Anica Mann of Delhi Houses is capturing the beauty in Delhi’s everyday

Curator, archaeologist and art historian Anica Mann on celebrating Delhi’s mid-century homes through her community page Delhi Houses

Delhi’s extroversion has been widely documented, but as a city, it’s arguably as much a destination for introverts, with its acres of public parks, countless mandirs, and private spaces ripe for solitude.

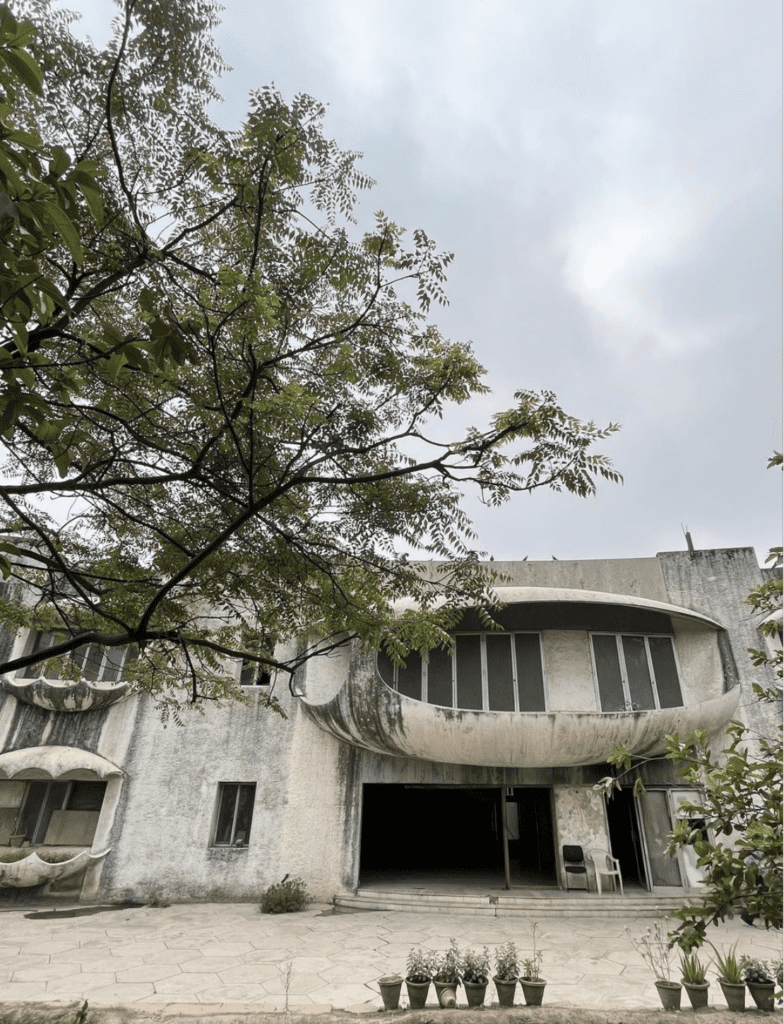

This sense of tranquillity is a quality that Delhi native Anica Mann documents in her project Delhi Houses, an Instagram page that she uses to capture mid-century houses before they’re redeveloped into modern apartments. Born in Jamshedpur in East India, the project started when Mann was visiting Defence Colony in Southeast Delhi and found herself captivated by the light falling on the false walls of a nearby building. From there, the account has grown and become a hub for a passionate community of locals and non-locals, who are drawn to Mann’s eye for detail and poetic, flowing captions that blend historical context, nostalgia, and personal observations.

While Mann’s expertise and visibility as a curator, archaeologist, and art historian (she has curated the Young Collector programme for the previous two editions of India Art Fair) has helped set Delhi Houses apart, she emphasises that she’s part of a much larger movement. That sense of nostalgia and urgency is echoed in similar projects across India, in cities like Kolkata, Mumbai, Hyderabad and numerous others, each of which capture moments in time and reflect on a country that’s changing with incredible momentum.

We caught up with Mann to talk about what it means to be from Delhi, the origins and evolution of Delhi Houses, and why the project has become a paean of sorts to the city’s softer side.

The inspiration behind Delhi Houses

How did the Delhi Houses project begin?

I am a Delhi person. I wasn’t born here – I was born in Jamshedpur, in East India, where my mother is from – but I was raised in Delhi. My dad is from here, my parents went to Delhi University, and I also attended Delhi University. I’ve travelled around the world, but my hometown – my native, as they call it in India – is Delhi. I used to live in the northern part of Delhi; I studied in the southern part. I got the chance to go about the entire city and watch it change over the past 30 years.

What I love about Delhi is that, as the capital, it has various time capsules in it. These are captured well in the big public monuments like the forts, the temples, the old universities, and archaeological sites strewn across the city. During partition, a lot of families left Delhi and went to Pakistan, and lots of families from what is now Pakistan came to Delhi. So, as modern Delhi kept expanding beyond the British zone and the Indian Mughal zone, it grew in pockets. There was a small, gated colony for journalists; another for the police; another for lawyers, for judges. These communities became New Delhi – even on addresses is still called New Delhi to this day. I love exploring these different colonies.

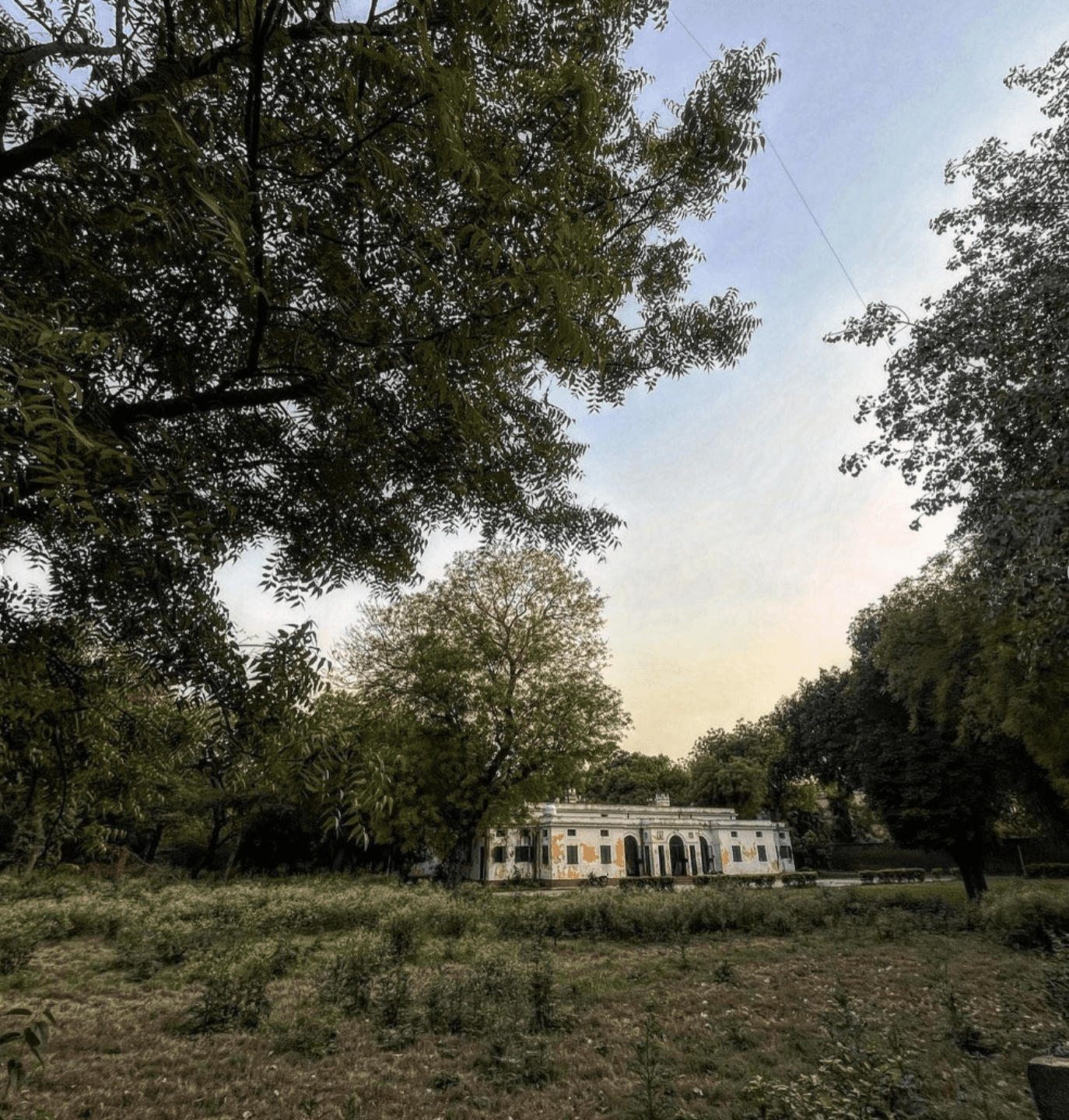

The idea of Delhi Houses is a very soft and nurturing story. Because Delhi is a growing city, I feel that soon its houses will become smaller and smaller and many will disappear altogether. The project started with me wanting to catch the last glimpse of these homes before they disappear, and paying homage to the houses that decided to hold on.

That’s beautiful. What was the process between having that thought and starting Delhi Houses?

The moment I realised I wanted to start Delhi Houses was when I went to see a house in Defence Colony. The light was falling beautifully on it – it looked amazing. It was the very first picture on my Delhi Houses page – a beautiful, modern structure, a tiny glimpse of Guggenheim Modernism in Delhi. It had these lovely false walls that sheltered the interior.

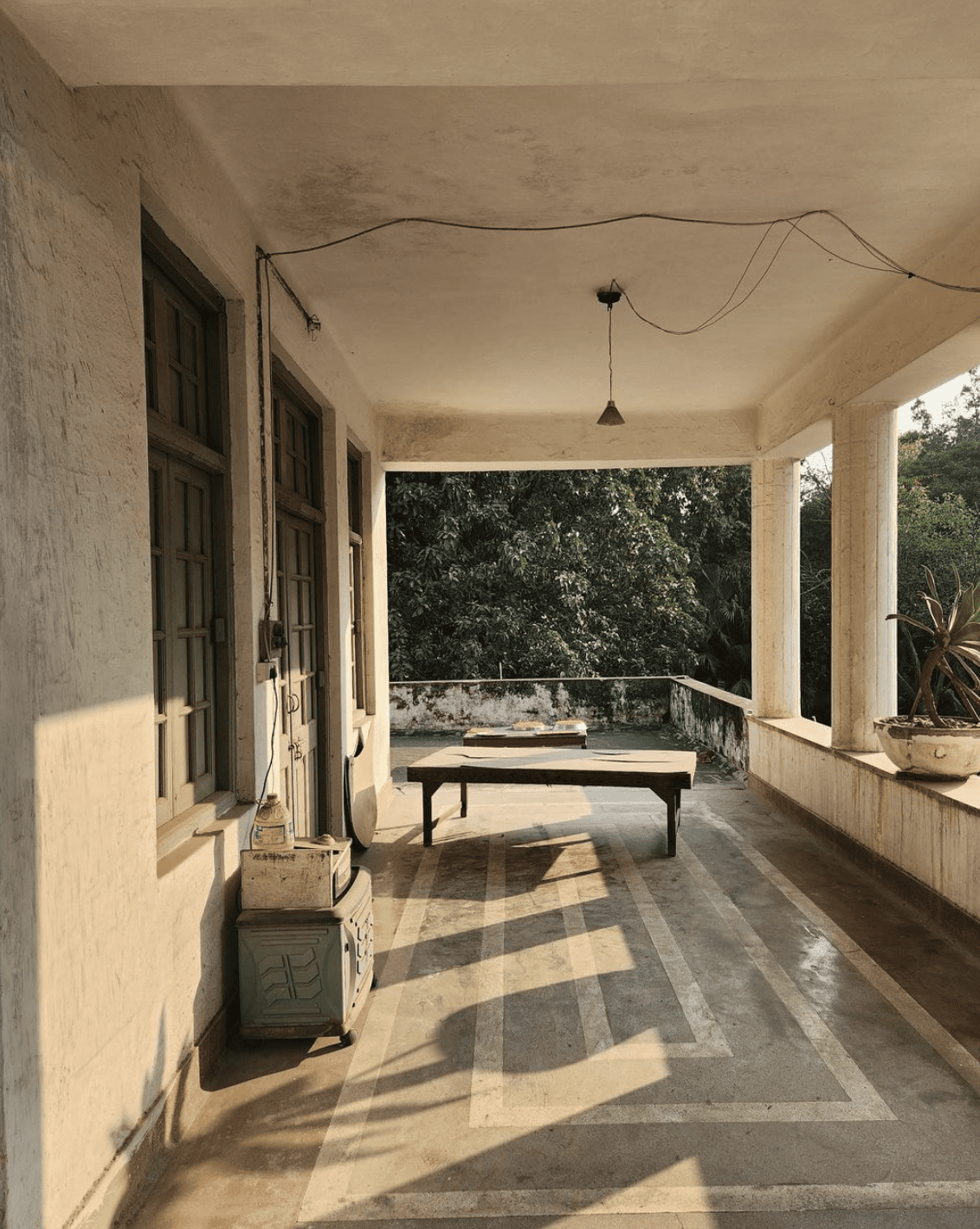

The family showed me around the house, and I realised it was laid out according to the vāstu – the traditional Sanskrit teachings on the optimal layout for a house to provide good energy. When we went to the first floor, I saw their prayer room. They were a Sikh family, and the mother of the family had absolutely maintained that room according to prescription. She sat there reading her religious texts while we quietly looked around respecting her space.

The kitchen opened to an outdoor courtyard, which was typically used for the preparation of food. Indian cooking produces so many fumes, so many smells – it’s just an explosion. Some food just needs to be cooked outside! The courtyard had an old well, which tend to only exist in pre-1950s houses. These glimpses of this home made me first want to capture them in photos.

Around the same time, my friend Umah Jacob, director of external relations at India Art Fair, who is from Bombay, would visit me in Delhi, and I’d take her around the city, checking out the different colonies of Delhi, getting a snack or some chai somewhere, and dating the different architecture we saw.

Delhi as a city

I love the idea of you both walking around the city drinking chai and dating houses together. Zooming out, how would you describe the city to someone who has never travelled there?

Imagine a deeply ancient city that dates back to pre-history. Since then, it’s been a Muslim capital, a British capital, a Hindu area. Right in the centre of the city is an old fort on top of a mound. It is a city full of people, full of houses that they built over time, and history is everywhere you look. Even some trees are historic trees.

But with all that history, why document homes that aren’t that old?

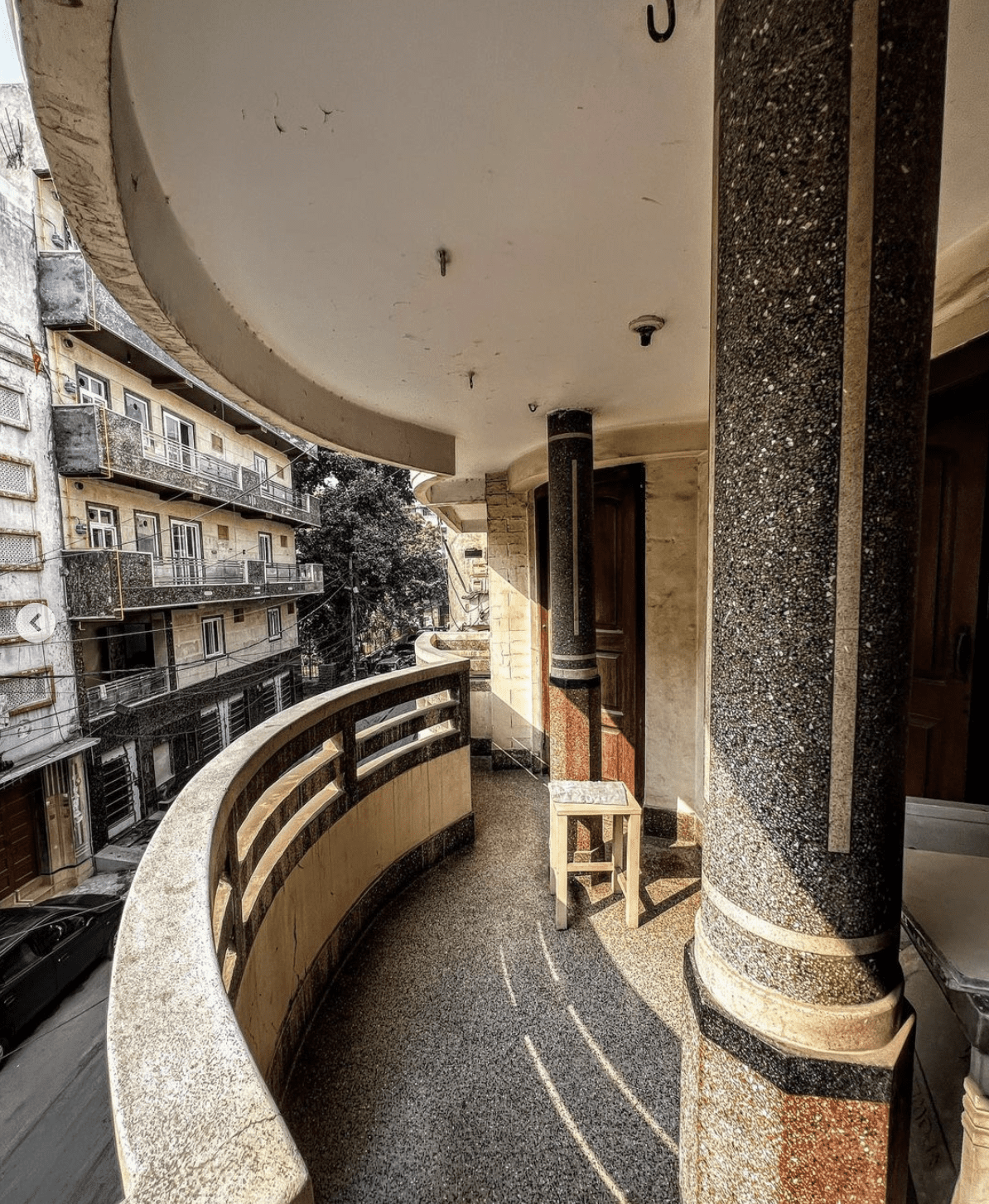

My personal interest lies in trying to understand how independent India came about, how formal civil society was launched across the country, and how people have grown together. So those personal spaces from the middle of the century speak to me. I love documenting the unusual, such as a brutalist home, an art deco home, or a home with very ornate or baroque verandas. People were settling into their new lives in independent India within these homes.

Before Delhi Houses, there was a page called Calcutta Houses, and there’s now Pune Homes, Delhi Houses, Chandigarh Homes, Houses of Bengaluru, Hyderabad – everywhere. It’s a small community of people taking photos of homes before they disappear. They tend to look at a short time period, because India was built very fast and very functionally. The houses were not meant to last – they have a set time period.

There’s a collective sense of urgency to celebrate these lovely houses that remind us of the start of independent India, and require serious attention and refurbishment. We might be the last generation who get to see them.

What has the response been to Delhi Houses? What do you sense it means to people?

The response has been wonderful. I didn’t really discuss it, I just did it – and there’s been a very sustained interest. People were talking and started opening up their houses, so that was wonderful. And the community has grown since. It’s not a page that posts every day or has any sort of business interest. It’s a photo album with captions.

A lot of people mistake it for a real estate page. I get a lot of requests from people – ‘Oh, I want to do a shoot there.’ I always reply very respectfully to them, ‘I’m so sorry but it’s a private home. I cannot reveal the person or location.’ And generally, when I post things, I tend to put a general location and neighbourhood because at the end of the day, it’s someone’s home.

So do people reach out to you to invite you into their homes?

Yes, frequently. And I’m picky about what homes. At some point in the early 2000s, a new regulation stated that all houses had to be built on stilts, so that cars could be parked away from the clogged roads. Now all the houses look the same. Whenever people invite me to see a stilt house, I tell them their house has a lot of life left in it still. They’re not in danger yet.

Architectural features of Delhi houses

We talked about how in Delhi, the house is a negotiation between the architect, the borough, and the contractor, and then any other conventions or traditions. Are there any features that you look for, and is there a style of house that you gravitate towards?

Delhi has several constructional movements. It had its red brick moment; it had a white brick moment; it had a period of modernist light blocking, cladding; it had a false ceiling moment. The light switches changed somewhere from very antique looking to very modern looking. I love houses from the 50s, 60s, and 70s. And in older parts of Delhi, the traditional Havelis with the courtyard and the rooms surrounding it. I love rooftops that are used as a kitchen – I especially seek those out. I love barsaatis – the classic old bachelor pad rooftop Delhi penthouses.

I love a house that is being lived in. Or a house that is abandoned because of a legal dispute or a pending family settlement, when they are completely sealed off. It’s interesting to capture what kind of life houses live when left to themselves.

Is there a particular time you like to go?

I love going out early in the morning and catching the sunrise. It’s made me a much healthier person. All the photos are taken by me, and I write all the captions. I love sitting down with my morning coffee and recalling what I was feeling at the time when I was seeing that house.

Are there any guidelines you like to follow?

I have certain rules that guide me when taking these photographs. I think it’s ok to take a photograph of a house from a public road. You shouldn’t be climbing a wall into a garden or anything like that – just from the road, the view the public can already see.

But when I’m invited inside, I share the final selection and the write-up with the person who invited me before publishing. I remove whatever they request, no questions asked. When I follow these simple rules, I feel like I’m in a good place and that everyone is participating.

The future of Delhi

For you, given the continual change and turnover in a city like Delhi, has the city’s architecture become too disposable?

It has. For a country like India that is always growing so quickly, the architecture around us is indeed disposable. I don’t know much about the construction industry, but I feel that there was so much personal character before to identify homes, but now, all homes look the same. And it’s becoming a more expensive city to live in – people don’t live in bungalows or townhouses anymore – apartments are more common.

With this level of hustle and work and quick turnaround in India, the architecture is becoming extremely disposable. People love decor, but they don’t get attached to their homes. Furniture, crockery and wall colour change every six or seven years. I lived in Japan for a while – there, they have a superstition that you shouldn’t hold onto things for too long, because gradually they become possessed with their own identity and spirit. So there’s a fantastic infrastructure of second hand stores and markets, because once the thing changes hands, it loses that character and starts taking on another.

We don’t have the kind of infrastructure in India necessary for the disposable level we’re living at. People are making things that are easily breakable. There’s no architectural style and there’s no story that the city is telling any more through its homes. That’s what I feel really sad about.

To you, what does the project say about the city?

If you are Indian, you would understand that Delhi is a very ‘rude’ city. It’s always flaunting its connections because it’s the political capital; it’s always a bit irreverent. I hope this page shows the softness of the city and the homes that the people who live here occupy.