Four Lagos-based artists and designers on reinterpreting traditional craft

Lagos-based photographer and writer Wami Aluko explores how contemporary artists and designers are collaborating with local craftspeople to push the city’s design scene forward

Moving through the streets of Lagos, you may stumble across cobblers, roadside tailors, basket weavers, and metal welders transforming materials around them into new, beautiful and functional forms. These artisans make the most of limited resources, manipulating local materials using skills accumulated through years of practice.

In Lagos, craft is present across a whole spectrum, from roadside makers to cutting-edge furniture designers and studio ceramicists. We speak to four Lagos-based artists and designers who have forged their own practices, developing traditional notions on craft and creating functional, contemporary and consumer-focused art pieces with global appeal.

Olubunmi Atere, ceramist

Olubunmi Atere is a contemporary ceramicist who hand builds and carves enchanting pieces with clay. Her sculptures are intended as art objects, although some may function as vases, and all are packed with meaning and story. She carves intricate motifs into her pieces, including the adinkra symbols of the Akan people in Ghana, as well as those of her own creation. Nature plays a prominent role in her work, apparent in the earthy tones and organic forms that take their cue from branches, sprouts and flowers.

Can you tell me about your relationship with clay and your creative process?

There is something about the primitive way of doing things that appeals to me. I build my work by hand: it’s just me, my clay and my knife. I really feel at home with clay. I stick to hand building so that I’m fully present and immersed in the process. I gain a deeper understanding of it that way. The good thing about clay is the liberty that you have – you can make mistakes, it creates room for you, it’s so soft. If it gets hard you can break it down and make the same form again, or something new. This versatility and malleability has taught me to apply these qualities to other aspects of my life. Clay allows you to create something unique every time you work with it.

Nigeria has a rich tradition of artisanal craft. Does this tradition inform your work?

I travelled a lot across states in Nigeria growing up and was very in touch with the traditional crafts scene. I grew up mainly in Ondo State, and my dad ensured I was immersed in the rituals, festivals, and family celebrations across the state. I would help my grandma process kola nuts after harvesting, and take them to the market with her. When she was setting up her stall, I watched other people around her working with clay, making pots for cooking or for collecting rainwater.

I once visited Dada Pottery in Ilorin, the capital of Kwara State. There are so many potters there, and they are mostly women, building with their hands with traditional methods. They use a small bowl as a mould, and press clay into it, and build on it, turning it in their hands. It’s really meaningful.

These traditional artisans are all artists in their own way, with a different focus. They build standardised pieces using skills passed down to them, in order to sell their creations to the people that need them. I consider myself a contemporary ceramicist. Though I incorporate some traditional hand-building methods, I want people to feel my work – to learn, interact, and spark a conversation – to engage with it in a different way to a utilitarian pot.

Josh Egesi, industrial designer

Josh Egesi is a design artist and the founder of Ike of Lagos, an industrial design company where he manufactures bold, minimal, and futuristic furniture pieces with a strong Nigerian narrative. The word ‘Ike’ is an Igbo Nsibidi symbol for strength. He was drawn to that particular symbol whilst designing a space in Onitsha, Anambra State.

It was through this work as a spatial designer that he created his first product, the Ikenna vintage fan, which then led to other products such as the Ikeoku floor lamp, and the wood and glass Ayo bench. Afrofuturism is an important influence in his creative process: he works at the intersection between art, design, science and engineering, and often reapplies shapes and structures into new pieces, such as the wooden tripod legs that support both the fan and the floor lamp designs.

What role does art and traditional craft have in the industrial design scene in Lagos?

There is craft, there is art, and there is industrial design. Craft is like a documentation of history: a community has a particular style they practise, which is passed down from one generation to another. Craft objects are not to be mass produced because artisans don’t have the capacity for that. Meanwhile, art is very niche, and every artist has their own style. Industrial design on the other hand is for a mass market, to be mass produced. Industrial design borrows from craft and art and creates products for the general market. For instance, my Ayo bench design takes its starting point from the traditional Ayo game, one of the oldest games in Nigeria, which is craft. Then there is the story of the creation of the Ayo bench, which is art, and finally the piece itself, which is design.

What are some of the limitations you have faced as an industrial designer in Lagos?

Design has never been widely recognised or practised in Nigeria. For instance, a company called Eleganza, which made coolers, biros, and other household items when I was growing up, had its design team based in China. We never had an industrial designer who was designing for Nigerians in Nigeria. Now, we have up and coming African designers creating locally, and shows like Lagos Design Week supporting this growing industry.

I work with one or two artisans to manufacture my products, but it’s not always easy. Again, industrial design is different from craft. With design, you create a new process with every new product. A professional artisan can struggle because they don’t understand your vision, so it can be stressful. You have to pay to train them, so they can learn your process, so it is capital intensive. That is one of the reasons why I put a lot of time into doing these things myself and building my products with my own hands.

What inspires your design practice?

I am greatly influenced by experiences, nostalgia, and things I see and feel around me. These are often highly spiritual, especially as you don’t have control over how your day is going to turn out. For instance, I originally created a wooden iteration of the Ayo Bench. I began to notice how I kept putting wooden things into glass containers in my day-to-day life, and realised how good wood looked inside glass. I thought, what if I redesign the Ayo bench to have wood embedded inside glass? It made me think of a line I heard by Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie on the restitution of African artefacts, and how our works are kept in cold and clinical glass barriers.

That is the story I decided I was trying to convey through my products. I am in a constant conversation with my environment, present, and past, and if it doesn’t intuitively hit me as something that needs to be made, I won’t do it. My ever-changing environment is what has shaped me, especially Lagos and all of the other places I have been.

Yadichinma Ukoha-Kalu, multidisciplinary artist

Yadichinma Ukoha-Kalu is a multidisciplinary artist who works intimately with modern materials such as plexiglass, pastel, and soapstone – which she discovered while attending the Harmattan Workshop In Agbarha-Otor, Delta State. Her work plays with the boundaries of geometric shapes, transforming them into inventive forms. Marrying her intuitive art practice with her graphic design background, she recently created a contemporary iteration of a classic Ludo game board – a multiplayer game that derives from the Indian game Pachisi, renamed ‘Ludo’ by the British, and one of Nigeria’s most popular board games. The board was produced in partnership with Opemipo Aikomo of Wuruwuru collective.

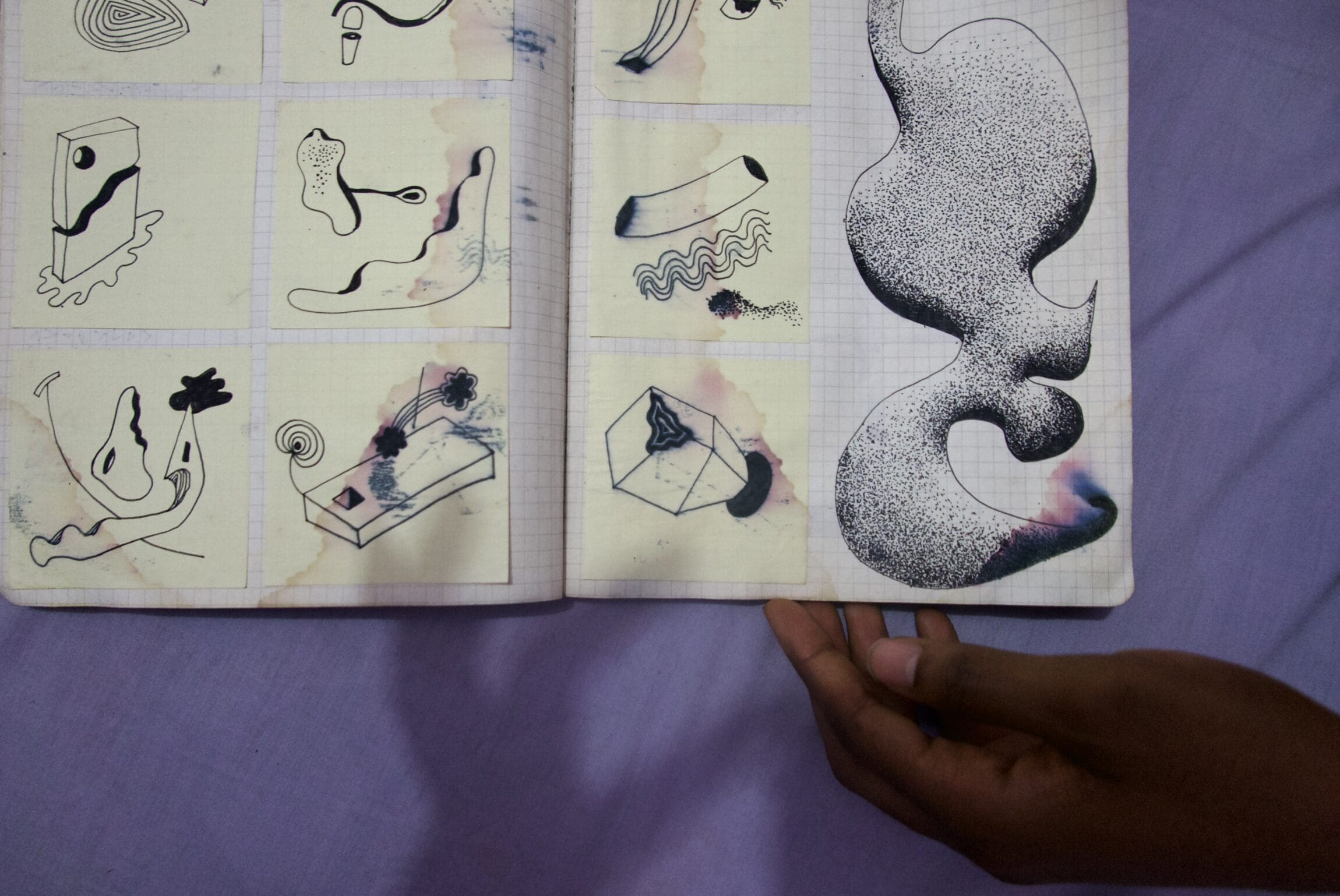

How do your sculptures typically begin?

The sculptures are three dimensional manifestations of the shapes in my abstract paintings and drawings. Instead of silently drawing on paper, you have this object that you can rotate, see and observe.

I am often drawn to surrealism because it involves taking elements out of your reality and transforming them. My soapstone sculptures are a good example of this. I imagine them as playgrounds for my fingers – something you can pick up and hold and have a sensory experience with. It’s a really soft stone, so you don’t need to work with heavy machinery – just chisels. It feels like carpentry in that way.

Two major surrealist influences of mine are Salvador Dalí and Jean Arp. In Salvador Dalí’s paintings, he elongates and stretches shapes, bodies and concepts like time. I translate these ideas into my own work in a very elemental way. What happens to a circle if you cut it in half, and you stretch it and you pull it in these different directions? Instead of thinking of standard geometrical shapes, you begin to expand your mind and challenge what can be done. That’s how I learned to be imaginative and inventive, by transforming my resources. It helped me understand that there’s the elemental aspect of things and the rest is just intention. What are you willing to do and how far are you willing to question this thing by stretching it? That is how these shapes were born and the underlying idea behind my process.

Can you tell me about how your Ludo board project came to be?

I’m always drawing from enjoyment, play, and beauty to create things that I enjoy making and looking at. I played Ludo as a child – it was the staple board game in my home. Observing how we’ve played Ludo as a society for a long time, I remember asking myself, ‘why can’t this be designed better, or with more intention, as a thing of beauty’? I took a traditional Ludo board and designed it with different patterns and colours recurrent in my work and the objects I collect. I used yellow, green, purple, and a shade that is between orange and red.

I integrated both my art and design practice. Art as a practice is very fluid and you can’t hold this fluidity in a box. Design tells you that there is a box, and you can use it and apply it in different ways. I wanted the consumer to look at my board and think, that looks familiar but I’m not sure what it is I remember.

How does living in Lagos influence your design choices?

Lagos is the place I’ve called home throughout my entire life, and there’s nowhere else I know better. As a designer, it’s impossible to overlook the unique language and aesthetic that defines Lagos. Yes, it may seem chaotic, but there’s an underlying system to this apparent madness. Lagos exudes an energy that propels you into action, even when you least expect it. I deeply appreciate this aspect of the city. When creating LUDO by Yadi my goal was to showcase the remarkable production capacity within Lagos with my partner Opemipo Aikomol. Our central question became: how can we harness this vibrant energy effectively? We set out to collaborate with artisans from diverse backgrounds, channelling their expertise into a simple idea that resonates with everyone.

We are looking at anything we can use here that can be made in abundance, and this way you keep local people employed

Akudo Iheakanwa, designer and founder of Shekudo

Akudo Iheakanwa is an entrepreneur and designer. She is the founder of multiple brands, which produce items such as shoes (under Shekudo), table runners (Oolō), and wellness products (Reclaim). She is a community developer who consistently pushes the boundaries of what her materials and the people around her can do. She relocated from her hometown of Sydney to Lagos in 2017, and launched Reclaim and Oolō, after reimagining Shekudo – a clothing brand she started in Australia – as a footwear brand. Her aim with Shekudo is to empower local artisans, produce with locally sourced materials, and champion handmade craft pieces across the world.

Tell me about Shekudo – what drew you into footwear and traditional craft?

I launched Shekudo as a clothing brand with a friend in Australia, but moved into footwear when I moved to Lagos because I thought it was a beautiful way to combine different elements of our traditional craft, from making heels, to beading, to weavework and embroidery. What drew me into this space was the beauty I saw in the way that Nigerians can build something out of nothing. My dad was the first person to demonstrate this to me – it’s a part of all of us. Unfortunately our leaders haven’t provided us with security we can fall back on, so people have had to work with what they have and create beauty out of the madness.

What are some of the limitations you’ve faced manufacturing in Lagos, and how have you worked through them?

There is a limitation in what materials you can find here. For example, you may find a beautiful leather that you love but there’s only one sheet available as opposed to the ten you need to mass produce the product. The same for heels – it can be so annoying. Often, we use leftover fabrics from designers like Gucci, collected from factories in Italy and Portugal. We bring them over here to sell, and while it is more sustainable, it limits the scale at which you can produce.

We’ve had to find other solutions. What materials can we use that are readily and locally available, which we don’t have to import? I collaborate with local carpenters and artisans to make heels for us.

In terms of fabrics in Nigeria, we have cotton, hand-woven aso oke, adire (a local cotton and dying process), Akwete cloth, and a beautiful silk mix with cotton from the Hausa–Fulani in the north. We recently discovered a handcrafted product made using tangled water hyacinth weeds by MitiMeth. They are dried and turned into ropes that we use to wrap soles and heels and to join tags to our shoes. We are looking at anything we can use here that can be made in abundance, and this way you keep local people employed.

It’s taken me five years to find five shoemakers to work and develop with us in-house. Skekudo is currently in a period of fast growth and we’ve had to partner with a small Portuguese artisanal production company in order to keep up with the number of orders we’ve received from retailers. They have the equipment and systems in place to mass produce the prototypes that we make on ground. Our shoes are made on a table in a room, and that’s about it. We find that the artisans we hire want to be in one room together; they want to work with each other around a table, chat, laugh, connect and look at each other’s work. If I segregate them into their own individual spaces it seems to be quite hard for them and they often make mistakes. In Portugal they have their own individual stations, and each one is responsible for a different part of the process, which is more efficient. Our team can’t do more than 50 pieces in a month and we want to be able to compete on a world stage.

What are your aspirations for Shekudo and the artisans you work with ?

We are trying to push the boundaries of what artisans in Lagos are doing. A lot of them don’t want to try anything different and I have to encourage them and suggest ideas. Sometimes they push back and say it’s not possible or that it doesn’t make sense. But I say everything is possible, and we use our multiple brands and products to encourage them.

For example, we use the same traditional aso oke – a handwoven cloth created by the Yoruba people of West Africa – for our Oolō table runners and Shekudo mules. It blows their minds initially, but they come around in the end. Every day is a compromise and brings change, which can be difficult and tiring but that is the challenge if you want to produce here. I want to keep production in Lagos; it’s hard but it’s worth it. I love seeing what we create here. I love seeing the shock and the confusion too, and I just love the community aspect, the development, that’s my heart. We want everyone to be proud and feel good about what they’re creating, and pass down some of that knowledge and wisdom to someone else.