LA’s Ivan Vasquez on what it means to be Oaxacalifornian

Oaxaca-born chef and restaurateur Ivan Vasquez turned his homesick longings for mole and mezcal into Madre, a family-run franchise in LA. Here, he discusses discrimination, preserving tradition and bringing a community together.

Southern California is home to the largest population of Oaxacans outside of Mexico. Ivan Vasquez is one of them. He arrived in the US in 1996, after one failed attempt to cross the border that resulted in his arrest. He was just 15 years old, and had been working in nightclubs in Oaxaca for two years.

Ivan grew up in a “very poor family” in Oaxaca de Juárez, watching his mother Lucila cook three meals a day to his traditional father’s exacting standards. “She put a lot of time and energy into making traditional dishes like barbacoa and tamales, and she even took pastry classes in the local town,” he says. Despite hardship, Ivan describes these years as “a beautiful experience”, and he named his restaurant, Madre, in her honour. He opened his first location in LA’s Palms in 2015, and further outposts followed in Torrance and West Hollywood. The city’s food culture has long been shaped by immigrants from the southern Mexican state, led by people like Ivan.

“When I was small, I would ask my mother to make estofado mole every week,” Ivan says. “It’s her recipe on the menu today – it doesn’t have the sweetness of other moles, there’s no chocolate. We make it with sesame seeds, parsley, spices, bread and plantains, and serve it with chicken, white rice and pickled jalapenos.”

This is what Ivan calls Oaxacalifornian: a fusion of cultures found almost exclusively in Los Angeles. “Oaxacalifornia is not just about living in California. It’s more about this shared feeling of being away from our motherland, from family,” Ivan says. “It’s a lifestyle. Traditional Mexican food is delicious, and every region is a little bit different. My mum was very good at experimenting, adding a little twist here and there. Her cooking was the first thing I missed when I moved to the US.”

This longing for home is at odds with a longing for more – which is often the impetus for many Mexicans leaving their homes, fleeing conflict or seeking job opportunities. Despite US government programmes over the years (such as the Bracero Program, which issued temporary work permits to millions of Mexicans to ease labour shortages in the wake of the second world war), and consistently recruiting Mexicans in the military, right-wing America has not made it easy to be an immigrant, even today.

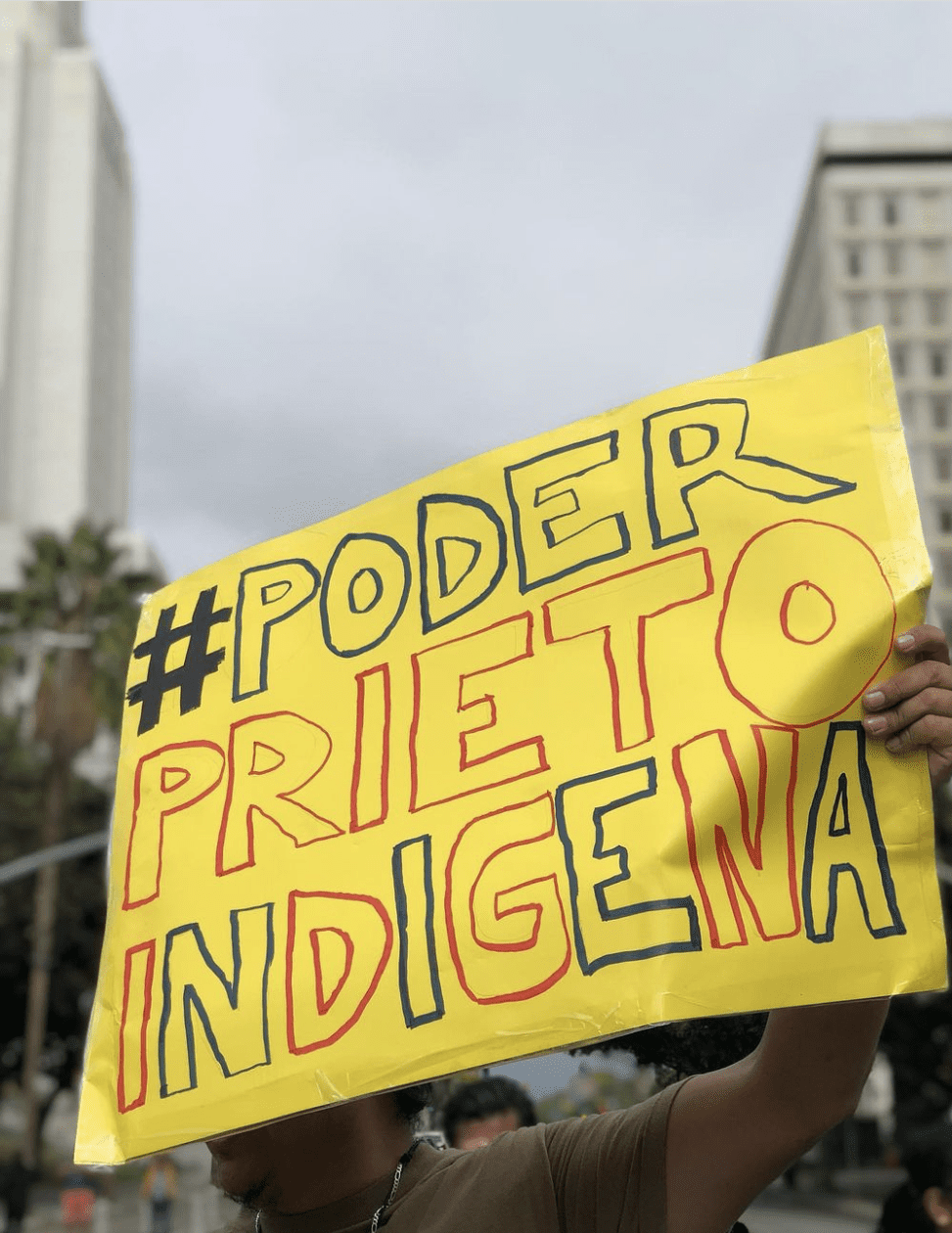

In 2022, audio was leaked in which LA City Council member Nury Martinez made racist remarks about Black and Oaxacan people, describing the latter as “a lot of little, short dark people” and “so ugly”. Ivan tells me that although prejudice against Oaxacans exists even in Mexico, “it always hurts.” Ivan and his community mobilised for a peaceful demonstration outside City Hall, with the help of Odilia Romero, an immigrant rights advocate, and director of social justice organisation Cielo. “It’s important the next generation sees us Oaxacans gathering peacefully against racism. We want to set an example: this is how you generate change and defend your rights,” he says. Others took to disrupting a scheduled city council meeting inside City Hall by chanting their demand: no resignation, no meeting. Martinez announced her resignation hours later.

“We have strong leaders, a strong voice and strong people, including myself,” Ivan says. “I know what it is to struggle. I want those that are in high school right now – kids like me – to know that there is a way to find freedom in this country. I want to motivate them to keep fighting social injustice, to keep trying to create a better future. It’s important for me to play that role in my community – if I was able to do it, you can do it. I’m just waiting for them to do it better than me.”

“We want to set an example – this is how you generate change and defend your rights"

Ivan’s determination to pay it forward comes from both empathy and experience. He understands the power of homesickness and the feeling that one doesn’t belong. His first Christmas in LA was a low point. “I was living with 12 guys in one apartment, and slept on the floor. All I had was 5 USD, so I bought some bolillo bread and that was going to be my dinner. I called my mum, and she was like, ‘Oh, I’m making pozole, tostadas, ponche, tamales’. I started crying, and was like – that’s it. I’m giving up. I’m going back to Oaxaca tomorrow. I was only 16. But the next day, I woke up with a sense of resolve and responsibility, and the guys in my house took me for seafood and a beer. It was the first time I felt some sense of connection to LA. I realised, this is the price you pay to be someone, to make money.”

In Madre, Ivan has not only created a place that plays an important role in Oaxacalifornian life, where community meetings happen and government officials visit, he’s also carved out a space in the city where Angelenos are just as welcome as Oaxacalifornians. A big part of it is the restaurant’s mezcal menu. Getting his liquor licence in 2015 was “magic”, and with more than 500 bottles, he lays claim to the largest private collection of mezcal in the world. An integral part of Oaxacan culture, mezcal is made from the agave plant, often using recipes and traditional techniques passed down from generation to generation (such as Lalocura Mezcal, run by fourth-gen master mezcalero Eduardo Ángeles). “I grew up with mezcal at parties and celebrations. So I took it for granted until I arrived in the US – it’s part of our heritage, it’s in our blood. I have so much admiration for the producers, and how they work.” Currently, Madre hosts five or six sell-out mezcal tastings a year.

Ivan’s grandfather owned a mezcaleria, and he believes the only way to fight what he calls the mass-produced “monster” of mezcal, driven by high demand in Europe and the US, is working closely with small-batch palenqueros. “Mezcalero families in Oaxaca are preserving these traditions, but sadly it’s a dying art, and agave is being exploited. At Madre we try and educate people about how to differentiate between qualities and support good mezcal projects,” he says.

“Mezcal is part of our heritage, it’s in our blood"

I ask Ivan how he drinks his mezcal. Straight? On the rocks? “No ice!” He laughs in horror. “The agave plant takes between nine and 20 years to be harvested, so we don’t want to dilute something that took decades to develop. Every sip is important. You’re drinking history from indigenous communities that preserve this spirit for us to enjoy.”

Like mezcal, Ivan approaches cuisine in a way that honours its craft. One of his favourites at Madre is tlayudas, an unassuming tortilla-based dish that begins ten days before you order it, when the restaurant orders the tortilla from a lady in Oaxaca. “My mum and sister pick up the tlayudas, pack it, ship it, order the quesillo and avocados and black bean paste,” he says. “It all comes together on the plate, but you’d never know the journey it’s been on. It’s the perfect example of Oaxacalifornian.”

Next on Ivan’s agenda is training staff in Zapotec to both preserve the language and allow them to interact more seamlessly with customers from the region. In February, his fourth restaurant will open in the Valencia neighbourhood of Santa Clarita, California, and he has New York and Miami in his sights. For now, though, Ivan is proud of the strength and skills his experience here has brought him. “Bringing the best experience of Oaxaca to Los Angeles satisfies my soul. I’ve brought my ingredients, my mezcal, art exhibitions, and photography, and we’re having really interesting conversations. Madre will continue long after me, this place belongs to the city.”

Explore the ROADBOOK Los Angeles city guide here.