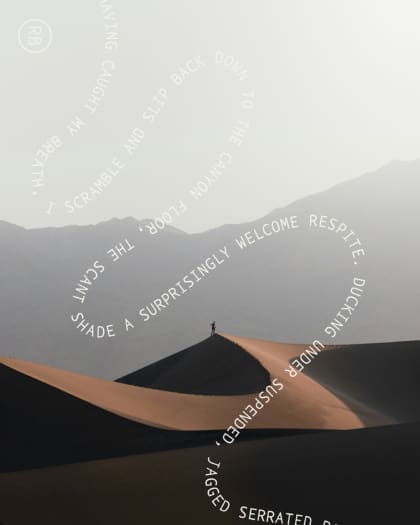

In Motion: Trail running in Death Valley, US

We hit the ground running in the hottest place on earth, uncovering the shifting vistas and dramatic details of Death Valley’s seemingly barren landscapes

I exhale hard, my calves burning as I lean forward, pushing through my heels as I round the hairpin bend. The final incline rises to the top of Red Cathedral. Lips parted, I inhale the heavy, arid air and heave up the remaining few feet onto the ridge. Standing on the narrow summit, the ground drops beyond my feet, jagged ridges rippling away to meet the wide open plain of Death Valley National Park. The desert stretches out without interruption hundreds of metres below, the only visible feature the contours of the sun-scorched earth.

I’m a mere 287 metres above sea level, but atop Red Cathedral, on the cusp of Death Valley’s desert basin, the elevation is exhilarating. The lowest place in North America, Death Valley is a land of extremes, which sees its rocky peaks frosted with snow in winter, and stark desert baked by the blazing sun in the summer months. The largest designated National Park wilderness in the United States is also one of its most remote, with 120 miles separating it from the nearest city, and only a handful of tarmac roads to reach it. The ethereal landscape still feels astonishingly untouched.

Having caught my breath, I scramble and slip down to the canyon floor, the scant shade a surprising respite. Ducking under suspended, serrated rocks, I race along the canyon’s rocky bottom, my feet pounding the natural trail between the gully walls back to Red Cathedral Junction. The path narrows between towering chalky rocks and starts to ascend. I dart into the fissure and feel the stifling warmth between the encroaching walls.

Traversing Death Valley

Running through Death Valley seems, at first, a laughable idea. It’s here that the hottest ambient temperature on earth was recorded (56.7C), with highs of 54C not uncommon in recent summers. It’s no wonder park alerts urge visitors to drink water, stay inside after 10am, and “travel prepared to survive”. And yet each July, when temperatures are at their most extreme, up to 100 ambitious runners tackle the Badwater Ultramarathon – a 135-mile road race through the valley.

Starting from the salt flats of Badwater Basin, 85 metres below sea level, the route rises along Badwater Road to the highway, over the Paramint Mountain Range and into Lone Pine, before summiting the lofty heights of Mount Whitney at 2,530 metres. Dubbed the toughest footrace on earth, it’s not for the fainthearted, featuring over 4,450 metres of vertical ascent. This year, of 97 ambitious starters, 74 completed the route.

While not quite ready to tackle such extremes, at four kilometres into my gentle 10k loop, I can see why runners and hikers are captivated by this shifting landscape. In the shade of the canyon on a pleasant spring day, the heat is still a constant companion. As I hug the slopes of Manly Beacon, the terrain changes once again. Chalky white gives way to a worn trail of undulating ochre. The Valley’s geology is renowned, with dynamic shifts in wind, water and plate tectonics shaping its wrinkled surface. Research is an ongoing process, revealing a world of ash beds, volcanic debris and lava flows meeting to limestone, mud, quartz, and a wealth of fossils – a rich history hidden in the seemingly barren landscape.

Standing at the windswept crest of Manly Beacon, 246 metres above sea level, the towering Zabriskie Point draws the eye ahead. Turning momentarily, the smooth ribbons of rock carry seamlessly down to the Death Valley basin. In this unsettling landscape of bare rock and beating sun, without a wisp of greenery to soften the harsh terrain, the minutiae becomes overwhelming. The variety of stone – colours and texture, beaten by weather and time, with grains and granules, pebbles and boulders. It’s timeless and ancient, and somehow immediate, the present inescapable as I race to escape the sun; hot (but happy) in an unknowable maze of gullied canyons.

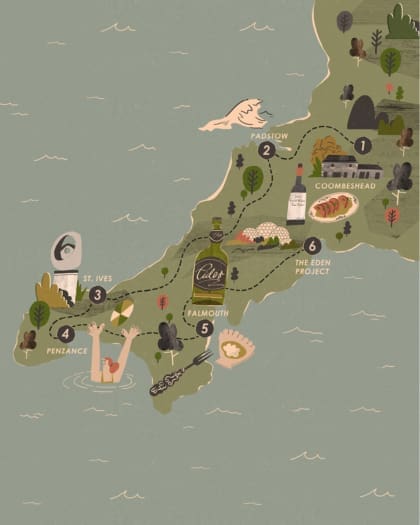

I take another sip from my flask and find it nearly empty already; the arid air is deceitful and whips sweat from my temple before it forms. The lack of humidity is a dangerous adversary in such an unforgiving landscape. Even the place names here are a heady mix of cautionary and evocative. My starting point, ‘Furnace Creek’ on Badwater Road, acknowledges its dichotomy. My route continues on through Golden Canyon, climbs Red Cathedral, and treads the Gower Gulch Trails, before finally tackling the ominous-sounding Badlands.

Before I know it, I’m tumbling downhill, legs spinning to hit the Badlands at pace. The trail changes again, solid rock giving way to shifting sand and smooth pebbles beneath my feet as I follow the creek, a dehydrated riverbed which, when flash floods fall, is submerged in the torrent. Here, the soft sedimentary rocks have succumbed to the water, widening in its path to meander back toward the valley, a contrast to the deep funnels in the bedrock found elsewhere in this warren.

Emerging from the ravine, I sail down the final track to rejoin the Valley floor. As I race alongside the cracked road, epic rock formations rear to my right, while dust and sand stretch out unending to the left. I am an irrelevant speck in the landscape; the scale of the desert inconceivable, completely without feature or formation to make sense of its expanse.

How and when to visit

Visiting Death Valley is well worth a trip. Unless joining a group tour, it’s best to hire a car and be prepared to put in some miles. Driving from nearby Las Vegas takes a couple of hours, Los Angeles can be done in a day, or set off from San Francisco with a stop or two along the route as part of a longer itinerary. If coming from the west, the drive over the mountains provides exceptional views as you descend into the park, and Mesquite Flat Sand Dunes are well worth a stop on your way down to Furnace Creek.

With only a handful of true roads, the area is easy to navigate, though GPS and phone signal is slim to none, so come prepared with a physical map to pinpoint your preferred stops. Make sure to stop at a visitor centre on your way in to pick up a park permit, and familiarise yourself with the current conditions.

For keen trail runners hoping to experience the otherworldly landscapes of the canyons, winter offers the coolest temperatures, with days averaging a balmy 21C in November and 18C in February. Warmer temperatures from March still offer enjoyable trails, and wildflowers abound from April. Look out for the change in vegetation as you gain elevation, offering a chance to witness the Valley’s awe-inspiring natural features and resilient vegetation.

No matter the time of year, respect for the climate is paramount. For runners and hikers taking to the trails, sun cream, sunglasses, electrolyte tablets and plenty of water should be basic provisions. Water can be purchased at Furnace Creek Visitor Centre or found at all accommodation.

Where to stay

As a relatively isolated National Park, accommodation options within Death Valley are few. The Ranch at Death Valley and The Inn at Death Valley are both located in the central basin by Furnace Creek, and offer something for varying budgets. At The Ranch, there is a range of drinking and dining options and a well-stocked general store with trail snacks, refreshments, and an array of merchandise. There are a handful of campsites within the park boundary, including at Furnace Creek.