Focal Point: Street photographer Sam Ferris on Sydney

Lauded street photographer Sam Ferris fell in love with Sydney when he began photographing it. He shares his unique view of the Australian city

“I walk the Sydney streets to discover and make candid photos of our times, in public places, that are un-staged, unmediated, and representative of not only what I see but also of what I feel — my emotional experiences of the world,” says Sydney-based photographer Sam Ferris.

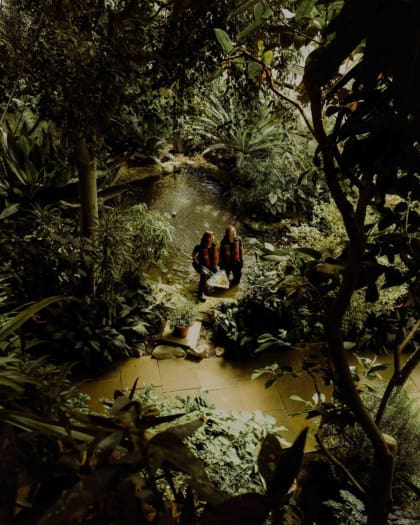

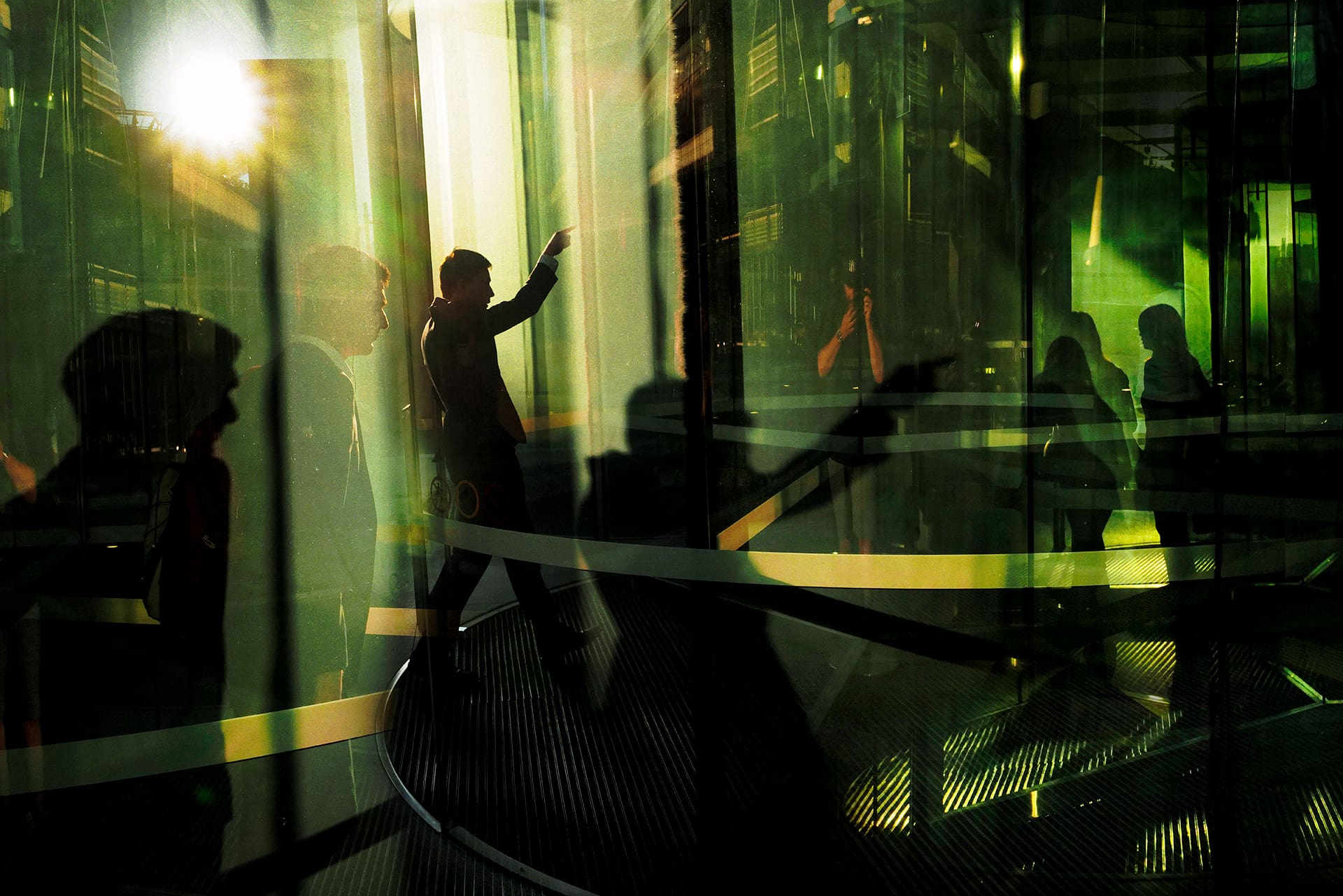

His eye-catching street photography captures expressive moments between people and their environment, and the interplay of multiple light sources with geometric forms – and has seen him named Australasia’s top emerging photographer in 2019 in the category of documentary photojournalism, along many other accolades.

Ferris’s love of photography began early – his mum gave him a camera when he was just seven, while his father is a painter, which influenced his creative path: “Long before I had any idea that there was even such a thing as ‘street photography’, I had been absorbing the visual language of art,” he says.

In 2021, Ferris published his first monograph, In Visible Light, which is a culmination of ten years of his street photography in Sydney, and is now in its third print run. He also co-founded AUSSIE STREET – Australia’s international street photography festival, which is returning this year after two years of pandemic disruption.

But taking photos is more than a creative practice: “Photography and simply spending countless hours on the street has allowed me to connect with Sydney, a city that I initially felt overwhelmed by, and learn to see it as my home,” says Ferris. “I now find that the light that originally made me feel exposed while walking through the city is able to reflect my perceptions of the beauty, struggle and strangeness of everyday life. I’m able to represent the world around me in a way that I feel reflects my experiences of life in this time, in this place.”

The photographer shares how he first became immersed in photography, how his love for it evolved, and how he goes about capturing his atmospheric images.

When did your photography practise become more serious?

It was when I was working and researching at university five to six days a week. I was fairly miserable and under a lot of stress. In order to get outside and have a break from my desk, I set about walking to and from the campus and home, which took about an hour and a half each way.

On these walks, I began to notice things. After a while, I brought a compact point-and-shoot camera with me to photograph along the way. I would often change my walking route because I enjoyed the feeling of being lost in suburbia. This led me through Sydney’s stark industrial areas.

There were streets of factories, warehouses; the skeletal remnants of abandoned buildings, construction sites; all machinery, wire, and concrete. I found these areas interesting to photograph because of the alienation I felt walking through them; an environment so bleak and devoid of humanity. It reflected back how I was feeling at the time. I didn’t do anything with these pictures but they felt good, like I was doing something.

What subjects inspire you?

I look for light and shadow, colours, oddness, the uncanny, symbolism, and the interplay between people and the environment they’re immersed in, but perhaps not aware of. I’m always attracted to streets and corners with multiple light sources: direct from the sun, and reflected from buildings, windows and glass for layers and reflections.

I also experiment a lot, with a very high failure rate, photographing through windows or multiple layers of glass to achieve a surreal, multifaceted picture, that captures the oftentimes overwhelming nature of the city. I try not to overthink things when I am photographing in the moment; I follow my intuition and then analyse the results later when editing.

Can you describe your process in capturing a photo?

I tend to be drawn to a scene or setting first and then hover around it, waiting for elements to come together. I experiment, observe, and try to be prepared so that if there is a picture to be made, I’ll be ready for it. I’ll follow my instincts and shoot first, then ask myself if the pictures are interesting, revealing or meaningful later. I work full time and have a young family, so time is a precious resource.

Usually, I only have a short window to make pictures. I know the city well enough that I have a good understanding of where to be and when in order to put myself in the best possible position to make interesting photographs. Sometimes I’ll only have 15 minutes – especially in the winter months when the days are far shorter, so I have to make those minutes count. I plan my route and know where I’m going in these situations. Other days when I have more time, I like to explore and seek out new scenes and locations in which I haven’t made images before.

When in the act of taking a picture, I don’t try and hide what I’m doing: I use the viewfinder to compose at my eye, rather than trying to be surreptitious and ‘hip-shoot’ using the screen on the back of the camera. A lot of people shoot this way now, but to me, it feels a bit creepy. In the way I move and photograph, I feel like I’m invisible most of the time. I try to approach subjects in the way I’d like to be approached myself, in an open and respectful manner. Some photos are worth it and some are not. After about ten years, I’ve got a sense of what I’m comfortable taking and what I’d rather let pass by without raising the camera.

Do you take a different approach when photographing different subject matter?

In terms of what I’m looking for – a moment of connection, emotion, gesture – it’s very similar. The way I approach photography is with curiosity and without pretension; like that sardonic but telling line by American street photographer Garry Winogrand, I want to see what things look like when photographed. When photographing family, there’s an implied consent to the pictures, so in that sense they’re easier to make. I already have access to that level of intimacy. But with it comes the fact that my main role in the family is not ‘photographer’, so there is a limit to the time I can spend making pictures of them.

What have been your photography highlights so far?

Most of what I do results in failure and rejection. The few successes I’ve had are a product of obsessiveness and sheer effort. When my book In Visible Light was rejected by a number of prizes, publishers, contests and festivals – or on the few occasions when it was received positively only for me to be told that because of the ‘high cost’ or ‘financial risk’ associated with producing it, I’d need to front upwards of 20 000 AUD [nearly 14 000 USD] to make it a reality – I became determined to self-publish. So I’d say one highlight from recent times has been backing myself, publishing and printing my book myself and – thankfully – selling out of more than 700 copies in a relatively short time. It’s given me faith that there’s an engaged audience for my work and that it resonates with them.

What do you hope people feel when they experience your work?

Something. Anything. Emotion is hard in photography and very hard to evoke from an audience. Photography allows me to make the world over according to my own specifications – a particular and unmistakable way of seeing and perceiving that’s mine and reflects what I’m inherently drawn to: complex pictures that reveal ephemeral moments of candid emotion. Beauty, stillness, joy, melancholy, loneliness, humour, irony, contemplation, angst and everything in between. In my best images, it’s my world and no other.