh tofu made from black beans, or braised green vegetables you’ve never heard of before that taste like eating pure springtime.

China is transitioning from venturing internationally to exploring its own country

Going home

Before the pandemic, China was the biggest source of outbound tourism around the world; whole economies from France to Thailand relied on Chinese tourists. The expected rebound post-pandemic has been more subdued than expected, based in part on China’s economic turbulence and fewer flights. But in truth, China’s society is transitioning from venturing internationally to exploring its own country. For example, I asked Ma Qingyun if the covid years had dented revenues at Jade Valley vineyard. In fact, he told me, the past five years had been the best ever: people from Xi’an who might once have gone to Europe were now driving to Lantian County instead.

On our way back to the airport, we stopped at a house Ma built for his father 25 years ago. Driving through the village, Ma couldn’t help but complain about the ugly houses that had been built in the past 20 years; it’s a sentiment one hears from many Chinese, as they remember the value of what has been lost. He pulled his car to a stop next to a group of men drinking in the late afternoon sun; one, his older brother, still lived in the village full time, where he keeps bees, rare trees, and makes vinegar and cheese.

Tsinghua University and globalisation brought Ma around the world; his brother had stayed at home, and smiled as he handed us walnuts dropped from the tree, crunchy and green. With the Chinese of a certain generation, one sometimes feels that they wonder if the whole thing has been worth it – the money, the Harvard, the Paris, all of that. We headed back to Shanghai with the sun slowly fading to night.