How is Patagonia setting the new standard for sustainable business?

When Patagonia announced it was ‘giving away’ its $3 billion company to fight climate change, the news went viral around the world. Its latest headlines certainly mean business – but what does business mean for a company with no owner?

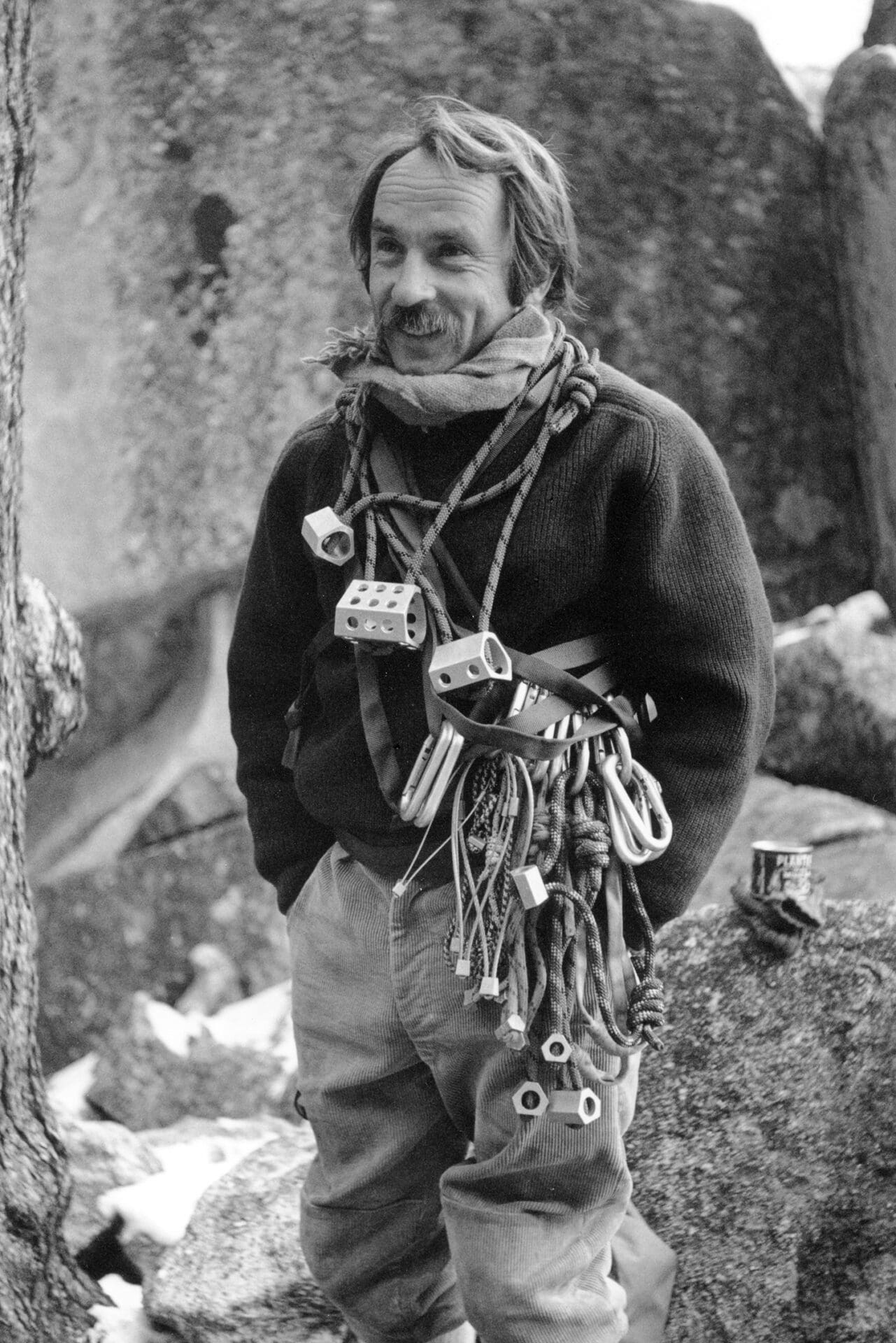

Few brands have stood at the intersection of both travel and conservation, capitalism and environmentalism, quality and cool, philanthropy and fashion quite so stoically as Patagonia. Founded in 1973 in Ventura, California by Yvon Chouinard, Patagonia started out as one man making climbing gear for his mates. Soon, it evolved into the world’s most recognised and successful outdoor apparel company, which to this day sees responsibility for the environment as integral to its very existence: what good is exploring the outdoors, if you’re doing it harm in the process?

Thinking outside the corporate, capitalist box, Chouinard’s ideas have often been called radical, unconventional and revolutionary: Patagonia has offered free repairs on products since the beginning, encouraging customers to reuse rather than buy new; it has provided on-site childcare since 1983, supporting its childbearing employees and those with families; and it took out a full-page ad on Black Friday telling New York Times readers ‘Don’t buy this jacket’ in an attempt to call out overconsumption in 2011. A decade later, it made a record-breaking $10m in sales on Black Friday, and donated 100% of profits to ‘environmental organisations around the world.’ In 2022, the B-Corp certified company announced that their health plans would cover abortion care in the wake of the Supreme Court turning over Roe vs Wade.

As a progressive, purpose-built, circular business model, Patagonia’s is exemplary. It goes beyond PR stunts or marketing campaigns: its people – and the planet – have always come above all else, even profit. This moral compass has enabled the brand to navigate some of the industry’s biggest problems, mapping the way for those that followed it.

So this month, when Yvon Chouinard announced that ‘Earth is now our only shareholder,’ eyebrows were raised throughout the finance, fashion and environmental sectors. Ultimately, the decision means that Patagonia’s actions will focus more on whether the net gain is worth it for the planet, less on pursuing growth; any profit not reinvested into the business would go to tackling the climate crisis, Chouinard explained, and his family were praised for ‘giving away’ the company. In reality, they have handed ownership over to two trusts: all of their voting stock, or the equivalent of 2% in shares, has gone to the Patagonia Purpose Trust, whilst the remaining 98% has been transferred to a not-for-profit organisation called Holdfast Collective.

The funds of the latter will aim to ‘fight the environmental crisis, protect nature and biodiversity, and support thriving communities.’ It can also engage in political campaigns and fund grassroots activists, something that has historically been close to Chouinard’s heart, from vocal campaigns against everything from deforestation and dams to printing ‘Vote the assholes out’ on the underside of labels during a certain climate-denier president’s tenure. We can expect more action that channels that energy in this new chapter of Patagonia’s story.

While details on how the two trusts will work are still vague, Patagonia has a long history of putting its money where its mouth is. The company has frequently used its position to generate change, and Chouinard is that rare species of philanthropist billionaire whose priorities have been clear – and upheld – from the start. ‘Every billionaire is a policy failure,’ CEO Ryan Gellert is fond of saying – and Chouinard famously can’t stand being on rich lists. When Forbes listed Chouinard as a billionaire, he told the New York Times: “It really, really pissed me off. I don’t have $1 billion in the bank. I don’t drive Lexuses.” He sees personal wealth as a problem, and this is his solution.

Beyond the empowering language and stick-it-to-the-man attitude Patagonia has cultivated, it’s the genuinely high-quality products and ageless designs that have generated enduring loyalty amongst its cult following. These are clothes that last so long they go out of fashion and come back in again (see their fleeces from the 90s), and customers are just as likely to be seen stalking Silicon Valley as they are scaling mountains; the Cerro Fitz Roy logo is found on activists, adventurers and tech bros alike.

If it all sounds too good to be true, you wouldn’t be the only one unconvinced that the ripples created by Patagonia’s big splash will have any lasting effect. No matter how ill-fitting the label, Patagonia is part of the fashion industry, the very same that makes one of the largest contributions to the climate crisis – and to its harshest critics, the bottom line is that Patagonia still makes and sells new clothes whilst rallying against consumerism. “There is nothing we can change about making clothing that would have more positive environmental impact than making less,” former CEO Rose Marcario told Wired in 2016, underlining Patagonia’s consistent messaging that less is more. Around two-thirds of its garments are made with recycled materials, though, and in 2019 alone it reported repairing around 56,000 pieces in its North America facility. Every time the company has faced criticism about its supply chain, it has pivoted quickly and effectively to cut out any harmful aspects, re-writing its own rule book to future-proof the process.

The same day Patagonia’s new non-owner was announced, news broke that H&M would be forced to remove language such as ‘conscious’ from their products and donate €400,000 to sustainable causes to compensate for misleading consumers. Just days before, Kourtney Kardashian Barker – whose family has been labelled the ‘royal family of overconsumption’ – faced major backlash as she was named a sustainability ambassador for Boohoo, one of fast fashion’s most toxic villains. And whilst Patagonia can hardly be compared to fast fashion – which has created an all-too-affordable overconsumption problem, put millions of tons of textiles into landfill and been responsible for both ocean pollution and human exploitation on a massive scale – it should be noted that accusations of greenwashing would be better directed almost anywhere else in the industry.

Naturally, Patagonia’s political, personal and planet-friendly approach only makes it more popular, and the cycle continues: the more the company speaks out against consumerism, the more people become its consumers. But purchasing power is very real, and actions – or dollars – speak louder than words. Companies will go where the money is, and if consumer trends reflect demand for quality clothing with affordable repairs, recycling facilities and environmental awareness, supply will follow. In an ideal world, existing companies will pivot to embrace a different way of doing things that include treating textiles as a valuable resource; in reality, it’s likely we’ll see Patagonia-wannabes spring up. But if Patagonia has set the bar, anyone attempting to compete better be willing to surpass it, or an increasingly savvy set of shoppers will be all too quick to call them out.

Perhaps that is where Patagonia will succeed where others have not – it’s not just about effecting change within its own four walls, but impressing the importance of change upon those with their hands in their wallets, and creating a standard by which others can be judged. If anyone can push the envelope when it comes to transforming the culture, and strong-arm the industry into normalising his radical, unconventional, revolutionary ways, it may as well be Chouinard.