My City: Paris

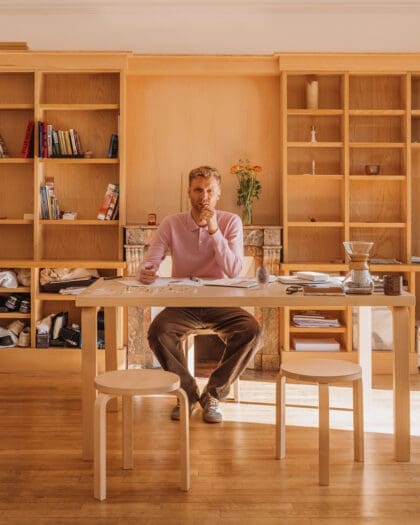

Writer and editor Seb Emina reflects on a decade spent living in Paris, from embracing Gallic stereotypes to discovering the city’s multicultural corners

The rating system of Google Maps goes beyond obvious, well-trodden categories such as hotels, restaurants and hairdressers. Users can, if they want to, check the aggregate rankings and accompanying reviews of mountains (Mount Fuji in Japan: 4.6 stars), deserts (the Sahara Desert: 4.0 stars), and oceans (Pacific Ocean: 3.5 stars, avoid).

This function does not apply to cities, however. Opinions about how good Paris is as a whole are not aggregated, and I think this is a shame. “Paris is a commonplace, a place revisited in fiction, in fantasies; a place you can know without ever having set foot there,” writes Jakuta Alikavazovic in Like a Sky Inside, an account of spending a night alone in the antiquities section of the Louvre. It would be interesting to know how many of Paris’s 30 million yearly visitors are satisfied with their experience versus how many come away feeling disappointed that it was different to the place they’d imagined, the fiction or the fantasy.

I want to say that, given the opportunity, I would write a good review of Paris. To do so would not be very Parisian of me. As Éric Hazan points out in Paris in Turmoil, it is Parisians themselves who are some of the most determined to denigrate the city, usually by lamenting its decline in some way: a tradition that goes back centuries. But that’s OK. Even though I have lived here for around ten years, I will never myself be Parisian. I accept that.

When I moved to Paris from London, I arrived by train, an oversized suitcase trundling around behind me (note that if you need a restaurant opposite the Gare du Nord, you should go to Terminus Nord, as that is the good one. Nearby Les Arlots also comes highly recommended). I then travelled to Luxembourg station in the fifth arrondissement, near the ornate garden with its chess tables and meticulous fountains, and walked from there to the apartment of my then-girlfriend, where I would be moving for an unspecified amount of time. I assumed we would go back to London, eventually.

It was tiny, with a small balcony from which we could see, and be seen from, the flats in the buildings across the street. At one o’clock each afternoon a man in his mid-fifties would emerge from one of them onto his own balcony where he would unfold a picnic table and on it arrange a baguette, a saucisson and a glass of red wine. He would look at us throughout this meal with the demeanour of a regular lunch companion. He wore no clothes above the waist.

"On street corners I’d encounter accordionists interpreting Édith Piaf songs, observed by men and women in Hermès foulards"

The fifth arrondissement is a torchbearer of “classic Paris”. It’s on the Left Bank bordering the Seine and is populated with a cast of quaint markets and art deco cinemas, as well as the Sorbonne, the Panthéon and the Shakespeare and Company bookshop. It’s in the fifth that Michael Fassbender’s hitman waits in a disused office in The Killer, watching a hotel suite through his rifle sight while musing that “Paris awakens unlike any other city – slowly.” It is a pragmatic observation on some level. What are the implications of a quiet morning with respect to the assassination trade? But the film knows the viewer will always appreciate a reflection on Paris for its own sake, a nod to the morass of romanticism that the city generates and is fed by. The fifth is also where Emily lives in Emily in Paris, the TV show that has done so much to refresh that morass and the stereotypes that come with it (handsome chefs, offhand rudeness, blasé infidelity) for the social media age.

With the act of moving here and, worse still, being an English-speaking writer (and quite soon afterwards the editor-in-chief of a literary magazine), came the shame of sailing closer and closer to the wind of cliché. I would sit in laundrettes reading Kierkegaard. I would shop at a grocer who treated tomatoes as a sculptural medium. On street corners I’d encounter accordionists interpreting Édith Piaf songs for the benefit of men and women in Hermès foulards. It was best to simply go with it. When I was out to buy mundane things — toothpaste, a light bulb — I would look up and around and think, “oh that’s nice.”

Not that it was an uncomplicated parade of croissants, air kisses, kir royale and so on. Paris has a big city’s share of traffic, drunks, riots and burglaries. The bohemian dream of the Left Bank wasn’t what it used to be. I’d see men in blazers rifling through rubbish bins: bourgeois poverty was rife. As Hazan describes it, “the old psychoanalysts, the old writers, the last proponents of existentialism”, by which he means the people who have traditionally given the Left Bank its literary reputation, had been forced out by skyrocketing rents, meaning “the book world’s centre of gravity had shifted from the Left Bank to the north-eastern corner of the city.”

Belleville is a different sort of neighbourhood, with dive bars, brutalism and anarchist theatres

After a year or so I moved to Belleville, in that corner of the city, a very different sort of neighbourhood. It’s more multicultural, the site of a Chinatown and Tunisian, Senegalese, Laotian and Algerian communities. There are dive bars and anarchist theatres. There’s brutalism and discount sportswear. There are also some of the best restaurants in the city. Readers are urged to visit Le Cadoret or Le Baratin for classic bistro food, or for a more casual setup try the fried chicken at Gumbo Yaya or the Szechuan dishes at Lim Sept.

In the intervening years I have acquired many of the markers — flat, spouse, child — of being settled, but even so, when people ask, “is that it then? Will you stay forever?” I become agitated, evasive even. The problem is that giving a straight answer risks ruining things. I never decided to stay for ten years. I just didn’t decide not to. “I’ve got no plans to leave,” is what I tend to say. I’ve thought some more about it, and it’s too soon to write that Google review.