How sustainable design is transforming the hotel sector

While sustainable initiatives in various forms are now frequently found throughout the hospitality sector, how has a drive to net-zero impacted hotel design? Introducing the planet-friendly pioneers of the architecture and interiors world.

Whether it’s a Greek island idyll carved into rock for subterranean insulation, a Danish hotel constructed entirely from carbon capturing wood or a city-centre period property whose interiors utilise upcycled materials, the understanding of what constitutes a sustainable hotel is changing. Forget a ban on plastic bottles or a note about limiting laundry: as travellers become more aware of greenwashing and the climate crisis, it’s increasingly a hotel’s design rather than its day-to-day operations that are being called into question.

And rightly so, given the environmental impact of construction. “The building industry adds more carbon to the atmosphere than any form of transportation,” says architect Bill Bensley, a champion of sustainability in the hotel industry. As per his Sensible Sustainable Solutions report, the construction sector alone contributes 23 per cent of global air pollution, 40 per cent of drinking water pollution and 50 per cent of landfill waste.

“Sustainable design, in my mind, is just common sense,” Bensley says. “I don’t pound the eco drum with any of my clients as they would fear extra costs. I just design sensibly, with all the respect in the world for Mother Nature.”

Rethinking materials

It all starts with the approach to materials. “I am a proponent of alternative building methods,” says Bensley. Concrete is the second most widely used material in the world after water. If it was a country, it would be the third largest carbon emitter in the world. Steel manufacturing is also one of the most carbon-emitting manufacturing processes. Finding alternative materials to concrete and steel is therefore key. Depending on the design brief and location, Bensley suggests alternatives such as bamboo (a regenerative and fast growing tree), cork (also a renewable resource, as trees are not felled when the material is harvested) and Ferrock (a carbon-negative cement-like binding material).

Using wood in an innovative way is also becoming a popular alternative. Cross-laminated timber (CLT) – a regenerative material as strong as steel – has been shown to store and capture additional carbon when used in construction, much like it did in its previous life as a tree. On the Danish island of Bornholm, architecture studio 3XN built the first full timber hotel from CLT at Hotel GSH. While at Wood Hotel Bodø, a new outdoor resort in Northern Norway, the buildings are made from sustainable timber from Moelven, a company using a pioneering approach that ensures every part of the tree is used to its full potential in order to maximise the resources of the forest.

Extending the life cycle

However, using what already exists in new and interesting ways is almost always the least carbon-intensive option. This rings especially true with repurposing period buildings – something Helena Toresson, vice president at Wingårdhs architecture firm, knows well. She was recently tasked with the interior architecture at the new Nobis Hotel Palma, which occupies a 12th-century building that had been unoccupied for 30 years. “We always want to keep as much as possible of the original building,” Toresson says. Seven years in the making, the original sandstone arches, wooden ceilings and brick walls purposely left unpainted are seen throughout. When new materials are needed, durability is the number one priority to ensure the building’s ongoing preservation. “The best way to build sustainably is making things that last,” Toresson says.

Ricardo Larriera, founder of Gundari, a new sustainably led hotel on the small Greek island of Folegandros, also takes this approach. Gundari’s site is sitting on masses of marble and stone that provided 80 per cent of the materials required for building the hotel’s walls. Half the buildings are subterranean, giving a high level of insulation that eschews the need for energy-intensive air conditioning – crucial as the Mediterranean’s summers continue to increase in temperature.

Circular interior design

For Toresson, interiors are all about balance as deciding between new and second-hand pieces can prove tricky. A mix of both is the most sustainable, opting for new pieces for things that sustain a lot of wear, such as beds and sofas, and sourcing second-hand for decorative pieces. The goal of creating something that lasts always prevails. “We want to create something relevant, not trendy,” she adds.

Thinking outside the box when choosing furnishings is also important, as seen clearly at Queen’s Gardens – Inhabit’s latest property in Bayswater, London. Designed by Holland Harvey Architects, the Grade II-listed Victorian townhouse was decorated with Ege carpets made from recycled fishing nets while the terrazzo mantelpiece in the lobby was crafted from rubble from the build. They also prioritised working with social enterprises to ensure a positive impact for people in the community – an important element of sustainability that is sometimes overlooked.

The goal of creating something that lasts always prevails. We want to create something relevant, not trendy

Goldfinger, which works with young offenders and at-risk youth, created bespoke furniture using responsibly sourced timber across the hotel. At newly opened JAM Lisbon, interior architect Lionel Jadot made community a key part of the project, too, working with local craftspeople and sourcing all materials from within a 100 kilometre radius of the hotel. Porto-based Flowco’s tile headboards had a previous life as shoe soles while lamps are made out of recycled bricks recovered from local construction sites.

Bensley echoes these ideas proposing renovated antique doors, recycled glass tiles or second-hand denim insulation. At this year’s Milan Design Week, reinvention of materials was a big theme – see JC Architecture’s Bloom chair crafted from a meat by-product called Kobe Leather and Hydro’s 100R exhibit using the world’s first recycled aluminium entirely from post-consumer scrap – illustrating how this thinking is very much here to stay.

Working with nature

For new hotels built within nature, many are going beyond just respecting the land but actively trying to improve it through design. “I want to make sure that biodiversity in the local area improves year on year,” Larriera says of Folegandros. Before construction started, more than 600 indigenous seedlings were collected from the property’s 80 acres, which have since been returned to regenerate the land. Located at an important point for migrating birds between Europe and Africa (soon to be named a biosphere nature reserve) the land is also being overseen by a bird monitoring conservation programme.

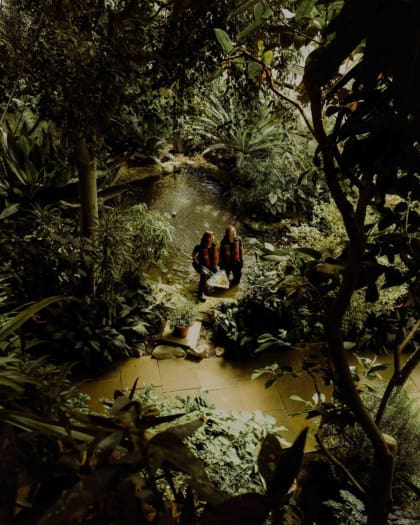

This is also something Louis Thompson, founder of Nomadic Resorts, feels strongly about. Alongside sustainable hotel projects, Nomadic Resorts is known for its tented pods made from recyclable fabrics and bamboo flooring, offering the comfort of a luxury hotel room within a back-to-nature experience. With these projects, regenerative landscape design is crucial, something Thompson has seen come on leaps and bounds since he started his company in 2012. “The technical side of rewilding has improved significantly,” Thompson says. This isn’t just benefitting the wildlife and ecosystems but the experience for travellers, too. “At Wild Coast Tented Lodge in Sri Lanka we created waterholes so the animals came to the camp,” he adds.

A green future

Looking forward, Thompson is positive about upcoming developments across sustainable building design. “We are working with ongoing research into new green roof structures. There is exciting innovation in this area on how you can push the limits of building materials made from growing plants,” he says. Beyond this, the biggest change he predicts relates to the sustainable operations of hotels. “The cost of solar power is falling and soon renewable energy is going to be cheaper per hour than fossil fuels.” However, what’s set to make a huge change to this area is artificial intelligence. “AI is going to be really useful in how to improve performance of renewable energy systems,” he adds.

The biggest roadblock to the roll out of sustainable hotel design is cost. While in the long term the cost of running a sustainable hotel is always less, the initial build is more expensive. Subsequently, the biggest innovations often occur in the luxury market. This is why sharing information is so vital – something that Bill Bensley’s open source white paper, which is full of useful and inspiring information, speaks to.

As these ideas spread, future hotel stays are set to look a little different. Across the board, biophilic design will lead the way with buildings and their interiors coming closer to nature. More obvious iterations could mean you’re sleeping in a luxurious tent in the wilderness, a beachside bamboo structure or in a suite built from living walls while – on a more subtle scale – you’ll see more period properties revived and once forgotten objects and materials given a new home and life.