How London’s Caribbean community has shaped the city, from supper clubs to festival food

Whether it’s the ‘shebeen’ parties that brought together food and music or the festivities of Notting Hill Carnival, modern London has a lot to thank its Caribbean community for

Though Black communities have existed in the British Isles for centuries, it was arguably during the two world wars – when migrant communities from the British colonies in Jamaica, St. Lucia, Guyana, and parts of Africa started to settle in the UK in higher numbers – that a new generation of distinctively Black-British people emerged.

The mid-20th century saw many of these newcomers become disillusioned with the hard times and harsh climates of Britain. This was highlighted in numerous pieces of fiction and non-fiction, like Samuel Selven’s novel The Lonely Londoners and poem ‘It Dread inna England’ by the iconic Linton Kwesi Johnson.

Those congregating in core cities like Birmingham, Manchester and London established communities and began building new lives for themselves. As is often the case with sizeable migrant groups, with these new beginnings came a longing for old familiarities, such as the sound of their own music, and the taste of their own food. For survival as much as nostalgia, people held on to what they could from their old lives, which was largely culture, language and food.

For survival as much as nostalgia, people held on to what they could from their old lives

The majority of the London neighbourhoods that Caribbean migrants ended up settling in were undesirable inner-city areas, as they were often subject to bigoted landlords and lenders, who made it hard for them to put down roots in many parts of the capital. Areas like Brixton in South London, Notting Hill in West London, Hackney in East London and Tottenham in North London became hubs for these communities, as new migrants pooled resources and lived together after first arriving.

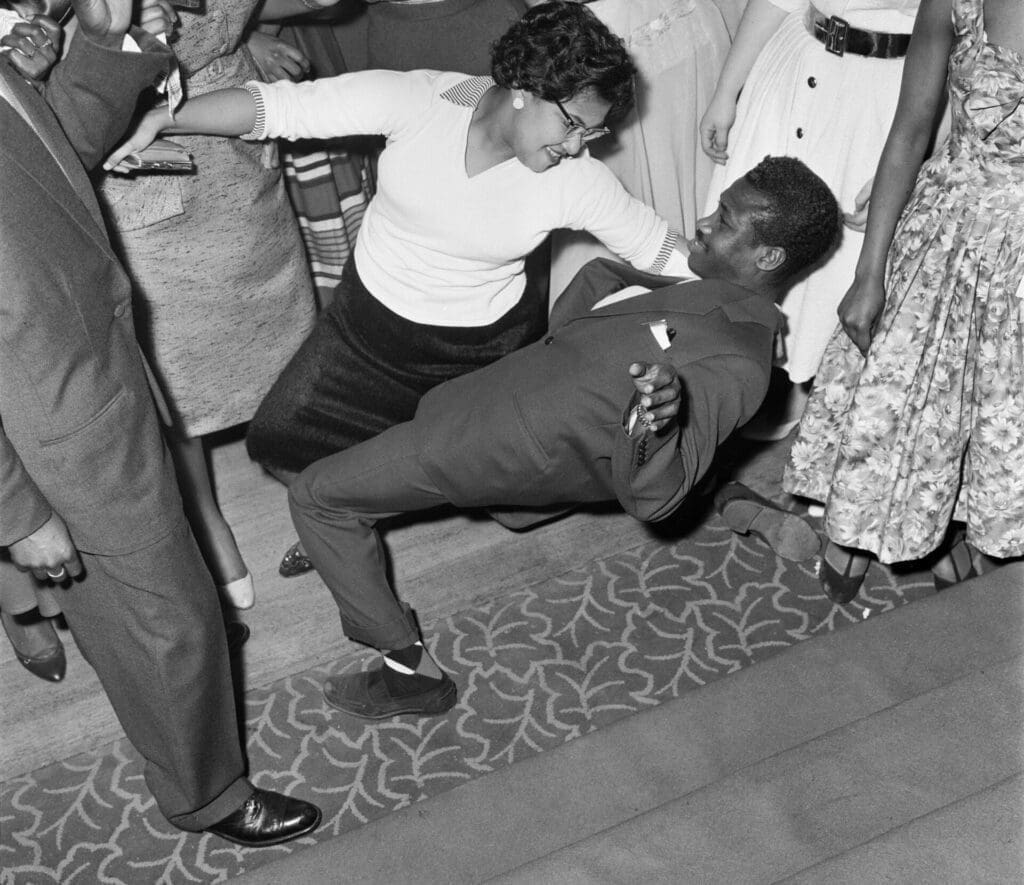

In the cultures of the many Caribbean islands – which descend from a kaleidoscope of African, Indian, Spanish, and Chinese heritages – food and music go hand in hand. As new Caribbean migrants were implicitly and sometimes explicitly ostracised from patronising public hospitality spaces, they formed their own. Events known as “shebeens” were joyous and raucous occasions. They involved dancing to ska and rhythm and blues; drinking rum and stout; and eating until the late hours of the morning, and took place in the basements of Caribbean homes, open to people of all walks of life.

These unofficial spaces slowly became official, and records suggest Caribbean bars and cafes have existed in the UK since the late 1920s. These include the Caribbean Café at 185a Bute Road in Tiger Bay, Cardiff, and the Florence Mills Social Parlour at 50 Carnaby Street in Central London, which was founded by Sam Manning and Amy Ashwood – a political activist, and first wife of Jamaican political activist Marcus Garvey.

By the 1960s, the rapidly growing Caribbean population of the UK numbered in the hundreds of thousands, and the basement jams and tightly packed restaurants couldn’t contain the full gamut of the culture. And so, in the mid 1960s, the now world-famous Notting Hill Carnival was born. Here, the vivid colours, bright costumes, and steel pans of Caribbean processions that had been celebrated for centuries in British-held locales of Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, Dominica and more made their way to Britain and the streets of West London.

This incredible affair put Caribbean food and music on full display for all to see. It coincided with a boom in popularity for reggae music, led by Bob Marley and a wide cohort of artists before him, which boosted the overall awareness of Caribbean culture both in the UK and across the world.

This cultural explosion was occurring against a backdrop of social tension. Those of Caribbean descent still faced severe residential and occupational racism, which stunted opportunities for life progression. This discrimination was compounded by violent treatment from the police and far-right groups, which led to numerous riots in Caribbean neighbourhoods as the communities fought back.

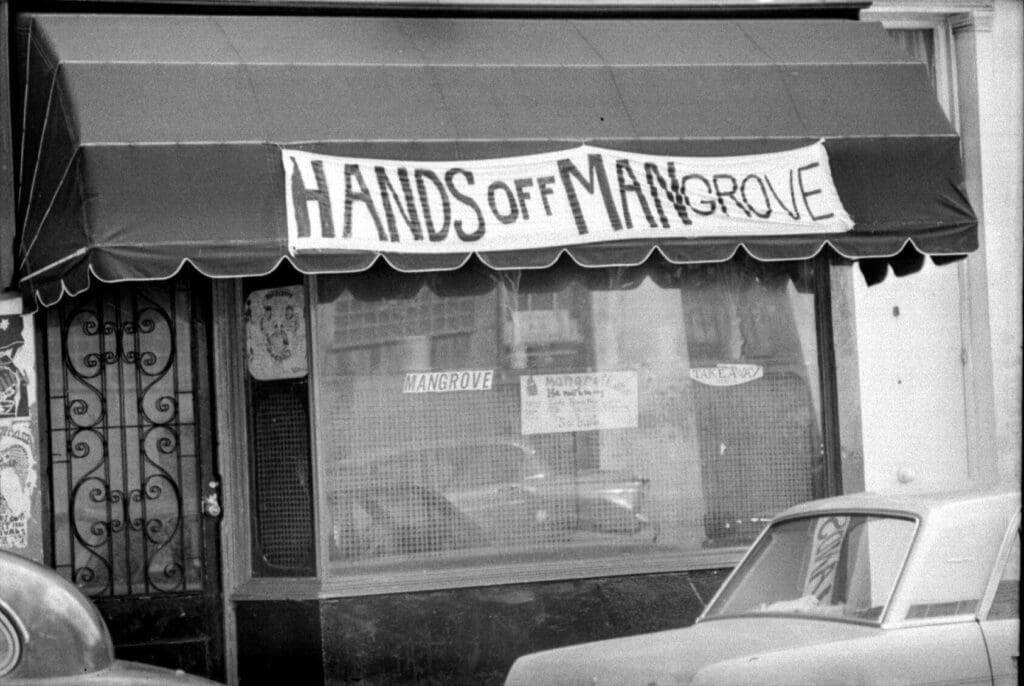

The public spaces that were afforded to Caribbeans and Black Brits – like the growing number of restaurants – proved vital in aiding these activist efforts, none more well-archived than Trinidadian-born Frank Crichlow’s Mangrove restaurant, which was in the same West London locale as the carnival. These places (often termed “frontlines”) were crucial not only in securing hard-to-come-by home cooking, but as places to meet and bring about social change.

Up until the 1980s, Caribbean food places were still somewhat of a rarity. The majority of establishments up until this point were bakeries like Mr. Patty in Harlesden, North West London, which only sold baked goods and therefore required a simpler array of produce and resources than a fully fledged Caribbean restaurant. The hospitality business, like many others, requires great amounts of financial backing to get off the ground. When travelling around the UK, I met the founders and owners of many Caribbean shops, and was told by them that this backing from banks and other private investors was incredibly hard to come by. If you did manage to secure funding, prejudiced landlords formed another barrier to success.

Caribbean food remained an afterthought in the wider food scene of Britain. It was common for Caribbean entrepreneurs to sell their wares out the back of cars and vans, like Bernard Miller of the popular Roti Stop in Stoke Newington. Vendors were also known to set up outside Black-owned or allied pubs and clubs like The Palace Pavilion – still standing but disused in Clapton, East London.

As the Caribbean community grew out of the crippling poverty of earlier generations over the course of the the 1990s, Caribbean takeouts and restaurants boomed across London and other major British cities. The key difference in these British-Caribbean shops versus their counterparts back home was the diversity of food on offer. While the roadside shacks and shops found in places like Jamaica often peddle a dozen or so local favourites, the diversity of the UK Caribbean community meant shops often catered for all these people, selling the likes of roti, jerk chicken, rice and peas, and other classics.

Today, the ability to leverage new forms of media for community support allows Caribbean restaurants of all shapes and sizes to exist in the capital, from street food classics like Rudie’s Jerk Shacks to high-end restaurants like East London’s Ayanna’s, reimagining the same dishes in a fine-dining setting. The same can be said for the dishes of Trinidad and Tobago, also served across the spectrum from takeout shops like Roti Joupa’s and Roti Stop in Hackney, to restaurants like Brixton’s Fish, Wings & Tings.

A majority of these spots were established by older generations, and with each passing year we increasingly see the younger generation fusing their London upbringing with their island heritage. Veganism, which has deep roots in Caribbean Rasta culture, is increasingly gaining traction across Europe. Eat of Eden, which continues to grow at great speed across London, represents this vividly. After-hours bars like South London’s Three Little Birds (now mainly a catering company) and Buster Mantis (where the legendary Steam Down jam is held) eschew the obvious homages to home of Bob Marley murals and palm trees, and instead favour an effortless blend of different roots, in much the same way as the founders blend their own identities.

The community continues to grow out of the legacies of pioneers like Ainsley Harriet, Rustie Lee and Levi Roots. The irony now is that the once-rundown areas of London like Hackney and Brixton – which were the only accessible places to live and do business – are now quickly becoming out of reach due to gentrification, a complex topic that could easily fill its own tome. This rapid shift has caused many of the legendary late-night Caribbean dives like Hackney’s Visions Bar and People’s Social Club in Islington to shut for good, leaving a dearth of options for those of an older age group and pushing them further out to the fringes of London to places like All Nations Bar in Tottenham.

The main reason for my passion in documenting this scene is to protect the legacy of this community from the erasure that can come with gentrification. We can see how Caribbean food has paved the way for several different strands in modern hospitality across the UK: the basement dives that are akin to supper clubs of today; the ‘takeovers’ – weekend appearances in clubs that resemble contemporary pop-ups; and the street food of Carnival, which preceded the heavily commercialised street food and festival catering industries of today. London and UK culture as a whole owes a great deal to the food, music and energy that was brought over by its Caribbean communities.