Hedonism, healing and credible science – where next for drug tourism?

Psychedelic retreats are booming, and evolving science and legislation are opening up new destinations. We explore the intersection of drugs and tourism and ask what’s next for those who fly to get high

Whatever your moral perspective, drug tourism is big business right now. A recent study by booking.com found that 14 per cent of travellers were interested in psychedelic retreats, while the number of such destinations listed around the world rose from 64 in 2020 to 362 in 2023. The domestic American cannabis tourism business is reportedly worth 17bn USD, and the US weed industry as a whole employs more than 440,000 people.

These numbers are underpinned by a broad global transition towards more liberal drug laws. While there are still countries with highly punitive punishments – Saudi Arabia, for instance, has executed more than 50 people for drugs-related offences in 2024 alone – we are now seeing a tide of research into the medical value of substances that were used many millennia before the advent of America’s increasingly derided ‘war on drugs’ – the attritional campaign started by President Nixon in 1971 that has, despite its best efforts, resulted in a global illicit narcotics trade worth around 500bn USD.

Unsurprisingly, a plethora of businesses are trying to hustle themselves a corner of this nascent and endlessly contentious industry. They have been helped by various celebrity endorsements, with everyone from Prince Harry and Gwyneth Paltrow to Mike Tyson espousing the life-altering benefits of a psychedelic journey. (The latter even sells branded ‘Mikeadelics’ magic mushroom grow kits and is the face of an Amsterdam coffeeshop called Tyson 2.0.)

Yet before unpacking drug tourism’s high and lows – and the research indicating what’s putting bums on airline seats – first, some history.

The origins of drug tourism

In her 1994 article ‘Drug Tourism in the Andes’, anthropologist Marlene Dobkin DeRios explored the trend of westerners travelling to the Amazon to “participate in drug rituals with the hallucinogenic vine ayahuasca, among so-called native shamans or witchdoctors”.

DeRios writes that, although travelling to use ayahuasca – a substance that induces deeply introspective psychedelic trips – was a “relatively recent postmodern phenomenon of consumerism”, drug tourism itself wasn’t a novel proposition to westerners.

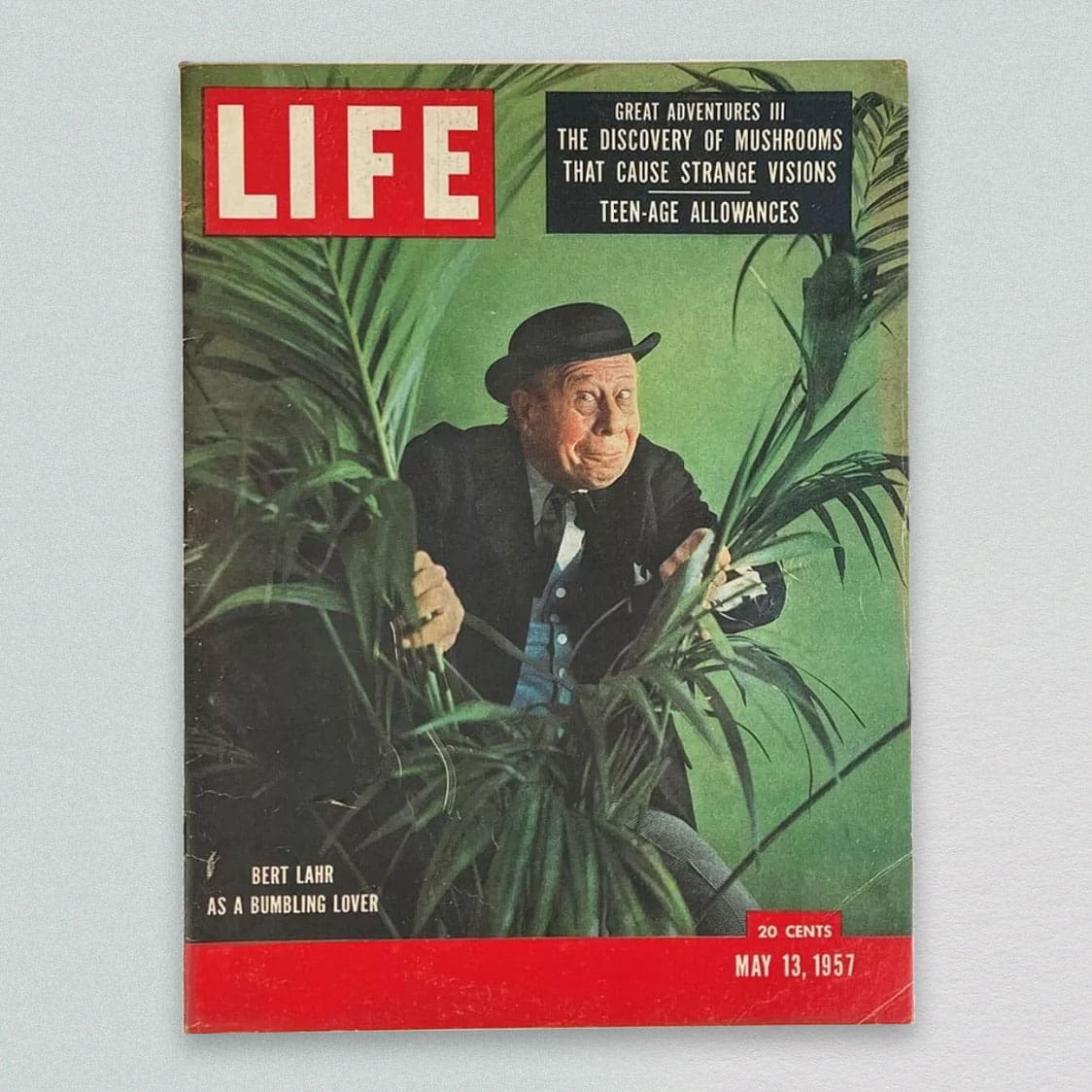

She namechecks R Gordon Wasson: author of an infamous 1957 photo essay in Life magazine called, ‘Seeking The Magic Mushroom’, which portrayed his experience using magic mushrooms (aka psilocybin) in Mexico’s Sierra Madre Oriental Mountains. Michael Pollan, author of How To Change Your Mind (2018), writes that Wasson’s story was published when “psilocybin mushrooms first came to the attention of western medicine (and popular culture)”. It made María Sabina – the curandera, or healer, who facilitated Wasson’s experience – a quasi-messianic figure within western psychedelic culture, with the subsequent colonising of both she and Huautla, her village, a progenitor for the tension between western psychedelic culture and the countries these ancient substances hail from.

Also of note is the Beat writer William Burroughs. His travels through South America, Tangiers, Europe and the mind in the 1950s and 1960s brought the concept of drug tourism to a wider audience.

Amsterdam’s mixed experience

Known as the ‘City Of Sin’, Amsterdam’s reputation is partly rooted in its famous coffeeshops, where visitors can buy cannabis, hash, pre-rolled joints and edibles over the counter, and smoke at the venue. This is thanks to a 1976 law that effectively decriminalised the personal possession and use of cannabis, while tolerating the existence of outlets selling low volumes of marijuana.

In the near 50 years since this policy was passed, the influence of other illegal psychoactive substances has risen. Most notable of these is cocaine and other substances peddled by the drug dealers that stalk tourists in the city centre’s liveliest streets. The illegal industry selling these drugs has grown so large that the Netherlands is sometimes labelled a ‘narco state 2.0’.

There have been attempts to address Amsterdam’s reputation among those visitors looking for debauchery. In 2023, online adverts were produced telling tourists seeking a “messy night” to stay away. Amsterdam mayor Femke Halsema also tried to introduce laws that would ban tourists from coffeeshops, and relocate sex workers in the Red Light District – the criss-cross of canals and crimson windows that often attracts the most rowdy tourists. The former was voted down by the city council – though it’s now illegal to smoke weed on the Red Light District’s streets and the district’s bars have an earlier Friday and Saturday 2AM closing time – while the latter has, thus far, stalled among protests.

“Cannabis isn’t our problem. Stoned people aren’t generally prone to antisocial behaviour,” says Freek Wallagh, Amsterdam’s night mayor. “If I could get rid of one thing, it would be the British stag parties. The people that don’t respect their limits or the fact Amsterdam is a home to many people.”

Amsterdam certainly isn’t alone in being a destination of choice for the dopamine-drained drug tourist in search of hedonism. Sociologist Tim Turner memorably described Ibiza as an “adult-only ‘drug theme park”, a sentiment the residents of Prague, Tulum, Barcelona and Bogota would also likely empathise with.

Wallagh thinks the 1976 laws are outdated as they, by design, mean that coffeeshops have to buy their cannabis from illegal sources and criminal gangs. It is heartening, therefore, that the Netherlands is undergoing a trial that explores full legalisation, which would mean coffeeshop owners purchasing weed from government-approved farms instead.

Wallagh says that, ultimately, there are too many tourists in a concentrated area, “but I would hate to put up a wall, or for our city to become more conservative,” he makes clear. “Amsterdam is at its best when people come here to experiment, discover a new way to live, and try things with the people they love. I recently spoke to a British couple who were in their seventies, and had come to Amsterdam together to smoke weed for the first time. I think that’s a beautiful thing.”

Health versus harm

In 2010 a famous article in The Lancet ranked the dangers of 20 drugs. Top of the pile, above crack and heroin, was alcohol – estimated to be 3.5 times as harmful as cannabis. It probably bodes well, therefore, that countries are changing their cannabis laws in tandem with further research into its positive effects on everything from seizures to insomnia.

Thailand decriminalised cannabis in 2022 and there have been more than 9,500 weed-based premises opening since, though this “pandemonium” of growth has led newly elected Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawat to propose updated legislation. As it stands – with it still being draft legislation – the changes will enact medical legalisation and a form of decriminalised or tolerated recreational use, but make growing, selling and exporting subject to much tighter regulations.

In Europe, Germany is the first G7 country to legalise growth and possession, as they attempt to curb both the black market’s growth and the negative effect of high strength or impure street cannabis on young people’s health. There remains a desire to avoid an Amsterdam-style influx, however, with Julius Arnegger from the German Institute for Tourism Research telling National Geographic: “Politicians in favour of liberalisation of cannabis are keen to explain there will be no cannabis tourism as a result of the [proposed] new law.”

In the US, cannabis is federally illegal (for now), but a patchwork of laws means the vast majority of states have some form of regulation or decriminalisation. While trepidation has existed – especially among banks and larger insurance brokers – regarding an industry that could, in theory, be nixed at any time, the tourist cannabis dollar is being widely embraced with businesses and state tourist office offering tours to cannabis sights such as Oakland Cannabis Trail or the Colorado Cannabis Tour.

Brian Applegarth, founder of the US-based Cannabis Travel Association International, a non-profit that advocates for the mainstream adoption and integration of cannabis-related travel, said that, “by 2025, 50 per cent of travellers in the US are going to be millennials. And their relationship to cannabis consumption is extremely normalised compared to the stigmatised industry leaders of today.”

Retreats on the rise

Since the mid-2010s, a steady stream of research into the potential mental health benefits of psilocybin and other substances like MDMA, DMT, LSD and ketamine has taken place under the somewhat cliched banner of the ‘psychedelic renaissance’. While ketamine is the only drug to have achieved FDA approval in the US, successful trials have been carried out with psilocybin in regards to secondary depression, end-of-life anxiety and addiction.

Val-Pierre Genton is the senior vice president of growth at Beckley Retreats, which has taken more than 500 people on luxury breaks that include psilocybin “ceremonies” in the Netherlands or Jamaica. He tells me they have three main guest types. “First: wellness transformation seekers, who are usually female, typically professionals, and roughly 31 to 50 years old,” he says. “Then there’s the ‘exploratory mindset professional’, who are typically males in their thirties or forties working in finance, tech or the creative industries. The third type is reflective retirees, who are generally 51 to 75 years old and looking to find purpose in their golden years.”

According to data published by the psychedelic retreat platform Retreat Guru, the quarterly revenue generated by its listed retreats increased from 1.6m USD in the first quarter of 2019 to 5.1m USD by the second quarter of 2023.

Psychedelic retreats are mostly found in the Americas (Peru and Costa Rica reportedly have the highest proliferation, with the former legalising ayahuasca and the latter effectively decriminalising personal drug use); the Netherlands (where psychedelic truffles are legal), and Jamaica (which has no law regarding psilocybin). North America – where ketamine is legal for medical use – also has a booming underground industry, with practitioners increasingly working in plain sight.

In Mexico, common substances are ayahuasca, psilocybin and ibogaine. The latter is frequently used to treat addictions, though considered more physiologically dangerous than other psychedelics due to its propensity to slow heart rate – with a death at Cancun’s Beond ibogaine clinic the subject of a recent Rolling Stone article by journalist Mattha Busby.

Stories about what Marlene Dobkin deRios once termed “charlatan psychiatry” (read: dodgy shamans) are legion in this field, with numerous allegations of abuses of power levelled at notorious figures in the field making for painful reading. When asked if he thinks there should be some kind of regulation of the industry, Genton agrees, outlining Beckley Retreats’ minutely designed protocol that other destinations – that perhaps don’t have Beckley’s experience and funding – might not be able to match. Here, each participant supplies their medical records before taking part in intensive preparation work before the retreat, and integration work afterwards.

Beckley Retreats is an arm of the Beckley Foundation, which was set up 25 years ago by Amanda Fielding – often called the ‘Queen of Consciousness’ or ‘Countess of Psychedelic Science’ in media profiles – and has funded innumerable books, research and policy papers on the positive potential of psychedelics. “Amanda realised there was one part of this that was learning from modern science and one that is learning from indigenous wisdom traditions. We built a programme that honours both,” says Genton. “There is sometimes a sense of appropriation within the psychedelic renaissance, and pretending we’re discovering things that have been in use for millennia.”

The future of drug tourism

Dr Bia Labate, a scholar in psychedelic practices and indigenous cultures, has posed the following question: “How can we ensure the local communities are being respected and are getting something positive in return, not only financially but in terms of opportunities to expand their networks and raise awareness about their needs and aims?” By way of response, a recent study by an indigenous-led group was published in The Lancet, which established eight guiding principles for western practitioners and researchers: reverence, respect, responsibility, relevance, regulation, reparation, restoration and reconciliation.

There is a current vein of unpredictability running through the psychedelics industry, as inflow funding for companies researching psychedelics reduced by 90 per cent (to 37.5m USD) from the first quarter of 2024 to quarter three. This can be attributed to a composite of factors, including the FDA’s recent rejection of MDMA as a PTSD treatment, the collapse of Field Trip – the US’s biggest provider of ketamine treatment centres – and ongoing concerns about the often exorbitant costs of psilocybin therapy.

How this affects the future of drug tourism remains to be seen. But many countries’ evolution of liberalised drug laws – and a global wellness tourism industry that’s worth 651bn USD annually and forecasted to grow by 16.7 per cent by 2027 – ensures that, at least for those that can afford the plane or train fare, getting high on holiday remains a priority for today’s travellers.

“I think, generally, drugs are a good way to the heart of a culture,” Mike Jay, drug historian and writer of High Society tells me. “People often have that idea with food: that if you want to understand how a culture ticks, go into the kitchen. The same applies with drugs. If you want to get into more private or ceremonial spaces, follow the drug thread.”