Artist Haig Papazian on leaving Lebanon and making a home in New York

Haig Papazian, multidisciplinary artist and violinist of Lebanese band Mashrou’ Leila, on estrangement, transformations, loss, and starting afresh in New York

Haig Papazian is someone who can’t help but create. The theme of expression has followed him throughout his life – from Bourj Hammoud and Beirut in Lebanon, where he grew up, to London, Paris, and most recently, Queens, New York. First came a love for the violin and drawing as a child, and an interest in architecture followed, which he pursued at the American University of Beirut in his late teens.

It was here, in 2008, that Haig met three like-minded friends – Hamed Sinno, Carl Gerges and Firas Abou Fakher – and formed Mashrou’ Leila, an indie rock band that went where others in the Middle East hadn’t dared. The band gained notoriety for its electric onstage dynamic, and bravely outspoken lyrics and commentary on issues including political freedom, race, gender, Arab identities, and supporting LGBTQIA+ communities in the region. They became arguably the most popular band in the Middle East and the most successful Arabic-language band in the world, and collaborated with artists including Yo-Yo Ma, Mika, Hercules and Love Affair, and Róisín Murphy, among others.

In a first-person piece for The New York Times, Haig explained that the band became a target for cynical politicians and pundits who stoked religious fervour. This backlash was exacerbated by an image of the late activist Sarah Hegazi holding an LGBTQ+ rainbow flag at their Cairo gig in 2017. Hegazi was arrested and later took her own life. This, coupled with the economic crisis in Lebanon and the pandemic, made it increasingly difficult to perform.

Haig now lives and works in New York. For ROADBOOK’s How Did I Get Here series, the multidisciplinary artist candidly reflects on touring, travel, coming to terms with loss, and what ‘home’ means to him.

What are you working on creatively at the moment?

These past two years, I’ve been working on a cross-disciplinary project called Space Time Tuning Machine. It’s a public, performative and personal musical narrative exploring the multifaceted meanings of home and exile. I started building musical instruments and synthesisers from scrap electronics and household materials I could find. Strangers and friends in New York lent me old keyboards, electronic toys, radios, speakers, and synths to build a musical machine that records and collects songs, memories, texts, poems, conversations, and voice memos, merging them all into one composition.

I have performed variations of the work, including at Joe’s Pub in New York, SXSW in Austin, and The Broad in Los Angeles. It’s still a work in progress. Every performance has presented many new challenges and possibilities that continue to shape the larger body of work. This past year, I’ve been working on many other projects too: music for a short film, the theme song for a podcast, illustrating a children’s book, and renovating a house.

You really are the definition of a multi-hyphenate.

That’s a great word! Although I’d use it to describe people like Angelina Jolie and Kim Kardashian. I’m more of a dilettante at the moment – dipping my toes into many different pools to figure out which ones I want to dive into.

I thrive when I’m working on multiple projects at a time, otherwise I get bored. Seeing the world through all these lenses and disciplines keeps me on my toes, keeps me curious, and opens doors to new and exciting collaborations. Opportunity is everywhere, all the time. Even at our darkest moments – especially at our darkest moments – you just have to see it.

Life in New York City

Are you enjoying living in New York?

I haven’t lived at one single address for longer than a year over the last decade. I’ve lived in between places most of my adult life. I guess I’ve always been nomadic by nature and necessity. The last three years in New York have been the longest I’ve been in one place without travelling. And even here, I’ve still moved from Brooklyn to the West Village, and now I’m over in Queens. My experiences of New York have been quite different in each neighbourhood, and every experience is an opportunity to learn something new.

What was it like being in New York during the pandemic?

The streets in New York were completely empty. For the first time, you could ride your bike around the city at any time of day and you wouldn’t see anyone. There was something very eerie yet special about that time. Many people living in my neighbourhood were out in the parks. All these different circles that wouldn’t usually intersect were in the same place, outside, together – six feet apart, of course – but together nonetheless.

With all the hardships the band was going through prior to the pandemic, and the worsening situation in Lebanon, this community at the park and all the friendships made things feel alright for the first time in a while. My relationships, and being part of a community – from Brooklyn to Beirut – are what kept me grounded. You can’t create art in a vacuum. If you keep your heart open, you’ll never run out of inspiration.

I moved to the West Village for a residency during the first winter of the pandemic. It was the loneliest I’ve ever felt, and I kept busy with various art projects. It was a way for me to come to terms with the traumas and grief of losing almost everything familiar; picking up the pieces of whatever was left, and starting over, on my own. Not having a support system during the pandemic was tough, and being unable to talk about the band and Lebanon with friends was difficult. I tried to keep my cool, but I was an emotional wreck on the inside, in survival mode. Yet there I was, applying for grants for art shows, moving homes, dealing with the repercussions of losing access to my entire life savings because of the Lebanese economic crisis, and dealing with the aftermath of my band being attacked. My physical health was deteriorating rapidly, I was constantly stressed and felt extremely vulnerable, I barely had enough money to eat, so I sold a lot of the things I owned to keep going. It all feels like a blur now; a series of unexpected events and worst case scenarios, one after the other, with no time to grieve.

"There are queer, immigrant artists from the Middle East who are forced to leave their homeland because of who they are"

How would you describe Beirut?

I’m not sure what Beirut is like anymore. Beirut was home, in a traditional sense. I remember it as warm and welcoming. Family is always close. It’s the sort of place where I’ll run into friends and have a spontaneous drink that turns into a three-hour conversation and dinner. A shared past is so powerful. It makes you feel grounded, and connected to your surroundings in an almost sacred way. It’s one of the things I’ve been struggling with in New York. But I have something different here, and I’m not sure how to describe it. I suppose I just feel like I can create a future here.

Haig’s ongoing renovation of a home in Queens

I was told you moved to a dilapidated building in Queens – how did this come about?

Fortunately, it’s no longer dilapidated! In February, my art residency ended at Westbeth, in West Village, so I had to move. Again, It was very difficult to find a place, and to move with a cat this time around, in the middle of a blizzard. I’m grateful to have found this place after a few weeks of homelessness and sleeping on friend’s couches. Part of the deal was to fix it up. It’s been a one-man show building the place, but I saw the potential of what it could be.

I’m not sure how long I will stay here, but I know that I’ll leave it better than I found it. That’s sort of how I try to approach life. It’s not always about total transformation; sometimes you just need to do something small. Perform a random act of kindness. That mentality is what inspired me to make this house more than just a home for me and my cat, Beau.

The idea is to renovate this home so that, when it’s ready, I can share the space with other people in my situation, so they don’t go through the troubles I dealt with alone. These are queer, immigrant artists from the Middle East who are forced to leave their homeland not because of what they say or do, but fundamentally because of who they are. It’s difficult losing everything you love and care about, and not having the option to take time off to grieve. I’ve been fortunate enough to find work, a home, and a livelihood here. I will forever remain grateful to the beautiful friends who have been supportive, who taught me asking for help isn’t a weakness. It’s still not easy for many of us, and there are so many uncertainties, but these past years I have learned a lot. And I’m hoping I can use this as an opportunity to make it easier for others to do the same. Whatever I make out of this place, I’ll take that experience with me wherever I go.

Touring with Mashrou’ Leila

Before New York, you were touring a lot with your band Mashrou’ Leila – what was that like?

Imagine a band with a touring schedule on a Lebanese passport. Every country you go to, you have to apply for a visa and they take away your passport for a couple of weeks. I don’t know how we made it like that for ten years. We got lucky and we had patience. We travelled everywhere from major cities to obscure towns and villages across the Middle East, Europe, and North America.

I’m a Saggitarius, and my friends tell me that I always need a change of scenery. The fact that we were touring, and that it became our life, was perfect. It opened up a whole other universe for me. Growing up, I never thought I would be able to leave my Armenian neighbourhood. Life throws exciting things at you and this always leads to learning, discovering, seeing more art, and tasting more food. Travel changes the way you look at everything. Touring was an eye-opening experience.

What did you learn from these encounters?

I met so many inspiring people, whose courage taught me to be more at ease with my own queerness and identity. Meeting these amazing people showed me that even though we were born in different parts of the world, there are things that we share, no matter how different we look, act, or think. These connections turn strangers into friends, even ones that you might never see again in person.

Travel changes the way you look at everything. Touring was an eye-opening experience

How does your background in architecture impact how you experience different destinations?

Studying architecture allowed me to change perspective, be critical and engaged, socially and politically. It changes the way you see the world – you start to spatialise every movement and aspect of your life. I did an internship in architecture in Paris right before the band started and I remember walking through the city and coming across the buildings I’d seen in pictures while studying. For someone who had never left Lebanon before that, having access to public spaces, galleries and museums was amazing.

I never imagined architecture would be a career. I think my parents agreed to me doing it because they thought it was like engineering or that there was some kind of science behind it. They didn’t know about the crazy, designy, conceptual part of constructing a building.

The early days of Mashrou’ Leila

And it was here you met the band. What were the early days like?

When we started the band, the idea was to approach music the same way we approached design – as something collaborative, and constantly evolving and reshaping. We sounded horrible at our first show: we weren’t trained musicians, but we had big dreams and there was momentum. It felt like it was all meant to be.

Do you believe that things are meant to be?

Luck is something that you bring to yourself – you put yourself out there. We got lucky, but we worked our arses off to record the album. We pushed ourselves to do a lot of things, and when you put that out into the world, a lot of positive things come back to you. I think that the more you explore, the more you see the possibilities. You create your own kind of luck; you can’t leave things to chance.

That said, conflict is an essential component of creativity. Not just because conflict creates necessity, and necessity drives invention, but because anger and indignation are incredible motivators of artistic expression. My anger, for example, about what’s happening in Lebanon, has been the catalyst for an intense period of growth, as an artist and a person.

When something unexpected turns your world upside down, it takes time process what really happened

Do you long for Beirut?

Yes and no. My family is there and I haven’t seen them for four years now. A virtual connection isn’t the same as being in the same room. I feel like when I go back, I might not recognise the city anymore.

Even though I always wanted to leave Beirut – it always felt too small, claustrophobic even – it was always a place I would go back to because it was home. But this idea of home being a fixed place isn’t real. The definition of what a home is and where you belong isn’t tied to one place; it’s something that you take with you, that moves with us, around us, and we shape it as it shapes us.

How do you reflect on the events that happened after the Cairo gig?

When something unexpected turns your world upside down, it takes a while to process what’s really happened. I knew that things were going to be different from then onwards. I remember the sleepless nights. Everything was up in the air and uncertain.

Do you feel like you’ve changed as a person, during this journey?

I feel like all parts of me coexist together. I have every version of me somewhere inside myself. The successes, the failures, they’re all here.

I don’t want things to go back to what they were, and they never will. We experience time in one direction – forward – and that’s one of the few constants in life. We can’t go backwards, even if we want to. Whether good or bad, a person is a collection of experiences, people, places and everything they’ve lived through until this point. I know I’m a different person now than I was last year, but the person I was ten years ago is still part of me. I’m the same kid who wants to do ten things at one time, I’m just a little older. And a little wiser.

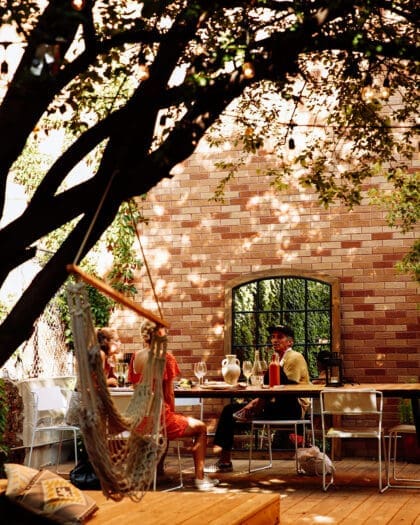

Photography by Timothy O’Connell