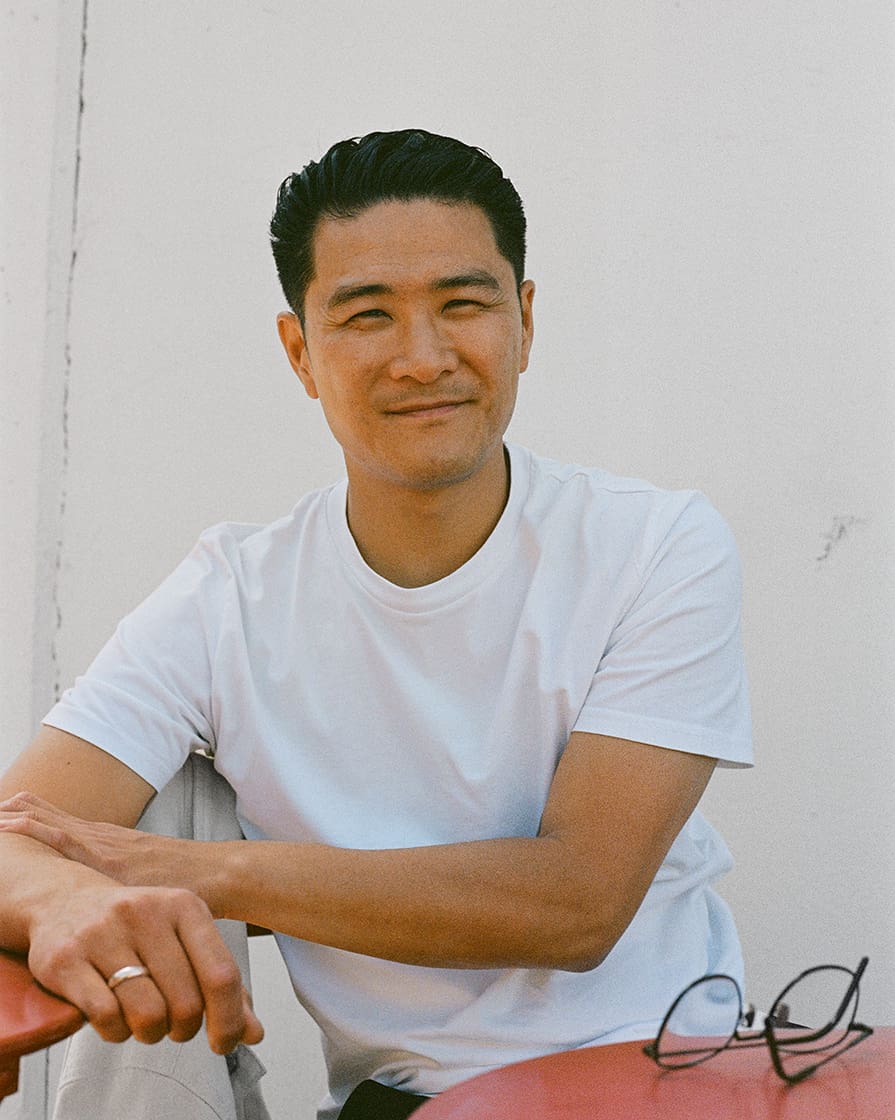

Copenhagen chef Kristian Baumann on the search for identity

Born in Seoul but raised in Denmark, the lauded Copenhagen chef behind two-starred restaurant Koan shares his compelling journey.

In a city revered for its era-defining restaurant scene, it’s not always easy for a chef to make a splash. Yet on Copenhagen’s northern shores, a short hop from the shipping terminals that have welcomed new arrivals for centuries, Kristian Baumann is doing just that. It’s here that the Korean-Danish chef chose to locate Koan, which – just weeks after opening in 2023 – picked up not one but two Michelin stars to gain recognition as one of the best restaurants in Copenhagen.

Inside this sophisticated 23-cover space, with its blonde wood, open kitchen and harbour views, smartly clad staff ferry spectacularly pretty plates and tipples of Korean sool to guests. Baumann’s inventive cooking melds elements of Korean and New Nordic cuisine, championing local seafood, micro-seasonal vegetables and foraged ingredients across tasting menus where caviar-topped tofu, gamasot-cooked rice and seaweed ice cream vie for attention with immaculately presented dumplings, broths and kimchi.

Yet as serene a setting as Koan – a Zen Buddhist term for a riddle without a solution – might appear, Baumann’s own journey has been anything but, representing the culmination of a highly personal search for identity. Born in Seoul before being adopted, along with his sister, by Danish parents, he’s lived most of his life around the Danish capital, where cooking duties at boarding school kickstarted his culinary career.

Gaining experience in France before returning to some of Copenhagen’s most prestigious kitchens – including Relae and Noma – Baumann later set up his acclaimed first venue, 108. When the pandemic closed that down, Koan found form as a popup, operating as a takeaway until scouting venues across the city resulted in Baumann settling on the restaurant’s current waterfront location.

From the Rokkedyssegård strawberry farm where he used to work, Baumann speaks to ROADBOOK about the journey that has shaped him, the blending of cultures that informs his cooking and what he’s learned about himself along the way.

How has your upbringing shaped who you are today?

I had a very regular Danish upbringing in a small city outside Copenhagen, yet figured out very fast that I didn’t look the same as the other kids on the football team. My parents were very good at talking to us about our heritage, though, and we went to a lot of Danish-Korean gatherings. We always had chickens and our garden was full of beautiful berry trees – I loved being outside. Home was a beautiful escape when I started my career; I would cook for my family and let my creativity flow.

What prompted you to launch your own venue?

I’d worked in many kitchens in France and Copenhagen and it was while working at [Norrebro restaurant] Relae, that I decided to hand in my notice. At the time I didn’t have anything prepared – neither investors or a location. It was just an idea on a small napkin, but sometimes I feel the best journeys start that way.

I asked Rene [Redzepi] and his team at Noma for their advice and they came back and said they wanted to build a restaurant together. The result, 108, was a Nordic restaurant that had great success before closing during the pandemic, which led me to pursue the idea of Koan. Koan is a place where Denmark meets Korea and distils the memories of all the trips I’ve had to Korea, mixed with my personality and local ingredients to create an experience that’s unique to Copenhagen.

How did you reconnect with your Korean heritage?

I was always curious about my birth country and always looking for my place in life. I noticed that if I was cooking with, say, cucumbers at work, I would always approach it in a completely different way to those around me. Being able to pinpoint that I was thinking differently about the same ingredient was something I found very interesting. It was this that gave me the push to investigate my heritage.

When I first went to Korea I leaned into every experience and tried to figure out why, for example, the jangs [Korean sauces] are different to those in Japan, or why Buddhist nuns and monks eat without alliums in the temples. I kept my antennas on and luckily met a lot of gracious people to share knowledge with me. Every time I visit, I learn something new; I don’t feel lost like I used to – that’s what Korean cuisine has done for me and my life.

Were there any revelations along the way?

Visiting [Buddhist nun and renowned Korean temple chef] Jeong Kwan in Korea was an incredible experience. While foraging, she stopped to point out a 500-year-old tangerine tree, and I realised how insignificant we are. At the temple, they slice and sun-dry satsumas, and it was one of the best things that I’ve ever tasted. That moment is represented on our menus with flecks of dried citrus in one of our rice dishes.

We also tasted her soy sauces, some of which have been aged for decades. I remember asking her about how she made a particular vinegar and expecting her to come back with specific percentages, but she just calmly replied ‘Sun, earth and wind’. Every time I visit the temple it leaves me in more peace with myself.

How do the two food cultures compare?

In Korea, there’s generations and generations of knowledge that we just don’t have in Denmark. Over there you have so many businesses producing and selling seaweed based on preservation knowledge that’s been passed down over many years. We have great seaweed in Denmark too but it’s usually only available fresh, as seaweed farmers here don’t have the knowledge of ageing it. Evolution is important but it’s crucial that knowledge lives on for the next generation.

"I don’t feel lost like I used to – that’s what Korean cuisine has done for me and my life"

Were there any culture clashes?

Fermented skate wing is a very traditional Korean dish. Skates urinate through their wings and are fermented in their own urine. The time I tried it, it was virtually raw and smelled like ammonia. While I understand the dish’s tradition and its heritage, it’s a dish that will never be my thing. At the same time, we have things in Europe that many people from Asia would think are weird – why would anyone eat a mouldy piece of something called cheese?

What are the star ingredients or techniques you enjoy working with?

We try to highlight Korean seasonings in particular. This includes Korean red chillies, which can come in many forms such as gochugaru. We try to alter it so it has a beautiful spice and sweetness at the same time. We are always trying to capture an ingredient’s essence and push it to a level where it’s showcased best.

Because seaweed is such a big part of Korean culture we try to showcase that aspect. Gamtae is a very fragile seaweed harvested by hand that’s washed in a bath of water and sorted into sheets that are then pressed and toasted. The amount of work that goes into this is incredible and results in a versatile seaweed with slight truffle notes. If you overcook it it becomes very bitter, but you can create beautiful umami sensations when used sensitively.

Are there any dishes you’re particularly proud of?

Our white kimchi is very close to my heart and the plates we serve it on have a very special meaning. They were made by a Korean artist who has travelled to China for many years to collect fragments of porcelain that date back to the Ming dynasty. Looking into the bowl, you see this beautiful old and new life together – something I felt was perfect for the white kimchi flower.

Another, the Kkwabaegi [a traditional twisted donut], is a tribute to the afternoon snacks my wife and I would have on our trips to Korea and this dish transports me back to those street-food stalls.

How important was the award of two Michelin stars?

I’m so happy to be based in Copenhagen as the quality is so high. But Michelin is notoriously tough on restaurants here – this year there was just one new star awarded in Denmark despite there being so many worthy venues. The first day we opened, the second guest of the night was a Michelin inspector; we received the awards invitation within ten weeks.

I never thought anything would happen at the ceremony and I said to the team that we should be happy just to be there. When they announced the one-star restaurants, we weren’t on the list. But suddenly we were awarded two stars and I felt this great weight that I’d been carrying around for years just disappear. My wife and I risked everything to be here – the Michelin recognition secured more sleep at night and meant we could hire more people to make the experience even more special for our guests.

What has opening Koan taught you about yourself?

Only a crazy person would start a fine-dining restaurant in the middle of a global pandemic. But after all the early struggles, we’re coming out the other side, and I’m so happy we went through that period as it makes the team and I so much more resilient.

I don’t feel lost like I used to do and that’s what Korean food culture has done to me and my life. We’ve had diners from all over the world, but I’m flattered that we get so many Korean guests, many of whom tell me there are so many flavours they recognise, but also lots they don’t. The Danish guests say the same thing. I finally feel accepted and OK with being ‘in-between’. Identity is something that I’ve struggled with for many years and my message for anyone with similar struggles is that you should embrace who you are – beautiful things can come from following your own journey.