Author Riaz Phillips on why food is the ultimate expression of Caribbean identity

Writer Riaz Phillips shares his recipe for aloo channa curry, and discusses how Caribbean culture and community are fostered through its rich food scene

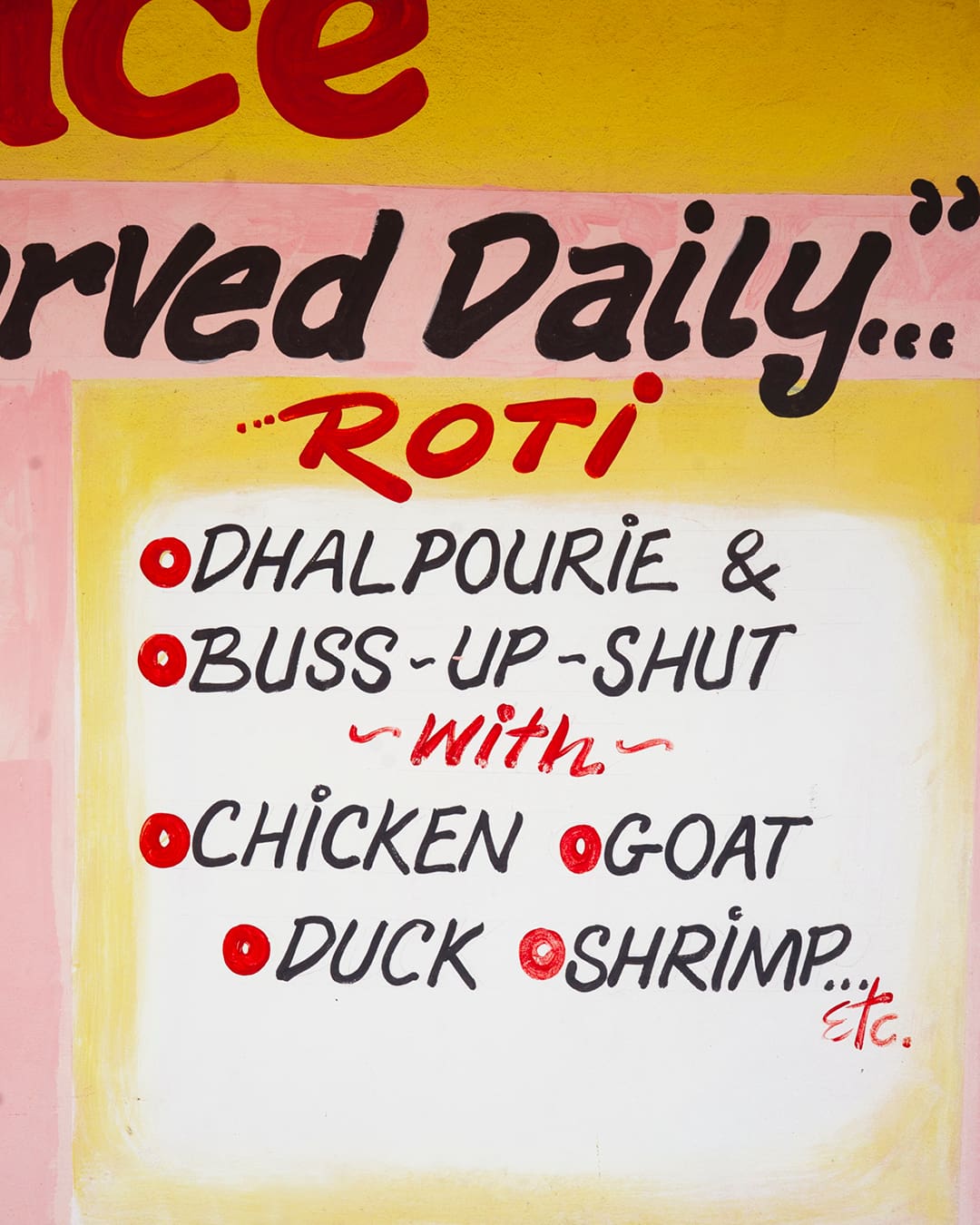

Riaz Phillips is a writer and photographer who was born and raised in London. He is passionate about the Afro-Caribbean food he grew up with, and released his first book Belly Full: Caribbean Food in the UK in 2017, for which he won a Young British Foodie (YBF) Award. His follow up in 2022, West Winds, was awarded the Jane Grigson Award. His third book, East Winds: Recipes, History and Tales from the Hidden Caribbean, published in October 2023, explores the lesser-known eastern corners of the Caribbean, including Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago. The book details recipes for homely spiced stews, bakabana (battered plantain) and creamy, comforting sawine (vermicelli pudding), as well as a whole chapter dedicated to roti. In so doing, the story of this “hidden Caribbean” is revealed, capturing the joy and sense of community fostered by Caribbean cooking.

Here, he shares his recipe for aloo curry, and discusses why food holds the secret to Caribbean identity and its expression.

Where are you from?

For the people who were transported to the Caribbean, not only was their communal identity in limbo, so too was their individual sense of self. West Africans were given first names based on things like physical appearance or at the whim of traders, and their surnames often became those of their plantation owners. It’s how my family had Scottish and English surnames like Bucchan, Simpson, Williams and Phillips without ever having stepped foot in Europe. For those from India, surnames were almost unknown among the lower class who travelled from Uttar Pradesh. In the list of emigrants on the first boat of 1845, printed in the Indian Centenary Review of Trinidad, every single name was without a surname.

It was similar when the Chinese stepped into the Caribbean. When registering upon arrival, the romanisation of names was subject to interpretation by the Western ear and, even with the help of a translator, it was not uncommon for name order to be changed, its spelling to be twisted into familiar pronunciations, hard phonemes to be left out, or even for it to be changed to an English-sounding name. Such transformations can be seen in Guyana and Trinidad where Chinese honorifics such as ‘A’ often became part of the official surname, such as Achong and Sue-A-Quan. In many cases, people acquiesced to these odd derivations to help facilitate their integration.

In addition to names, the other element of identity lost was language. Most of the Amerindian tribes were eradicated by European forces before any substantial accounts of their language could be recorded. The West Africans who arrived in the Caribbean were not uniform and spoke languages such as Akan (from Ghana) and Yoruba (from Nigeria) amongst many more. Colonial overseers forced English on them, which resulted in the Creole “broken” English and patois still spoken today. This marked another erasure of identity as the knowledge of their mother tongue was soon lost. Also, once Indian and Chinese arrivals moved to the settlements, they were funnelled toward and spoke the Creole developed by the Africans who settled there before them.

When you travel anywhere in the Caribbean, if your clothes don’t already give it away, as soon as you open your mouth and utter a word, people know you’re not “from there”. The layers of this run deep. Those of Caribbean descent who travel “back” to West Africa share the same fate, unable to speak Twi, Akan, Yoruba, Igbo and so forth. Not “from there” either. A driver of Indian descent tells of the loss he felt not being able to understand Urdu as his forefathers from Uttar Pradesh did, and how Bollywood DVDs and re-runs on TV with the subtitles turned on helped fill this void.

Likewise, my Uncle Sal tells me how his mother, my Great-aunt Salima, while ethnically Indian, on arrival to Britain felt no kin with the Indians (from India) who she worked with, looked like and lived near, mainly because she was an outcast regarding understanding their subcontinental languages.

The Caribbean and their identity is something I continually discuss. The question ‘where are you from?’ is often wielded toward people of colour in the diaspora, with any answer constantly challenged. People of Caribbean descent, even having given so much to Britain, are rarely accepted as truly being British and no response or act can successfully retort. In the Caribbean, even if you are born in a certain country and have a local accent but moved overseas, you still can be seen as a foreigner and outsider. The one act that cements identity, status and positioning in the Caribbean beyond name and language is cooking. The ability to make a good batch of roti – yes; the ability to professionally wield a karahi to make a curry – yes.

With the ability to make a crowd-pleasing Callaloo or Coconut Bake, I saw even the most cockney of Brits be told they’re “Trini” now. Food again marks itself as one of the most important expressions of identity in the Caribbean. Over the years, for those who wanted to reconnect with their Caribbean heritage, there’s no language to turn to and the erasure of names makes tracing lineage back further more difficult. I found over and over again that when many wanted to reconnect with their heritage, their first port of call was recipes, and hopefully the following recipe can help with that.

Aloo channa curry

Like many of the recipes I share in my book, these dishes are named after their base ingredients. In this case, the names come from South Asian languages such as Urdu, where channa translates as “chickpea” and aloo (or aluk) means “potato”. Though both ingredients feature in a host of other recipes, when you hear a reference to aloo or channa it is most likely their curried forms.

While aloo and channa curries are rarely the stars of the show, they act as a stabilising, reliable force for any meal. Aloo and channa are often served together in a single curry, however, like any successful tag-team or duo, they can perform adequately when separated. Aloo is frequently used to bolster curries be they vegan, meat or fish and when those curries are ladled into a roti it can cause the roti to joyously burst at the brim. Given this, consider what you’re making these dishes for. If you are preparing them for Doubles , omitting the potatoes is most common; for roti you want the potatoes diced smaller but not so small that they completely dissolve into mash. If making curry for dinner or lunch just for you, you can opt for larger potato chunks.

Serves 4-6

Ingredients

1 tbsp curry powder and 1 tbsp

ground cumin (or 1 ½ tbsp madras curry powder)

1 tbsp garam masala

1 tbsp Green Seasoning (see recipe below)

½ –1 Scotch bonnet pepper, deseeded and roughly chopped

6 garlic cloves, roughly chopped

6 tbsp cooking oil of choice

1 small onion, finely chopped

1 spring onion (scallion/green onion), finely chopped

500ml hot water

400g can chickpeas, drained

800g white potatoes, peeled and chopped into bite-sized chunks

Method

In a small bowl, add the curry powder, cumin, garam masala and green seasoning. In a pestle and mortar, mash the Scotch bonnet pepper and garlic and add to the bowl. Add 60ml (4 tablespoons) cold water and stir until the mixture resembles a paste.

In a Dutch pot or heavy-based saucepan, heat the oil over a medium–high heat. When hot, add the onion and spring onion and sauté for 3 minutes. Then add the spice paste and stir for 5 minutes. The paste may begin to stick to the base of your pan; if this happens, add 1 tablespoon of water and stir. Next, add the chickpeas and/or potatoes and stir to combine for 3–5 minutes. If the paste begins to stick to the base of the pan, either add another tablespoon of water or reduce the heat a notch.

Add the hot water and stir. Place the lid on the pan and cook for 25–30 minutes, stirring intermittently every 7 minutes or so to ensure nothing is sticking to the pan. Reduce the heat to low, then remove the lid. The dish is now ready to serve, however, you can leave it to simmer until the gravy is at your desired consistency.

Green seasoning

Makes 800ml

Ingredients

5 spring onions (scallions/green onions), roughly chopped

1 large onion, roughly chopped

1 green bell pepper, deseeded and chopped (optional)

3 ribs of celery (leaves included), chopped

1 Scotch bonnet pepper, deseeded and chopped

2.5cm (1in) piece of fresh root ginger, peeled and finely chopped

8–10 garlic cloves, peeled

1 bunch of parsley (100g/31/2oz)

1 bunch of fresh coriander (cilantro) (80g/3oz)

1 bunch of thyme (15g/1/2oz), leaves picked

1/2 tsp sea salt or all-purpose seasoning

juice of 1/2 lime or lemon (optional)

1 tbsp apple cider vinegar (optional)

1 tbsp light soy sauce (optional)

Method

Wash all the vegetables and herbs, then add to a food processor with 3 tablespoons water and seasoning and blend until smooth. Stir in the citrus juice, vinegar and/or soy sauce, if using. If you don’t have a blender, then finely chop or grate all the ingredients and mash together with a pestle and mortar. Pulse until the sauce reaches your desired consistency and then decant into an airtight jar and store in the fridge. Use within 2 weeks. If you add citric juice and/or vinegar, the mixture should last for up to a month.

If you’re not planning to use the seasoning for a while, you can store it in the freezer and then defrost half a day before use.

East Winds: Recipes, History & Tales from the Hidden Caribbean by Riaz Phillips (25 GBP) is published on October 5