The story of Bangkok’s Indian community, from samosas to somtam

From a shared love of superstition and folklore to a penchant for eye-watering spice, Bangkok’s Thai-Indian community is distinct, characterful and deeply rooted in the city

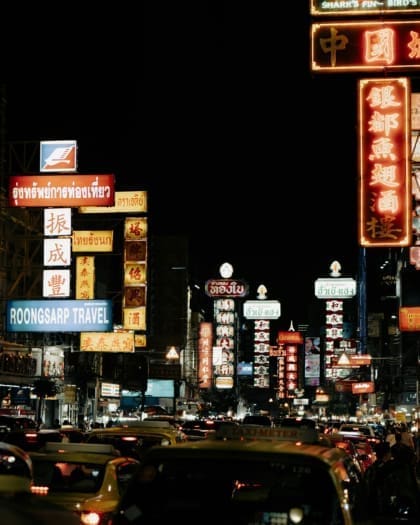

On a street corner in Bangkok’s Ratchaprasong district, in the shadow cast by the hulking concrete of the BTS Skytrain Chit Lom station, sits a glittering shrine surrounded by flowers as golden as the statue perched at its centre.

This shimmering structure, usually thronged by people, is the Erawan shrine, built under the advice of an astrologer to rid the area of bad karma and negative influences. The serene golden effigy is the Phra Phrom statue, the Thai representation of the Hindu deity in charge of creation, Lord Brahma.

Since the very beginning, Thailand has been influenced by India, especially in the spiritual realm. In fact, much of Thai beliefs stem from India. Both share an inherent love for mythology, rituals, lunar calendars, and astrologists. Waves of Indian beliefs trickled into the Thai kingdom, blending themselves with the country’s rich folklore.

While Indian influences have long been present in Thailand, Indians themselves started to appear in Thailand much later. Escaping their drought-stricken villages of North India in the 1920s, they arrived on cargo ships, docking at rural provinces.

Hustlers from the get-go, they reinvented themselves as merchants, trading with whoever would do business with them – namely the other set of newcomers to Thailand: the Chinese. Soon, the nascent Indian community picked up a survivalist command of the Thai language and saved enough money to make the journey into the bustling capital of Bangkok, where they settled in the Pahurat district, part of Bangkok’s Old Town and affectionately known as the city’s unofficial ‘Little India’.

As a fourth-generation Indian, I’m regularly lured to Pahurat by the tantalising aroma of freshly fried samosas. My visits usually start at the golden-domed Sikh gurdwara, where I help out at the free kitchen and commune, and pick up the latest gossip before heading over to Royal India restaurant – a longstanding local icon – for some Indian sweets and a steaming cup of cardamom tea. When Bangkok’s infamous humidity becomes unbearable, I usually seek refuge in nearby local department store The India Emporium and use the opportunity to update my set of bangles, bindis, yoga pants, and Indian groceries.

Stories of the city’s Indian diaspora pepper Bangkok’s Old Town, a mesmerising and ever-changing neighbourhood with dozens of cafes converted from old shophouses, and street art lining the walls. The newly renovated canal streets of Khlong Ong Ang feature vibrant murals of the Chinese, Vietnamese, and Indian experience, highlighting the communities’ contributions to the area’s development.

There’s one mural in particular that always draws my attention: a turbaned man casually leaning against rolls of colourful fabrics. He’s relaxed, as if he’s taking a break; almost like he’s conversing with the fruit vendor parked in front of his shop. The man reminds me of my Sikh grandfather, though his body language is completely different, because I’d never seen my Papa-jee relaxed, ever.

Slightly hunched, with a permanent furrow between his brows, he always looked like he was prowling for opportunities, ready to pounce when the timing was right – a trait my father and much of his generation inherited from the first Indians who stepped onto Thai soil.

The five flavours of Thai cuisine – sweet, sour, salty, spicy and umami – balance out the richness of Indian masala-laden curries

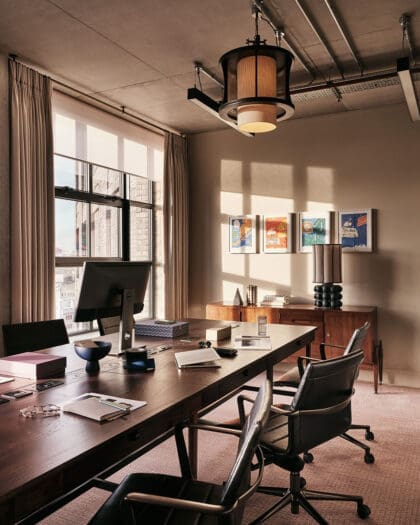

When they heard of the rising number of expats in the 1960s and a property boom in any up-and-coming neighbourhoods, a large number of opportunistic Indians swooped in, parking their ample savings into real estate as shophouses, apartments, and hotels, mainly on the Sukhumvit strip. The area is lined with hotels, apartments, tailors, and supermarkets that are owned by several generations’ worth of Thai-Indians.

It’s no surprise to see many Indians going about their business in Sukhumvit’s swanky streets, where you’ll find several Thai-Indian tailors. Of course, there’s much debate about the best one, but I would recommend Rajawongse Clothier by Jesse and Victor, a hole-in-the-wall establishment that’s the first choice of diplomats, businessmen, and recently made crypto-millionaires alike.

The languages you’ll hear on these streets also speaks of a clearly defined Thai-Indian identity, with a curious mix of Thai, Hindi, Punjabi and English.

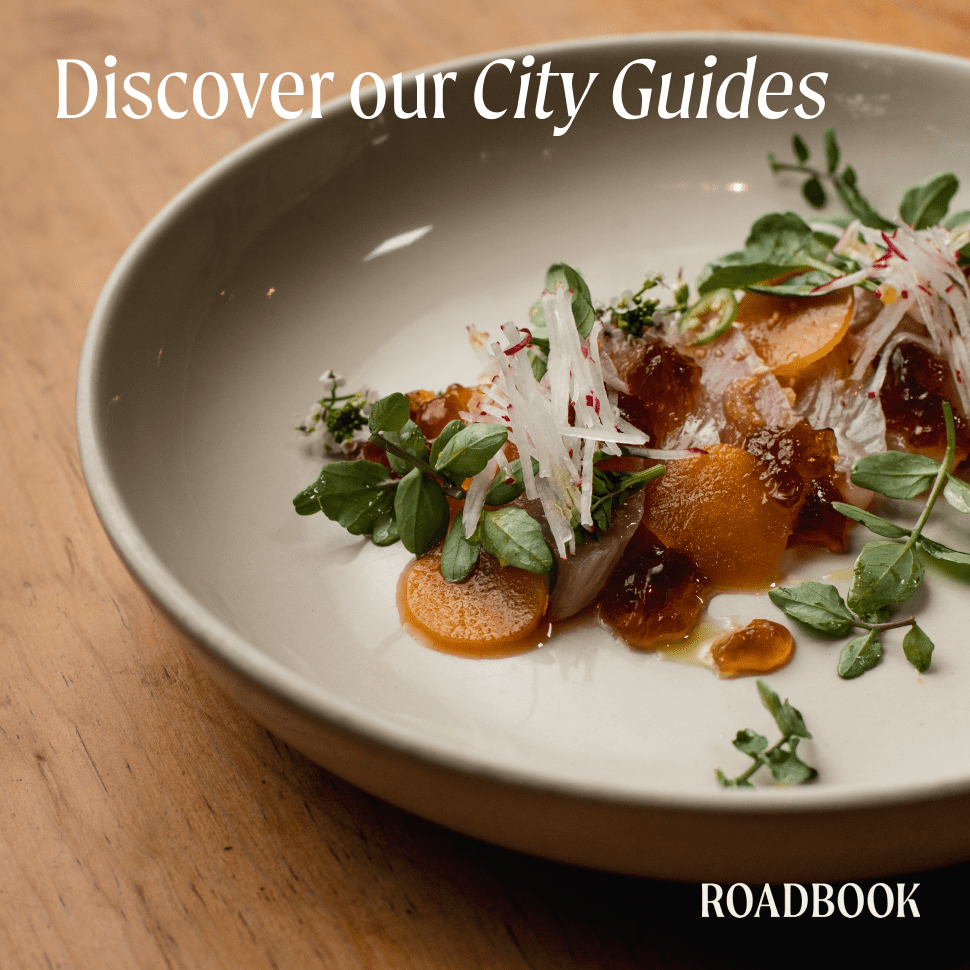

Cuisine, too, tells these stories: the trademark five flavours of Thai cuisine – sweet, sour, salty, spicy and umami – do well when it comes to balancing out the richness of Indian masala-laden curries. The more authentic the dish, the better, and the same attitude goes for the spice levels: no matter the influences, heat is a way of life.

You’ll find plenty of diversity among the different ethnicities found in Bangkok’s Indian diaspora too. For every North Indian flatbread, there’s an equally delicious South Indian dosa, even when you’re right in the centre of Bangkok.

Best accessed by skytrain, the Silom neighbourhood is where you’ll find the Tamil-style Sri Maha Mariamam temple and an array of tempting places to eat that look to the flavours of South India. Sugam is one of the best restaurants to find a proper dosa, while Sunanada offers home-cooked vegan meals.

Probably those most fascinated by the Indian diaspora in Thailand are the Indians themselves – even my Indian expat friends grow wide-eyed when I speak Thai or croon out the latest Bollywood tunes.

When they’re missing their home countries, I usually take them to contemporary offerings like Punjab Grill. This fine-dining establishment is on par with the glitzy urban five-star restaurants of Delhi and Bombay, with live singers and Indian waiters. And to end the night, we’ll usually hop over to Charcoal for creative cocktails, desserts and paan, a betel leaf after-dinner treat.

Like all diasporas, food is the pillar of Thai-Indian identity. For my family, the hunt for authentic flavours reminiscent of home coupled with fascination for new dishes in their adopted country made for some interesting dinners.

My grandmothers’ recipes and mothers’ discoveries always found their way to the dinner table, where so much of our conversations were about reminiscing about the past and navigating the present.

I remember asking my grandfather why he chose to settle in Thailand versus his contemporaries who went to Singapore and Malaysia.

“Is it because they were colonised? Is it because he wanted to get away from the British colonisers?”, I would ask. He would nod his head ‘no,’ and then explain that the decision boiled down to two words: tom yum. Thai food – it was the deciding factor for choosing to make Thailand his home.

Read more: the best restaurants in Bangkok, according to a local editor